Australian election 2016

I recently returned from a business trip to Brisbane, Australia, my first visit south of the equator, and, for the second time in two years, an overseas visit coincided with a general election. Radio, TV, and newspapers were dominated by coverage of the election, but billboard ads and yard signs are rare. (Last March in Israel, political yard signs and billboards were everywhere.)

All 150 seats in the Australian House of Representatives and all 76 seats in the Australian Senate (12 each for the six states, plus 2 each for the two territories) are up for election on July 2, 2016. As in the UK, the party or coalition that controls a majority of the lower house forms the government. The current government is a center-right coalition of the Liberal Party and the National Party which won election in 2013. Tony Abbott, as leader of the Liberals at the 2013 election, became PM, but was ousted last year, just like Margaret Thatcher in 1990, in what the Aussies call a "leadership spill." The new leader of the party and the new PM is Malcolm Turnbull. The principal opposition is the Australian Labor Party, the local manifestation of socialism, and led by Bill Shorten, who took over party leadership after Labor's defeat in 2013. The House serves a maximum three-year term, but the PM can call for a dissolution prior to that time. Ordinarily, half of the 76 senators are elected along with the whole House.

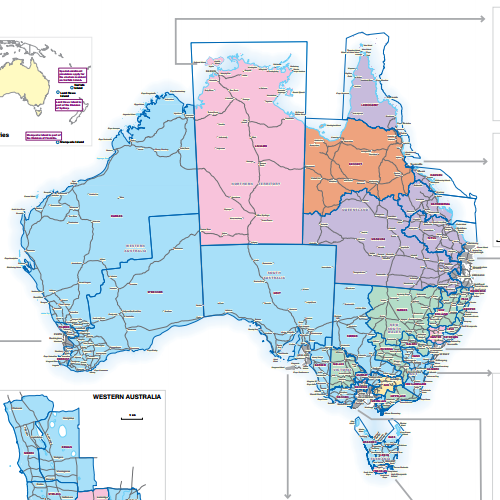

The 150 seats in the House are allocated among the states by population. Within each state, electoral division boundaries are drawn so that each division's population is within 10% plus or minus of the ideal value (population / allocated seats). With a population of 22,793,303, each house member represents about 151,955 constituents. (A U. S. Congressman, on average, represents almost five times as many -- 744,320, as of earlier today.) Even with the smaller population per district, some of the districts are vast. Durack, in Western Australia, is 1,629,858 sq. km., just 5% smaller than Alaska. The smallest division, Grayndler, in the inner suburbs of Sydney, is only 32 sq. km., smaller than Jenks.

This map of the current electoral divisions shows how lopsided Australia's population distribution is: 118 of the 150 divisions are in a swath along the coast between Brisbane and Adelaide. The two most populous states, New South Wales and Victoria, can outvote the rest of the country, with 84 seats in the House between them.

The 2013 results map likewise reveals the lopsidedly urban focus of support for Labor (pink). The ruling center-right Coalition is represented by blue (Liberal Party), green (National Party), purple (Queensland's Liberal National Party, where the two coalition parties have merged), and tan (Northern Territory's Country Liberal Party). Currently, three seats are held by minor parties and two by independents. Representatives are elected using instant runoff voting, so in the rare case where candidates from both the Liberal Party and National Party are on the ballot, supporters of one can give second preference to the other and deny a victory to Labor.

The Senate voting system is strange, and I still haven't got my mind quite wrapped around it. You can vote preferentially for party groups "above the line" or for individual candidates "below the line." I haven't quite grasped how these two types of votes are combined. Preferential ballots are counted using the single transferable vote (STV) system, which produces a proportional result. Consequently, minor parties have a bigger voice in the Senate, where the Coalition currently holds 33 seats, Labor holds 25, the Greens hold 10, five minor parties hold one seat each, and there are three independents. The Coalition needs support from six senators of other parties to get their legislation passed.

And when that doesn't happen -- when the party of government cannot get its legislation through the Senate -- the PM can call for a "double dissolution" in which all senators are up for election. Presumably the new election will either give the ruling party the majorities in needs in both houses or will deliver an unequivocal victory to the Opposition, but either way the logjam will be cleared. A double dissolution requires that some bill has passed the House and been voted down in the Senate twice with at least three months between attempts. Three specific bills involving the construction industry and labor unions were cited by Turnbull in his letter to the Governor-General (Sir Peter Cosgrove, Queen Elizabeth's viceroy in Australia) requesting a double dissolution.

If the newly elected parliament should fail to pass one or more of the bills cited for the double dissolution, the PM can request a joint sitting to consider only those bills, creating a temporary 226-member unicameral legislature, in which the Senate comprises about a third of the total membership. A joint sitting has happened exactly once, in 1974, when Labor sought to enact socialized health care.

You may be heartened to know that an election in Australia is just as susceptible as an American election to turn on some silly non-issue. During my stay, the political world was in an uproar over Labor leader Bill Shorten's remark that mothers handle most of the childcare in the country. This was in connection with his announcement of a US$2.25 billion subsidy for childcare. In response, PM Turnbull and scoffed at Shorten's "sexist" gaffe and pledged allegiance to feminism.

0 TrackBacks

Listed below are links to blogs that reference this entry: Australian election 2016.

TrackBack URL for this entry: https://www.batesline.com/cgi-bin/mt/mt-tb.cgi/7788