Cities: June 2009 Archives

Notes about demolition and neglect, here and elsewhere:

From the Beryl Ford Collection/Rotary Club of Tulsa, Tulsa City-County Library and Tulsa Historical Society.

Red Fork's oldest remaining high school building is to be demolished. The 1925 building served for most of its history as Clinton Middle School, but when first built it was the high school for the Red Fork district, which was previously located on the Park Elementary campus, which dates back to 1908. (The Park high school was built in 1918, according to the Sanborn map, but has been gone for decades.) Clinton continued as a high school until 1938, when Daniel Webster High School opened. This story tells about the time capsule discovered in its cornerstone:

When officials took down the cornerstone, they found a copper box not much bigger than a car stereo in a gap in the brick wall.In it, they found a small U.S. flag with 48 stars, several yellowed copies of The Tulsa Tribune newspaper, and lists of members of the Order of the Eastern Star, Red Fork Masons, Red Fork school board members and faculty and staff members at Clinton, which was a high school in 1925.

The Tulsa Public Schools website has a slide show and high resolution images of some of the objects in the Clinton Middle School cornerstone.

The first time I found my way onto W. 41st Street many years ago, I was impressed and amazed by the civic buildings along this half-mile stretch between Union Ave. and Southwest Blvd:Trinity Baptist Church, Pleasant Porter School (originally Clinton Public Grade School), sited in a shady grove of tall trees, Clinton Middle School, and the Clinton Memorial First Baptist Church of Red Fork -- each had a certain dignity that marked Red Fork not as a suburb, but as a town in its own right. The old Baptist Church was demolished to make way for the new Clinton Middle School; now the old school is being torn down after 84 years of service.

(Here's some more historical information on the Clinton family and the school that stood on their old homestead.)

Four miles north-northeast, someone has taken photos of the interior of the Tulsa Club building, on the northwest corner of 5th and Cincinnati. The art deco building has been left to rot, unsecured, by its current owner, and it has become the target of graffiti vandals who seem to know that no one cares. I've been in the building twice: Once for the school prom ("Dutchman Weekend") my sophomore year in high school, and once just after the Tulsa Club shut down for good and the fixtures were auctioned off. There are hints of what once was, but the interior is pretty well trashed.

On to Detroit, where the last vestiges of old Tiger Stadium, aka Briggs Stadium, are being demolished for no good reason. The infield stands still stood, and preservationists had been working successfully to raise funds to preserve them, maintain the diamond as a community ball field, and use the stadium structure as a museum to house broadcaster Ernie Harwell's collection of memorabilia. Despite the progress of preservationists in raising funds, the Detroit City Council decided to turn even more of their once-bustling city into flat nothingness.

Neil de Mause explains what made Tiger Stadium special and worth saving:

Tiger Stadium is now the last surviving example of an old-style upper deck overhang. Yankee Stadium will be gone shortly; Fenway Park doesn't have an upper deck to speak of; and Wrigley Field, for all its charms, has a top deck set way back from the action. That leaves the sliver of stands still standing in Detroit as the only place in the world where baseball fans will be able to experience what was once commonplace: cheap seats that, thanks the miracle of cantilevering and the willingness to make some field-level patrons sit in the shade, are closer to the field of play than all but the priciest field-level seats at modern stadia -- stunningly close at Tiger, where Tom Boswell famously wrote that sitting in the upper deck behind home plate and watching Jack Morris pitch enabled him to truly learn the importance of changing speeds.

I saw a game there once. In 1988, my last full summer of bachelorhood, my friend Rick Koontz and I went on a week-long "Rust Belt Tour" that took us to Wrigley Field, Comiskey Park (the original one), Tiger Stadium, Cleveland Municipal Stadium ("the mistake by the lake"), and Riverfront Stadium. 21 years later, only Wrigley still stands. We had great seats to watch the Tigers play the Yankees, a game the Tigers won, 7-6 in the bottom of the ninth, a six-run inning that concluded with an Allan Trammell grand slam home run. It was the most exciting game of the trip, and a great place to watch a game. (It was also the night the Pistons lost to the Lakers in Game 7 of the NBA finals. We were relieved, given Detroit's reputation for violent celebrations.)

National Trust for Historic Preservation president Richard Moe writes of Tiger Stadium:

Demolishing the stadium is a mistake. Even in its diminished, partly demolished state, the stadium served as a defining feature of the historic Corktown neighborhood-a reminder of better days, but also a cornerstone for future revitalization of the community. Redevelopment of this iconic historic place for, among other things, youth baseball leagues, could transform it back into the thriving center of community activity that it once was. Now, city leaders have chosen a course that will in all likelihood lead to yet another empty lot in Detroit-the last thing the city needs.

More from the National Trust for Historic Preservation on Tiger Stadium's demolition:

Despite a protest at Tiger Stadium last week, Detroit contractors began razing the 1923 structure the following day. Late Friday afternoon, a judge issued a temporary restraining order, which should have halted all destruction, but crews continued demolition until the end of the day.On Monday Wayne County Circuit Judge Prentis Edwards lifted the restraining order and rejected the conservancy's request for the injunction.

"[Demolition crews] were out there an hour after the decision. They didn't waste any time," says Michael Kirk, vice president of the Old Tiger Stadium Conservancy, which requested a permanent injunction to halt the demolition. "We don't understand it. There's no other development deal pending for the site, so the need for speed doesn't make any sense."

City attorneys argued that the conservancy could not raise enough for the $27 million construction project to retain Navin Field, the oldest part of the existing stadium complex.

Plans to demolish the remaining section of the old stadium were set back in motion after a 7-1 vote on Tuesday, June 2, by the board of Detroit's Economic Development Corporation. Waymon Guillebreaux, executive vice president, said in a statement last week that the Old Tiger Stadium Conservancy "is still far short of its targets" agreed upon in a memorandum of understanding with the city that was signed last fall and claimed the conservancy did not have "secure commitments for funding the project."

The board acted despite $3.8 million earmarked by Sen. Carl Levin (D-Mich.) for the Old Tiger Stadium Conservancy's plan; an identified $19 million from new market, "brownfield," and state and federal historic tax credits (some of which were already applied for and approved); and $500,000 in grants, loans and private donations.

Lowell Boileau, a painter, created a website in the late '90s called The Fabulous Ruins of Detroit, a site that contains hundreds of images of abandoned and now-demolished buildings, including abandoned suburban buildings that took the place of previously abandoned urban buildings.

Zimbabwe, El Tajin, Athens, Rome: Now, as for centuries, tourists behold those ruins with awe and wonder. Yet today, a vast and history laden ruin site passes unnoticed, even despised, into oblivion.Come, travel with me, as I guide you on a tour through the fabulous and vanishing ruins of my beloved Detroit.

It's a tour worth taking -- well-organized with an "express" path that hits the highlights, and "detours" that allow deeper exploration.

Sadly, at a time when mainstream public support for historic preservation is growing, the National Trust for Historic Preservation has decided to squander its hard-won credibility by turning its blog over to the promotion of "gay pride" during the month of June, in a series of posts that have nothing to do with preserving and protecting historic buildings. (One exception: There is a post about preservation in West Hollywood; the "gay" connection is that it was written by a preservationist drag queen.) The latest example is this essay on "gayborhoods" entitled "Pardon Me Sir, But Can I Queer Your Space." This is a classic example of a venerable organization being hijacked to serve someone's personal agenda rather than the cause for which it was founded.

More linkage, less thinkage, until I get out from under the pile:

Abandoned Oklahoma is a website devoted to photography of abandoned places around the state. Homes, industrial sites, parks, schools, churches. Sites include the Labadie Mansion in Copan (north of Bartlesville), the Santa Fe Depot in Cushing, the Page-Woodson School in Oklahoma City, the Hissom Memorial Center near Sand Springs. The photos are fascinating, often poignant.

A similar site, Underground Ozarks, has several pages devoted to Monte Ne, southeast of Rogers, Ark.

The abandoned million-dollar resort known as Monte Ne was the dream of former Liberty Party presidential candidate William Hope "Coin" Harvey. In 1901, the eccentric Harvey purchased 320 acres near Rogers, Arkansas to become a health resort, political headquarters, and place for civilization to arise after the apocalypse (which Harvey believed was imminent). The resort had two massive hotels, an enclosed plunge bath, a golf course, and gondolas to ferry visitors across the lagoon. In later years, Harvey even added a Roman amphitheater, which is now submerged under Beaver Lake.

Russell Johnson has much more information about Monte Ne and Coin Harvey.

And now for a deliberate, man-made ruin:

(This really deserves an entry of its own, but for now I just want you to see the link.)

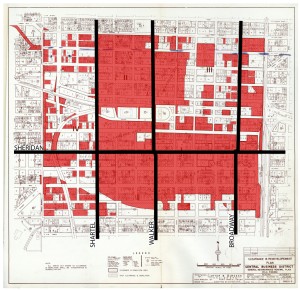

Blair Humphreys is getting caught up on his blogging, and the most dramatic thing he's posted is this map of the Oklahoma City urban renewal plan. The map, created in 1965 by MIT-trained architect I. M. Pei and Carter & Burgess, defined the areas of downtown to be cleared and redeveloped according to the Pei plan. Blair has shaded the map to highlight the doomed zones. It's nearly everything from NW 6th to SW 3rd, from Western Ave. to the Santa Fe tracks. (Bricktown, east of the tracks, was spared.) Click through to see a much larger image and to read Blair's comments.

Blair Humphreys is getting caught up on his blogging, and the most dramatic thing he's posted is this map of the Oklahoma City urban renewal plan. The map, created in 1965 by MIT-trained architect I. M. Pei and Carter & Burgess, defined the areas of downtown to be cleared and redeveloped according to the Pei plan. Blair has shaded the map to highlight the doomed zones. It's nearly everything from NW 6th to SW 3rd, from Western Ave. to the Santa Fe tracks. (Bricktown, east of the tracks, was spared.) Click through to see a much larger image and to read Blair's comments.

Blair notes that "old plans can tell us a lot about how the city came to be the way it is." He has scans of many important Oklahoma City plans and hopes to put them all online in the future.