Cities: September 2007 Archives

From the Wikipedia entry on Kissimmee, Florida:

The Houston Astros conduct spring training in Kissimmee, at Osceola County Stadium. The Astros' farm system formerly included a Kissimmee entry in the Florida State League. In order to prevent jokes, the team's nickname was the Cobras rather than the Astros.

One evening after all the meetings were over, I decided to visit two towns, one old, one new, south of Orlando's main tourist district.

First stop was Kissimmee. Most people who have been there know the town for US 192, Irlo Bronson Way, a busy strip of tourist businesses that lead to the Maingate area of Walt Disney World. But south of 192 there's an actual town, the county seat of Osceola County, with a main street (Broadway), a courthouse square, an Amtrak station, and a lakefront.

When I was searching for Wi-Fi locations before my trip, I learned that the Kissimmee Utility Authority had established a free Wi-Fi zone in their downtown, so I was curious to see how it was working.

Although Kissimmee's Broadway has some handsome old buildings, plus some new mixed residential and retail buildings being constructed in a classic urban fashion, they all seem to house businesses that are open only in the daytime: banks, real estate offices, a photographer, a guitar store, a Christian book store, antique shops, a bakery, a couple of cafes. Only one restaurant was open, just off of Broadway. I don't imagine a free Wi-Fi zone helps boost downtown business much if the only place to use it is sitting on the curb or behind the wheel of your car. Just to test it out, I did try to connect from inside the minivan, found several of KUA's access points, but none of them strong enough to hold a signal.

The most interesting sight in old Kissimmee is the Monument of States. It has a homemade quality to it that reminds me of Ed Galloway's work near Foyil. It is a 50 foot high pyramid-like structure with rocks from every state embedded in painted concrete, and it dates back to World War II, a project of the Kissimmee All-States Tourist Club. The rock from Oklahoma was a polished slab (quartz, probably) with Gov. Leon Phillips' name engraved in it. It's at the base on the north side, in the lower left of this photo, to the left of the words "MONUMENT OF STATES."

Other inscriptions on the monument appear to have been etched out of the concrete by hand. Here's a vintage postcard of the monument. Here's a fairly recent Flickr photoset. Like our beloved Blue Whale, it was refurbished a few years ago with the help of the good folks at Hampton Inn.

I left Kissimmee and headed to Celebration; more about that in a later entry.

Those are two questions about two major thrusts of the campaign for the proposed Tulsa County sales tax increase for river-related projects. In this week's column in Urban Tulsa Weekly, I ask whether this river tax plan is what we need to do for the sake of Tulsa's children and young adults.

In response to the first question, I deal in passing with one river tax cheerleader's active involvement in destroying a place of fun and happy memories for Tulsa's children, and pass along a suggestion, made by my wife, for how you could protest Bell's eviction from the Tulsa County Fairgrounds, should you decide not to boycott this year's Tulsa State Fair entirely:

In addition to the obvious -- don't spend money on the Murphy Brothers midway -- here's a homemade idea for those who go to the fair but wish to protest Bell's eviction: Wear bells to the fair. You can buy a big bag of jingles at a craft store for a few dollars. Thread a bunch on a ribbon to wear around your neck. Bring extras to give to friends or fellow fairgoers.

And if you want to make the point explicit, stick a nametag on your shirt with the slogan that's been spotted around town: "No Bell's. No fair."

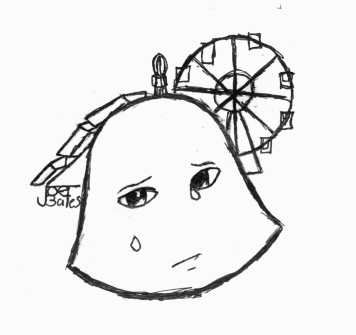

Accompanying that suggestion on page 7 of this week's UTW is the first published work by a budding young cartoonist named Joe Bates, depicting a weeping Bell. He's got some more political cartoons in the work. The demolition of Bell's is something my two older kids saw happening on an almost daily basis, and it saddened them both greatly. I'm proud to see my son express his sentiments so eloquently in art. He's already working on some more cartoons.

Accompanying that suggestion on page 7 of this week's UTW is the first published work by a budding young cartoonist named Joe Bates, depicting a weeping Bell. He's got some more political cartoons in the work. The demolition of Bell's is something my two older kids saw happening on an almost daily basis, and it saddened them both greatly. I'm proud to see my son express his sentiments so eloquently in art. He's already working on some more cartoons.

I mentioned in the column that skipping the fair entirely is hard for a lot of people from Tulsa and the northeastern Oklahoma. Going back to the '40s my great-grandmother and grandmother would enter the craft competitions, and in recent years my two older children have had fun submitting their own creations. Joe has won two blue ribbons, one in 2004 for an acrylic painting and one last year for a convertible built with Legos. Both he and his little sister plan to enter some items again this year. To us, and to a lot of families, the Tulsa State Fair was here before Randi Miller and Clark Brewster and Rick Bjorklund, and it'll be here when they've all moved on to other things. But I can certainly understand those who plan to abandon the fair altogether.

Regarding young professionals, in my column I mention a recent visit to Orlando and a Saturday evening spent on lively Orange Avenue, between Church Street and Washington Street in that city's downtown:

Downtown Orlando has shiny new skyscrapers, a basketball arena, and a beautiful 23-acre lake with a fountain. But I didn't find the crowds around any of those. There were only a few people walking the path around the lake, and the sidewalk along Central Boulevard next to the lake was empty except for me.

Instead, the throng of twenty-somethings was promenading up and down four blocks of Orange Avenue, a street lined with old one-, two-, and three-story commercial buildings. The storefronts of those buildings were in use as bars, cafes, and pizza joints. The same kind of development stretched for a block or two down each side street. There were hot dog stands on every corner. Pedicabs ferried people to and fro. The numbers of partiers only grew larger as the little hand swept past 12.

An observation from that visit that I didn't include in the column: The block of Orange between Pine and Church Streets has these old commercial buildings crowding the sidewalk on the west side and a spacious plaza framed by two modern, round, glass and steel buildings on the east side. Where do you suppose people chose to walk? 90% of the foot traffic stayed next to the old storefronts and avoided the big modern plaza.

This morning on KFAQ, Gwen Freeman and Chris Medlock interviewed real estate expert and urban critic Joel Kotkin. Last week in the Wall Street Journal, Kotkin wrote a pointed takedown of cities that chase the "Creative Class" with civic improvement schemes -- arenas, convention centers, government-planned entertainment districts, light rail, etc. -- while neglecting basic infrastructure and overlooking the concerns of middle-class families. Here are a few key paragraphs:

Governments prefer subsidizing high-profile but marginally effective boondoggles -- light-rail lines, sports stadia, arts or entertainment facilities, luxury hotels and convention centers.Over the past decade, according to a recent Brookings Institution study, public capital spending on convention centers has doubled to $2.4 billion annually; nationwide, 44 new or expanded centers are in planning or under construction. But the evidence is that few such centers make money, and many more lose considerable funds. The big convention business is not growing while the surplus space is increasing. New sports centers add little to the overall economy.

Critically, misguided investments shift funds that could finance essential basic infrastructure. Pittsburgh has spent over $1 billion this decade on sports stadia, a new convention center and other dubious structures. Heralded as major job creators and sources of downtown revitalization, they have done little to prevent the region's long-term population loss and continued economic stagnation. Much the same can be said of Milwaukee's new Santiago Calatrava-designed Art Museum, or Cleveland's Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Transportation priorities are also skewed. Government officials in Minnesota spent mightily on a light-rail system that last year averaged barely 30,000 boardings daily. It did not focus nearly as much on overstressed highway bridges, or the bus systems serving the bulk of its mostly poor and minority transit riders. Most other light-rail systems, built in cities with highly dispersed employment, also have minuscule ridership, but consume a disproportionate share of transit funds that might go to more cost-efficient systems, including bus-based rapid transit.

In this morning's interview on KFAQ, Kotkin expanded on this theme. Here's a link to the MP3 file for the hour containing the Joel Kotkin interview. He packed a lot of important ideas about cities into a very short segment. I'll try to unpack some of them before too long, but two that come to mind:

- The fact that downtowns were designed for commerce, not for residential living, but close-in neighborhoods were designed well for housing, while providing a customer base for downtown businesses. My response: Tulsa tried to save its downtown by destroying or amputating major sections of its close-in neighborhoods to make way for parking and freeways and to eliminate "blight". (Of course, the blighted homes and apartment buildings were not much different from those in now-valued neighborhoods like Brookside and Swan Lake.) Now we're trying to undo the damage by converting commercial buildings with residential space, something I've supported, although Chris Medlock pointed out that we've spent a lot of public money per person added to the downtown population.

- The importance of parks in every neighborhood, not just a handful of centrally-located showplace parks. I need to transcribe exactly what he said, because it was spot on -- something about having to "make a day of it" to visit one of these showplaces, rather than being able to integrate a neighborhood park into your everyday life. Every neighborhood needs its gathering places, whether that's a park or a playground or a coffee house.

There's also an interview with Kotkin on townhall.com, conducted by Bill Steigerwald, about the continued importance of manufacturing to the economies of American cities. Steigerwald is a Pittsburgh native, so it's natural that the conversation would focus on the departure of heavy industry and billions spent on stadiums, light rail, and other pretty things at the expense of basic government services.

Increasingly it's the Sunbelt where manufacturing is sought and celebrated, not the old Rust Belt, which views its history with the same kind of "cultural cringe" that fashionable Tulsans feel about cowboys, Indians, and oil:

I have to tell you, almost every place I go in this country, particularly where the economy is growing, if you ask business people what is it that would really help them, they say "skills." Machinists. Welders. It's not like there's a Ph. D. shortage, generally speaking. But there is a welder shortage, there's a plumber shortage, there's a machinist shortage. But nobody wants to talk about this. Cities that have lost their industrial base don't want to talk about it, and many cities that still have it are almost ashamed of it. In one of the great historical ironies, the places where they are not ashamed of manufacturing are places like Houston and Charleston and Charlotte. But the places with the great industrial traditions, it's almost as if they are ashamed of their lineage.

Kotkin makes some great points about how manufacturing brings outside money into a city (our Chamber of Commerce seems to believe that only conventions and tourism are capable of doing that), and how people forget about skilled labor jobs:

Everyone talks about how we're becoming a society of low-end service workers and high-end information workers. But here's something in between -- basically the logistics and manufacturing industry -- and nobody seems to be focused on it.

What can governments do to attract this sort of business? The basics:

I would say infrastructure and training are the two big things -- and if you think of the training as part of the infrastructure, it's really one thing. You need roads that go in and out. You need modern industrial space. You need reliable electricity. You need shipping facilities. You need workers who are relatively skilled, trainable and reliable. It's really not rocket science that you can do that and that would promote the manufacturing sector of the economy.

And to retain and rebuild a city's manufacturing base?

Are there companies that would like to expand? Are there companies that want to stay? Ask them what they want.

But that isn't what cities are doing:

We live in this dream world where we say, "Well, if we have a fancy stadium with sky boxes, that will keep businesses here." Well, what do you mean by businesses? Do you mean the gauleiters who represent multinational corporations, so they can hang out at a fancy football game? Or are we talking about somebody who's got 15 people working for him in a shop somewhere in the suburbs and would like to get to 30? What are his issues? Are they tax issues? Are they training issues? Are they regulatory issues? You've got to go ask! I don't see anyone interested in that anymore. It's all "What does some 23-year-old, footloose student want? Does he have enough jazz clubs to go to?" Or some footloose 50-year-old corporate henchman. "Does he have enough arts facilities?"As a country, we're kind of delusional about our economies. I've found a few places in the country where they focus on this stuff, but I'm kind of becoming a persona non grata for raising these issues. I'm not raising them as a conservative, saying we shouldn't have taxes or shouldn't have regulations. I'm just saying, "How do you provide for a broad-based economic opportunity for your people? Isn't that what's it about?" Unfortunately, for most mayors in America, that's not what's it's about. What it's about is, "How do I keep the public employees happy? How do I keep the people at the very top of society happy? And how do I put on a good enough show so that everybody thinks I have a hip, cool city."

The conversation between Kotkin and Steigerwald ends with the role of local papers in pushing these projects of questionable value:

[Kotkin:] I'll tell you the truth, a lot of the blame comes to the journalists. The journalists never ask the tough questions. They basically follow the scripts that they are given. And also part of the problem, and we've talked about this in general about journalism these days, you have got a bunch of young kids who are there for two or three years. They don't understand what crap this is. To them it's all, "Well, there's an art museum downtown. That'll be good for me." If there is some "starkitect" -designed building, they say, "Wow, that's sort of fun for me." They don't care.[Steigerwald:] I've always said the newspapers of America should be indicted en masse for having countenanced 50 or 60 years of the destruction of cities. I bet 95 percent of newspapers have applauded and cheered every boondoggle, every urban-renewal project back in the 1950s, every new light-rail project -- no matter what it was, newspapers cheered them on.

[Kotkin:] And what happens if you have the temerity to suggest that this may not be the way to go? You're "anti-city," you're "pro-suburbs," you're a "neoconservative" -- like I'm Dick Cheney or something. You get name-called. And all you're saying is, "Look, are we sure that what we are putting our money into is really what matters, given the tremendous pressing needs that every city has?"