Cities: April 2010 Archives

Wichita has a downtown grocery store.

I came across it while out for a walk in the eastern part of downtown, near the recently opened Intrust Arena. (Some people go to the Y or the hotel exercise room. I walk through downtowns and historic neighborhoods.)

The store would be easy to miss. It's in an old two-story building, a block off of Douglas, the main east-west thoroughfare through downtown, across the street from the city bus terminal. It's also close to the newly opened Intrust Arena, and as a result it came close to not being there at all.

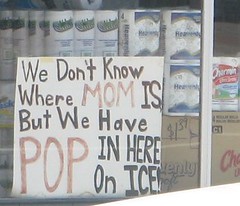

Ray Sales Co.'s sign announces retail and wholesale groceries. The retail part is a small storefront (maybe 20x20) that offers a selection of basic food and home necessities, more variety than you'd find in a convenience store. It's just a block away from the historic Eaton Hotel, which has been restored and converted to residential use, and just a few blocks more from the lofts in the warehouses of Old Town and downtown office buildings that city officials hope to redevelop as residences.

I stopped in for a bottle of Diet Coke and spoke briefly to the lady behind the counter. In response to my comment about the arena being nearby, she told me that the county had wanted the land for the arena development, but preservationists had identified the building as historic, which prevented the building from being knocked down and the store from being displaced from its home for 36 years.

I stopped in for a bottle of Diet Coke and spoke briefly to the lady behind the counter. In response to my comment about the arena being nearby, she told me that the county had wanted the land for the arena development, but preservationists had identified the building as historic, which prevented the building from being knocked down and the store from being displaced from its home for 36 years.

While I was in the store, I witnessed the kind of personal service that small, family-owned businesses are renowned for. Customers from all walks of life were treated with kindness and respect, with extra assistance for those who needed it.

Had it not been for the historical status of the Ray Sales building and the Eagle Hall Building next door, the county would have bought and demolished the buildings, and it likely would have been the end of the line for the small business, at least as a downtown grocery. It would have been hard for the grocery to find another affordable location nearby. Its customers -- downtown residents and workers, bus riders passing through the station -- would have lost a valuable resource. You're not going to find a box of marble cake mix or a 55 cent can of pop at the Intrust Arena concession stand, which isn't even open most days.

Had it not been for the historical status of the Ray Sales building and the Eagle Hall Building next door, the county would have bought and demolished the buildings, and it likely would have been the end of the line for the small business, at least as a downtown grocery. It would have been hard for the grocery to find another affordable location nearby. Its customers -- downtown residents and workers, bus riders passing through the station -- would have lost a valuable resource. You're not going to find a box of marble cake mix or a 55 cent can of pop at the Intrust Arena concession stand, which isn't even open most days.

Tulsa saw this happen with the Denver Grill, one of Tulsa's oldest restaurants, and the Children's Day Nursery, founded in 1916, which were both demolished to make way for the BOk Center, even though the arena could have been situated to leave those two buildings, at opposite corners of the site, in place. The Denver Grill relocated to the once-and-future Holiday Inn at 7th and Boulder, but the move from a corner diner to the second-floor of a hotel cost it visibility and customers, and it's no longer in business. The Children's Day Nursery, providing convenient day care near the civic center and the city bus terminal, no longer appears to be in business anywhere.

It amazed me that historic preservation laws in Kansas were sturdy enough to stop a local government from taking land for a publicly owned facility, so I did some research.

In 1977, while Tulsa leaders were still busily demolishing historic buildings and neighborhoods in the name of progress, the Kansas Preservation Act became law, declaring that "the historical, architectural, archeological and cultural heritage of Kansas is an important asset of the state and that its preservation and maintenance should be among the highest priorities of government."

Every government action involving land -- whether a city or county's own project, or government approval for a private project (e.g. building permit, zoning change) -- within 500 feet of a place on the National or Kansas Register of Historic Places is subject to review by the State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO). If the SHPO finds that the project will encroach upon or damage historic property, the project can't go forward unless the local government determines, "based on a consideration of all relevant factors, that there is no feasible and prudent alternative to the proposal and that the program includes all possible planning to minimize harm to such property resulting from such use." Kansas courts have construed this requirement strictly: A city council can't just say, "we determine," and the project moves ahead. "Alternatives may not be rejected unless they present 'unique problems' or 'cost or community disruption' of 'extraordinary magnitudes.'"

The results are evident all over Wichita and on small town Main Streets across Kansas. While Wichita joined the urban renewal orgy of the '60s -- the scars are most apparent a few blocks north of Douglas and between Main and the Arkansas River -- the bleeding was largely stopped when the bill passed, and the kind of urban fabric that Tulsa lost long ago is still present in Wichita.

But the difference is not just one of laws. Kansas could pass a strict historic preservation law because Kansas leaders see the value of preservation. There is a presumption in Kansas in favor of preservation, a presumption that isn't widely held among Tulsa leaders. I wouldn't expect to see the sentiments expressed by the Wichita Eagle editorial board, in a November 15, 2006, editorial, expressed in our daily paper:

Some destruction of the old is unavoidable if Wichita wants to make way for new growth. But public officials also must make sure that these buildings - and their owners - get a fair hearing....Board members properly start from an assumption that old buildings are worth preserving....

Two buildings on the site stand out as worthy of preservation: The Ray Sales building at 206 S. Emporia and the Dancers Building at 200 S. Emporia. The county should try to find a way to incorporate them into the master plan. They're not directly in the arena footprint. And they have architectural character and charm that would help provide a visual link to the brick-and-gaslight feel of Old Town.

As this process goes forward, arena stakeholders must work to find the right balance between preservation and growth.

There will be tough decisions.Wherever possible, though, let's preserve downtown's history and character.

In city after city, state after state, preservation only caught on once local leaders with wealth and social influence (often, as in Savannah and San Antonio, the wives of prominent businessmen) adopted it as a cause. For whatever reason, that still hasn't happened in Tulsa.

MORE: Here's the section of the Kansas State Historical Society's website on the Kansas Preservation Act. Their guide to the Preservation Act has a good summary of the history of the law and how it is applied.

A 1977 documentary on historic preservation in Oklahoma has been posted online at the I. M. Pei Project website. The half-hour film, entitled "Born Again: Historic Preservation in Oklahoma," is narrated by Norman architect Arn Henderson.

It opens with a sequence of demolitions of beautiful and historic office blocks in downtown Oklahoma City. Cynthia Emrick of the National Trust for Historic Preservation notes the conflict set up by the Federal Government in 1949, chartering the National Trust to "preserve the nation's heritage as expressed in the built environment" and at the same time green-lighting federal funding for "urban renewal."

Next up is James B. White, head of OKC's Urban Renewal Authority. White expresses the hope that by entering the program at a later date than most cities, OKC will learn some lessons avoid some of the mistakes other cities made. Oops.

White's comments embody the attitude of apathy towards preservation that ruled Oklahoma in the 1970s:

We are a new country. We are a new state. When you're talking about one generation almost from its beginning, I get my self a little lost with the terminology of being historical. I may be right, I may be wrong. I think most of what we have revolves around the terminology of nostalgia. I don't think that we can really call it historical at this particular time in our particular programs in the buildings that we have encountered....I think our eastern states have more things that are historical. Certainly things like Mt. Vernon, the buildings in our capital that go back a couple of hundred years. But we haven't even reached the century mark in our state yet, so I just don't know what is historical and what is not. I don't put myself up as an authority.

Emrick provides the obvious rebuttal:

If you're going to create something with age and glory, then you have to give it a chance to age.

The film moves next to Oklahoma City's Heritage Hills neighborhood in the late 1960s and the effort to protect it with a historic preservation ordinance. Howard Meredith, State Director of Historic Preservation, argues that a historical survey, a preservation ordinance, and a review commission are essential to effective preservation.

Mr. and Mrs. L. G. Ashley talk about the historic landmark designation of Boley, one of Oklahoma's distinctive black-founded towns, established just before statehood by Creek freedmen.

A segment on Tulsa mentions the preservation of old City Hall at 4th and Cincinnati by private owners and has brief glimpses of three Bruce Goff masterpieces: The Page Warehouse on 13th St (now demolished), the Riverside Studio (Spotlight Theater), and Boston Avenue Methodist Church, whose members invested hundreds of thousands of dollars in restoration and in an addition that harmonizes with the original building's architecture.

The last segment of the program focuses on Guthrie, Oklahoma's, territorial and original State Capital. In 1977, city leaders were only beginning to appreciate the economic benefits of historic preservation:

We have two choices, one is just let it rot, another choice is to tear it down and start building back, and I don't think that's going to happen.... I think we're going to recognize the heritage that we're stewards of here.... We absolutely must have some sort of zoning for this district that will help us preserve the buildings.

The film is itself a type of historic preservation, capturing attitudes, fashions, and hairstyles from the mid '70s.

Here's a direct link to Part 1 of Born Again: Historic Preservation in Oklahoma on YouTube.

The I. M. Pei OKC project is an interesting exercise in preservation itself, devoted to presenting artifacts relating to the master plan that demolished hundreds of historic buildings in downtown Oklahoma City. MIT-trained architect I. M. Pei was commissioned in 1964 by the Urban Action Foundation to develop a plan to modernize downtown. You can see the results in the Myriad Convention Center (Cox Business Center), the Myriad Gardens, Stage Center (Mummers Theater), and numerous parking garages and plazas. A 10' x 12' scale model of downtown as it would look after the plan's completion in 1989 (the city's centennial) was prepared to help inspire citizens to approve the plan. That model has been restored and will be unveiled on Monday at the Cox Business Center.

The website includes maps of the Pei Plan, images of downtown before urban renewal, and video resources, including a film called "A Tale of Two Cities" which was used to promote public acceptance of urban renewal by Oklahoma Citians. There's an excellent synopsis of urban renewal in Oklahoma and how it was used not only in the big cities, but also in places like McAlester, Edmond, and Tahlequah. (It neglects to mention, however, the use of urban renewal to clear most of the Greenwood District.)

A well-written comment on the website by Scott Bryon Williams is worth repeating here:

Unfortunate that even OKC was not spared the utopian, yet disastrous hand of modern city planning of the sixties, robbing countless American cities of their hard-earned history and identity. What a true loss of visual design variety in the built environment.Urban renewal and the Eisenhower highway program have been the most devastating events to established residential neighborhoods, commercial districts, and urban cores leading to the growth of an unsustainable suburbia and barren, depopulated city streets.

I.M. Pei's OKC urban planning concept model is truly a time capsule demonstrating the short-sighted and ill-conceived visions for America's cities' futures. In the historical photo archive, compare the richness and wealth of the former downtown with the fractured, patchwork of today.

Subsequent generations have and are recognizing the mistake of large scale demolition and investing trillions of dollars to rebuild and recreate vibrant, healthy urban environments. It is unfortunate that America lost so much of its wonderful history within such a short period to euphoric ignorance. Equally unfortunate is that this attitude still exists among most of the public with the irrevocable destruction of historic structures and neighborhoods.

Let the I.M. Pei model be a learning tool of our mistakes of the past.

Cato Institute senior fellow Randal O'Toole will speak in Tulsa on Saturday, April 24, 2010, 1:30 p.m., on the topic of comprehensive planning. The talk is sponsored by Oklahomans for Sovereignty and Free Enterprise (OK-SAFE) and will be held at the Hardesty Library, 8316 E. 93rd St. The event is free and open to the public. Here's their blurb about the event:

Heard a Lot Lately About:A Tulsa Without Cars...A Light Rail System...

New Urbanism...MAPS 3 and PlaniTulsa...Wondered What it's All About?

Randal O'Toole, senior fellow with the Cato Institute and author of The Best-Laid Plans: How Government Planning Harms Your Quality of Life, Your Pocketbook, and Your Future and Gridlock: Why We're Stuck in Traffic and What to Do About It, discusses how government attempts to do long-range, comprehensive planning inevitably do more harm than good by choking American cities with congestion, making housing markets more unaffordable, and sending the cost of government infrastructure skyrocketing. Does this effect how, and whether, churches are built?

O'Toole will also speak in Oklahoma City on Monday, April 26, 2010, at 6:30 pm at the Character First Center, 520 W. Main.

While I disagree with OK-SAFE's opposition to PLANiTULSA, I respect the fact that it is grounded in principle. (That's in contrast to groups who are trying to derail or mutilate Tulsa's first comprehensive plan in a generation in order to serve their own institutional and commercial self-interests.) It's certainly reasonable to be skeptical about large scale, long-range government planning. A good deal of the sprawl and urban destruction of the past fifty years was the product of a previous generation of government planning. And the places that urbanophiles hold most dear were built before zoning and planning took hold of our cities.

It should be said, however, that developers of that era had a sense of self-restraint -- think of the long-standing gentleman's agreement that no building in Philadelphia would be taller than the William Penn statue atop City Hall. And the way development was financed in that earlier era encouraged permanence. Typically, you were building for yourself, not building something to flip as quickly as possible. At some point construction shifted from being a craft performed as a service and turned into a commodity-producing industry.

As Paul Harvey used to say, self-government won't work without self-discipline.

I would urge OK-SAFE members to look at the PLANiTULSA documents, what they actually say, as opposed to what someone calling himself a new urbanist said on a website somewhere. What they'll find, I think, is something very different from the large-scale, overly-prescriptive comprehensive plans of the '50s and '60s. They won't find anything calling for a "Tulsa Without Cars." Existing single-family residential developments are labeled as Areas of Stability (much to the chagrin of the development industry). If implemented, PLANiTULSA would allow for types of development that are currently very hard to do under our existing zoning code. Parking requirements would be reduced, so you wouldn't need to buy as much land to put up a commercial building.

As long as you have people living in close proximity, you're going to need rules, since what I do with my property affects my neighbor's enjoyment of his. As long as local government is involved in building and maintaining streets, water lines, and sewer lines and providing police and fire protection, local government is going to need to be involved in urban planning. The question then becomes whether your planning process and philosophy reflects your city's values and an accurate understanding of how people interact with the built environment.