Over at his Lost Tulsa blog, Tom Baddley has posted a great set of photos of Bartlett Square and the Main Mall, prior to their removal over the last few years. (Be sure to notice the photos of the Tulsa Whirled's Main Street facade, a classic example of mid-century Albanian Bunker architecture. They thoughtfully included gun emplacements in the design, which I guess they thought would be useful if the newspaper ever found itself under assault from peasants with pitchforks.)

I thought I'd try to set the Mall in the context of downtown Tulsa's decline, and the various remedies that actually made matters worse.

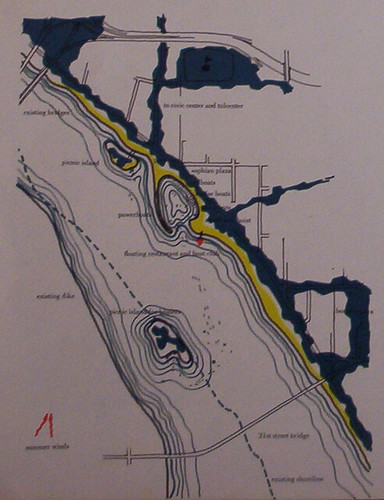

In the late '70s, Tulsa pedestrianized Main Street from 3rd to 6th and Fifth Street from Boston to Boulder, and made 5th from Boulder to Denver a narrow one-lane, one-way street. As usual, just about the time other cities figured out that pedestrian malls didn't work well in the US, Tulsa joined the soon-to-be-passé fad. The idea was to link the two superblock urban renewal developments -- the Civic Center where 5th Street dead-ended at Denver and the Williams Center where Main Street now dead-ended at 3rd Street. The intersection, 5th and Main, became a large water feature, and it was dedicated in memory of U. S. Sen. Dewey Bartlett as Bartlett Square.

Starting in the late '50s with the new County Courthouse, the Civic Center replaced a tree-shaded neighborhood of apartment buildings, retail, and light industrial -- a typical inner-ring neighborhood -- with a desolate, treeless plaza. Particularly controversial was the decision to close 5th Street, which merchants once marketed as "Tulsa's Fifth Avenue." The original plans for the Civic Center featured a round arena, slightly bigger than a city block, which would have required a curve in 5th. When convention facilities were added to the Assembly Center, so that it covered two blocks, 5th Street was to have tunnelled under, but that idea was abandoned over the protests of 5th Street merchants, who feared the loss of business when their drive-by traffic was diverted to 6th and 4th.

The second big superblock was created by blocking off Main Street and Boston Avenue between 3rd and the Frisco tracks. The historic Hotel Tulsa was demolished, along with Tulsa's original commercial district, an area that might have become a quaint, restored district like Denver's Lower Downtown. Instead, it was cleared to make way for the Williams Center: a new hotel, the Performing Arts Center, the Bank of Oklahoma Tower, and the Williams Center Forum, an indoor mall between 1st and 2nd at Main. Main Street, which once linked north of the tracks to south of the tracks, Cain's Ballroom to Boulder Park, once the city's principal commercial street, was cloven in twain.

In order to have a successful pedestrian mall, you have to have pedestrians, so it works best if you pedestrianize areas where there are already a lot of people walking out of necessity. In theory, linking the governmental center to the new "mixed-use development" should have worked well, but the Mall and the superblocks made parking and driving downtown even more inconvenient for people who didn't have to be downtown. Workers might use the Mall, but mostly just during lunch hour. The years following the Mall's completion saw an increased use of telecommunications in business, reducing the need for people to leave their offices during the work day. The Forum was very inconveniently located down a steep flight of stairs a block away from the Main Mall, and ultimately even that path would be blocked when the Williams Center hotel was allowed to expand to the west, into the old Main Street right-of-way.

There was a time when there was a critical mass of workers downtown -- around 70,000 during the last oil boom in the late Seventies. The Mall was popular enough that Tulsa's second UHF station, KGCT 41, tried to build its identity around the Mall. The studios were in the Lerner Shops building, just off of Bartlett Square, and KRMG's John Erling hosted a midday show live from the Mall. (I did a month-long internship at KGCT in May 1981.)

When the office workers went home at the end of the day, the Mall was left to folks with no better place to be. Without enough people living in or near downtown, there was no reason for shops to remain open. Without open shops and auto traffic, there was no natural surveillance -- "eyes on the street" -- and the shady spots that were pleasant places to eat lunch on summer days became places to avoid at night.

(Anyone who was paying attention to what Jane Jacobs was writing as early as 1960 would have predicted this result, but no one was listening to Jane Jacobs.)

Sometime during the Mall years, Downtown Tulsa Unlimited, founded by downtown retailers in the '50s to try to remain competitive with new suburban shopping centers like Utica Square, mutated into an association of office building owners. While there are some sharp staff people at DTU, including DTU president Jim Norton, the folks who call the shots seem to see downtown as an office park -- the "core" between 1st and 6th, Cincinnati and Cheyenne -- surrounded by parking lots for their tenants and other buildings that could be torn down to create even more parking for their tenants.

(Speaking of DTU: They've had a contract with the city to maintain the Main Mall, paid for by an assessment on downtown property. Now that the Main Mall is gone, does the city really need a contract with DTU?)

The pedestrian mall didn't kill downtown retail all by itself, but it mortally wounded what little remained. What really hurt was the depopulation of central Tulsa. Think of a box from Union to the west to Harvard on the east, 21st on the south to Pine on the north -- about 12 square miles. In 1960, the population of that area was about 67,000. That dropped to 50,000 in 1970, 37,000 in 1980, 30,000 in 1990, and increased slightly to about 31,000 in 2000, still less than half the 1960 population. Urban renewal, expressway construction, conversion of land to surface parking to accommodate the new skyscrapers, expansion of institutions like the hospitals and the University of Tulsa, and conversion of residential areas to commercial and industrial uses all contributed to central Tulsa's depopulation. Most of those who remained weren't exactly flush with disposable income. If you don't have rooftops, you won't have retail.

I've got to stop here for now. More about the Mall and its demise tomorrow. Feel free to include your own thoughts, anecdotes, and memories in the comments. Also, feel free to ridicule the Tulsa Whirled's hideous building. (That's it! The building makes me think of the third book in C. S. Lewis's space trilogy: That Hideous Strength.)

To fill the gap, I look at the historical record provided by aerial photos, street directories, and oral histories, all of which reveal that Greenwood was rebuilt after the riot, better than before in the view of many, but it was government action -- in the form of urban renewal and freeway construction -- that produced the empty lots in the '70s which OSU-Tulsa replaced.