The food truck approach to public transit

Many of my hipster urbanist friends are very fond of food trucks. Food trucks today offer a wide variety of cuisines and a wide range of sophistication and price. The mobility of the kitchen allows the restaurant to go where the customer is. Better food can be offered for a lower price because the truck avoids some of the costs that attend a brick-and-mortar eatery. There are no restrooms to clean and stock, no dining room to manage, no tables to clear, no dishes to wash. Cashier and sous-chef duties can be handled by family members; no need to deal with the complexities of being an employer.

The owner/chef can take his skills to where the customers are, and when the customers aren't there, he can park the truck at home and pursue other work. When demand is high, he can run his truck seven days a week. When it's slow, he can shut down for a while without the ticking of the rent clock. Food-truck fans are rightly concerned to protect this innovative approach to food delivery from regulations that seek to eliminate the food truck's competitive advantages under the guise of protecting the public health.

Many of these hipster urbanists are also very concerned about funding cuts for Tulsa Transit, the regional bus service. The system is almost unusable. Every year or so, I take a trip by bus. I'm always frustrated by the long headways (period between buses on a route), long layover times, and limited hours. Only those who have more time than money choose to ride Tulsa Transit. For many, the only alternative is to pay for an expensive taxi ride on the occasions when time matters and friends aren't available to provide a ride.

The solution most frequently proposed is to implement a tax to provide the bus system with a consistent stream of revenue which can pay for more buses, more drivers, and more frequent service. The problem with that approach is that you're going to wind up with excess capacity most of the time, just to ensure that someone can catch a bus on short notice.

What's the most efficient mechanism for allocating supply to demand? The free market, as long as barriers to entry and the allocation of supply are kept to a minimum. Which reminds me of this joke from the Unix fortunes file:

On his first day as a bus driver, Maxey Eckstein handed in receipts of $65. The next day his take was $67. The third day's income was $62. But on the fourth day, Eckstein emptied no less than $283 on the desk before the cashier."Eckstein!" exclaimed the cashier. "This is fantastic. That route never brought in money like this! What happened?"

"Well, after three days on that cockamamie route, I figured business would never improve, so I drove over to Fourteenth Street and worked there. I tell you, that street is a gold mine!"

The absurd element that makes this funny is that everyone knows buses are supposed to follow a fixed route, even though, unlike streetcars, they could be moved to meet demand, even though they never are.

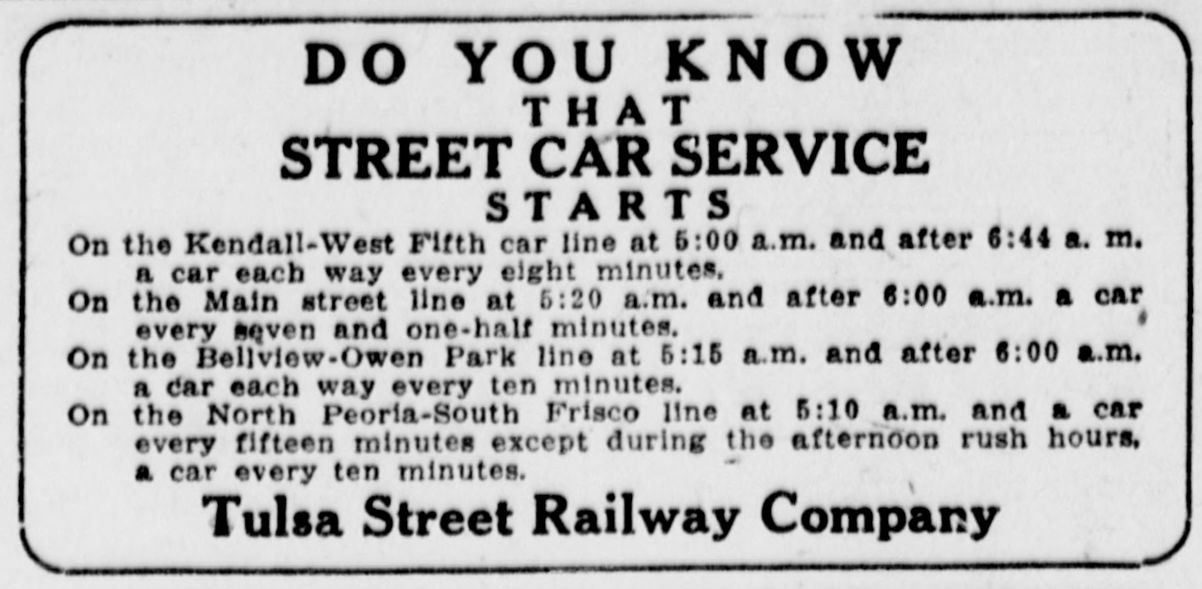

The debate over the regulation of food trucks reminds me of a similar debate 100 years ago. Streetcar companies had been granted franchises by cities to lay track and hang wire on certain streets. The companies made massive capital investments, but they were hamstrung by city regulations and, sometimes, union contracts setting maximum fares and minimum staff levels.

To give you a sense of the struggle between streetcar company and city government, in 1922, the Oklahoma Union Traction company decided to stop running its St. Louis Ave. line to Orcutt Park. The popular amusement park had given way to private development around what we now call Swan Lake. Demand along the line had dropped. OUT wanted to stop running the line but didn't want their competitor, Tulsa Street Railway, to take it over. Presumably the rails and wire had reuse or scrap value as well, so OUT began pulling its infrastructure out of St. Louis Ave., over the objections of the City of Tulsa. The state Corporation Commission, regulator of intrastate rail, was drawn into the dispute.

Early adopters of the private automobile figured out that they could make money toward gas and car payments by driving along streetcar routes ahead of the next trolley and picking up passengers for a nickel (or "jit") each. Passengers liked jitneys because they got where they were going faster and more comfortably than if they waited for the next streetcar. Streetcar companies hated jitneys, because they stole the fares the companies needed to cover their capital investment and fixed costs.

Streetcar companies fought back with political muscle, persuading city councils to pass restrictions and bans on jitneys, bans that persist to this day. The Institute for Justice, which provides pro-bono support for economic liberty cases, worked to overturn Houston's anti-jitney law in 1994:

Santos v. City of Houston. Like Ego Brown, Houston entrepreneur Alfredo Santos discovered an untapped market. A cab driver, Santos discerned a need for a third transportation alternative beyond expensive taxicabs and highly subsidized public buses. He discovered the solution in Mexico City: the "pesero," or in English, the "jitney."Jitneys are a transportation mainstay in large cities around the globe. They run fixed routes and charge a flat fee, like buses. But they pick up and discharge passengers anywhere along the route, like taxis. They are smaller and more efficient than buses and less-expensive than taxis. They also are ideally suited to low-capital entrepreneurship.

Santos began using his cab during off-duty hours as a jitney, operating in low-income Houston neighborhoods. The business was successful, quickly attracting other jitney operators. But the city quickly shut the industry down, invoking its "Anti-Jitney Law of 1924."

In the 1920s, jitneys were the main source of competition to subsidized streetcars. The streetcar companies lobbied in city halls across the country, all but exterminating jitneys. Seventy years later the streetcars are nearly all gone, but the anti-jitney laws remain. Today they are supported by the public transportation monopolies that replaced the streetcars.

Santos challenged the law in federal court, which struck it down as a violation of equal protection and federal antitrust laws. The city did not appeal the ruling, thereby allowing another favorable economic liberty precedent to stand.

(You can read the Santos v. City of Houston jitneydecision online. And here's an article from half a year later about Santos's vision for jitneys, the taxi industry's push for regulation, and support from Houston's transit authority.)

Santos argues that entrepreneurs and the marketplace, not the government, should decide whether there is a demand for jitneys. Santos, 41, has spent more than ten years fighting for jitneys. A cab driver for ten years, Santos had seen jitneys working in Mexico City, where they are called peseros. Wearing a cowboy hat so potential passengers could easily spot him, he would drive East End streets holding out fingers for the number of places available in his cab. Yellow Cab found out about the practice and threatened him with the loss of his cabby's lease if he didn't go back to running his meter as required by law....Santos says jitneys will attract poor people and immigrants who don't own automobiles and are reluctant to call cabs because of the high cost and poor service. Chernow, however, says that about a third of Yellow Cab's trips originate in low-income, minority neighborhoods.

The secret to operating a jitney, Santos says, is to run the route religiously, make lots of quick trips, and develop new customers. Perhaps a driver will occasionally deviate to take a passenger home in a pouring rain, he concedes, or help someone get their groceries to the doorstep. But the driver will need to return quickly to the route to maintain the quality of the service.

Fast-forward 13 years, and a Houston blogger calling himself The Mighty Wizard wonders why jitneys, now legal in Houston, aren't effective in meeting the transit needs of the subject of a news story whose six-mile commute takes 83 minutes by bus.

So why aren't jitneys more widely used in Houston? Well, whenever something is legal but rarely used, the Wizard immediately starts suspecting government interference and sure enough, if one decides to pay a visit to the City of Houston ordinances governing the operation of jitneys (Chapter 46, Article VI), one immediately notices some very serious regulatory barriers to entry that would be jitney operators face in entering the competitive field for transportation.

He spots three barriers to entry and to meeting the needs of customers: The vehicle can't be more than five years old (a standard never used for public transit vehicles or cabs), the driver can't deviate from the route or negotiate price with potential customers (reducing fares might make sense when demand is slack), and a jitney owner must maintain bonding and insurance from which a government operator is exempt.

There are more, but no doubt that the usual rationale would be offered as to why these regulations are in place and that is that we need to protect the public. It should be equally obvious to everyone that this ordinance doesn't protect the public from anything, but was instead written to protect Yellow Cab and Metro from market competition, not to help the citizens of Houston get around more quickly or conveniently.Jitneys also present another problem, this one in the political marketplace. Jitneys don't allow politicians to spend billions of dollars in cost overruns on big transportation make work projects, they don't allow for photo opportunities or to put their names into the history books, nor do they help politicians obtain millions in campaign contributions. They also would drive lovers of government transit berserk. However by lifting lifting the regulatory barriers to entry to jitney operations, the City just might allow a solution to come forward which could allow Mrs. Jenkins to get to her job in 10 minutes and to succeed where taxpayer funded public transit fails.

Way back in 2002, when Tulsa County's "Dialog" process was underway, they sought public input for projects to improve Tulsa County. I offered two proposals: Deregulate jitneys and enable neighborhood conservation districts. Neither idea involved massive construction contracts or revenue bonds, so neither idea went anywhere in the process, which was all about finding popular local projects that could be wrapped around a new arena to get it past the voters.

Before we plow more money into Tulsa Transit and a route model ill-suited to Tulsa's urban layout, why not give private operators a chance to meet the need? They might choose to run a fixed-route without deviation. They may choose a starting point, but the destination and route would be determined by the needs of the current batch of passengers. They might take reservations, like Super Shuttle does with hotels, picking up a series of passengers to deliver them to a common destination.

You may object that the free market may not provide the quality of service needed at an affordable cost. I could imagine churches using their buses and vans as jitneys during the week, with fares reduced to whatever was necessary to cover fuel, if that. Merchants in a shopping center might pool funds to ferry shoppers from home to the store and back. There may be some benefit in a publicly funded "backbone" service -- frequent service along a small number of corridors, to which jitneys would connect.

Transit regulations, like food regulations, should protect the public's health and safety, but otherwise leave the market free for innovation. My hipster friends are excited about taxi alternatives like Uber and don't want to see them entangled in government regulations designed to protect the taxi monopoly. They should be just as excited to unleash a lower-tech, lower-cost means of transportation for the benefit of their less affluent fellow Tulsans.

MORE: An article from the January 2000 issue of The Freeman explains how illegal-but-tolerated jitneys operate in Detroit.

0 TrackBacks

Listed below are links to blogs that reference this entry: The food truck approach to public transit.

TrackBack URL for this entry: https://www.batesline.com/cgi-bin/mt/mt-tb.cgi/7209

Good column.

It has always seemed wrong to me that government (as in New York City) would limit the number of taxicab medallions that it issues. Combined with prosecution of "gypsy" cab operators, this is an absolute legal barrier to competition - an ideal example of regulation to benefit the customer turned upside down, benefiting the business owner instead.

The comparison to food vendors may be a stretch. I don't care whether or not my taxi is licensed. I DO care that my food is safe.

Of course the issue always boils down to: "How much regulation is too much, and how much is enough." There may be a logical reason for regulating taxis, although I can't think of one. But REASONABLE health regulations for food vendors? Definitely!

How to define Graychin's "reasonable"... He does have a point about "Roach coaches".

I have kept for reference another bloggers very-well-reasoned essay regarding public transportation. The link below will take you to a little less humor than Mike's ironical observations, but something (albeit with a bit of math)just as persuasive.

http://www.uwgb.edu/dutchs/PSEUDOSC/MassTransit.HTM

I just finished reading the link provided by Roy. Good stuff. Of special note is something I've been ranting about for years: "Nevertheless, crime is a principal reason why affluent people leave cities. So if you want to revitalize the cities, extirpate street crime (people don't triple bolt their doors against inside traders or crooked lobbyists). Not reduce, not contain, not deter, extirpate it. Eliminate from public discourse any notion that crime is ever justified."

Which is why bucks spent on arenas, river glitz, fairgrounds, ball parks, glass city halls, gifts to American Airlines, massive school bond issues (Criminy! Have we still not attained World Class City status?) ... keeps failing to stop Tulsa's decline.

Since reading your post, I've been thinking about the issues many Oklahomans have been active about recently - food trucks, ecigarettes, ride-sharing, craft brewing, etc - and thinking that many of these people are not your average Tea Party types who are concerned about economic freedom. This is something that has been on my mind lately because I've been trying to think of ways to reach beyond "the choir" of people who tend to be focused on the issue: Tea Partiers, fiscal conservatives, libertarians, etc, & trying to think of ways to connect with people who might not "typically" be motivated to try to do anything about economic freedom. Thank you for showing us all how to think outside the box!

Thanks for the kind words, Rob! An aversion to corporate welfare and an appreciation for small, local business seem to bring left and right together. When people realize that licensing and regulation are often used to block the entry of new competitors for politically favored businesses, the scales fall from their eyes.