Oklahoma City Category

A friend posted an item on Facebook celebrating 14 years of Oklahoma City being a "big league city," praising those who voted to tax the Oklahoma City citizens on the necessities of life for the benefit of billionaire team owners and their millionaire employees.

It was so nice of the voters to help out so that the millionaires and billionaires didn't have to cut into their profit margin to have a place for their entertainment business.

The friend who posted this is a conservative and someone I agree with on 90%+ of issues. He likened the subsidy for Oklahoma City's basketball arena ("infrastructure investments") to tax cuts as having positive, trickle-down economic impact.

Emotions seem to overwhelm logic, data, and common sense when it comes to professional sports subsidies. I believe in limited government that does what government only can do. Tax cuts let people keep the money they've earned and use it for their own priorities. Subsidized sports facilities take money away from people (using a regressive sales tax) to funnel it into a small number of already stuffed pockets in the name of civic pride. It's the sort of subsidy conservatives condemn were it going to any other industry.

The original big-league cities became big-league by having a sufficiently large and prosperous population to provide a market for team owners to hire the most talented players and coaches and to build great places to watch an entertaining spectacle. Ballgames were just another entertainment option alongside amusement parks, dances, concerts, plays, and movies, and the promoters in all of those entertainment fields were responsible for the cost of building and operating their facilities.

Private businessmen built magnificent stadia and arenas for their sports entertainment businesses -- Fenway Park, old Yankee Stadium, Ebbets Field, the Forum in Inglewood, Wrigley Field, Tiger Stadium, to name just a few -- until cities showed a willingness to throw money at them for the ego boost of having a team. That launched an taxpayer-funded, ever-escalating spiral where teams play off sucker cities against each other, threatening to move as a way of extorting more taxpayer subsidies rather than reinvesting their own profits into their entertainment businesses.

Sports-team owners and the consultants they hire argue that the taxpayer funds invested in sports venues produce a return on investment by economic development and resulting growth in tax revenues. But economic analyses have shown again and again that taxpayers never recoup their "investment." The teams don't generate enough new economic activity to generate additional tax revenue to match the tax dollars that were spent to build, renovated, and operate the venue. If cities want to increase the amount of money available to pave streets and fight crime, they'd do better to put their tax dollars directly to those purposes rather than spend it on sports venues.

The Field of Schemes website maintains a chronicle of the intercity arms race over stadium subsidies and regularly highlights retrospective studies of actual economic impact vs. forecasts. Neil deMause, the site's publisher and author of a book by the same title, recently called attention to a study of the economic impact of the new Atlanta Braves stadium in Cobb County, Georgia.

J.C. Bradbury, the Kennesaw State University sports economist who was appointed to the Cobb County Development Authority in 2019, has written several studies of the Atlanta Braves stadium that have been noted here, including one on how commercial property values around the stadium went down relative to nearby areas, one on how sales-tax receipts for Cobb County went up less after the stadium opened than did sales-tax receipts in neighboring counties, and one on how property values overall in Cobb County did not rise relative to neighboring counties following the stadium's opening. Now, for the fifth anniversary of the stadium's opening, Bradbury has done a comprehensive study of the development history of the Braves stadium and its costs and benefits, and let's cut to the big takeaway:The fiscal benefits of Cobb funding Truist Park fall well short of its cost to taxpayers, who are left to fund an annual revenue shortfall of nearly $15 million, which translates to approximately $50 per Cobb household per year.

I didn't copy the many links that are embedded in that text -- click through to the article and you'll find links to data backing up each of those statements. Here's a direct link to the latest study by Kennesaw State.

Another recent article shows that the absence of Major League Baseball spring training doesn't seem to harm spring training cities in Arizona and Florida. Spring training in 1995, affected by the ongoing 1994 baseball strike, saw dramatic declines in attendance but no corresponding effect on sales tax and hotel tax revenues. It seems that plenty of people want to go to Arizona and Florida in late February and March, baseball or no baseball -- something to do with the weather.

Oklahoma Sen. James Lankford has twice filed a bill, co-sponsored by Democrat New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker, in 2017 and 2019, to close the loophole that provides a federal tax break for government bonds that finance sports venues, and another bill on the same subject (but with different sponsors) was filed last month. DeMause notes that closing the bonds loophole would have an impact, but it still wouldn't end the sports subsidy arms race. The best way to kill that, he says, is to make all subsidies benefiting private corporations taxable income, an idea that was proposed in Congress in 1999:

SUMMARY: Distorting Subsidies Limitation Act of 1999 - Amends the Internal Revenue Code to impose an excise tax on any person engaged in a trade or business who derives any benefit from any targeted subsidy provided by a State or local government. Defines such a subsidy as one which is designed to encourage a business to locate or remain in a particular jurisdiction. Denies a tax exemption for any interest earned on bonds which provide such subsidies. Prohibits the use of Federal funds to provide such a subsidy.

This goes well beyond sports, and it would benefit all cities and states if they no longer felt compelled to provide direct subsidies -- rather than good infrastructure, public safety, competent and efficient government, and low taxes -- to lure businesses to relocate.

It also seems strange for conservatives to celebrate subsidizing a team in the NBA -- a league that couldn't back away fast enough from a mild criticism by a team general manager of the Chinese Communist Party's repression of Hong Kong. The NBA's online store wouldn't allow fans to order custom gear with the phrase Free Hong Kong on it, classifying it as a "hateful message." Megan Kelly's interview with NBA owner Marc Cuban laid bare the league's callous and unprincipled pursuit of CCP cash. ESPN exposed abuse occurring in the NBA's Chinese training camps. The NBA also uses its cultural clout to promote sexual confusion and perversion and other destructive leftist causes. Why would any Oklahoma conservative want to put more money in the NBA's pockets?

I guess OKC got an ego boost out of having a team in one major league sport, but the rest of the world looks at the Thunder as an odd case of a major league team ending up in a minor league city, sort of like the Green Bay Packers.

Spaghetti Warehouse, one of the catalysts for transforming a neglected neighborhood of warehouses into Oklahoma City's Bricktown entertainment district, closed its doors today after 26 years of business, a victim of the surrounding district's success. The restaurant opened for business, with space for 425 diners, on November 12, 1989, at 101 E. Sheridan Ave.

Of all today's news, this story may seem minor, but it touches on the hidden history of the revival of America's downtowns through adaptive reuse of older buildings. In the urban renewal orgy of the 1950s and 1960s, main streets took a beating. Downtown promoters, facing competition from new car-friendly shopping in the suburbs, thought the solution was to mimic the suburbs: demolish older commercial buildings and close streets, replacing them with modern shopping malls and acres of parking.

As Jane Jacobs wrote in The Death and Life of Great American Cities, "Old ideas can sometimes use new buildings. New ideas must use old buildings." (Click the quote to read more of the context.) Warehouses and industrial buildings, at the periphery of the central business district, were often overlooked by the urban renewal wreckers, and so they became the raw material for the visionaries of urban revival.

The first Spaghetti Warehouse opened in a forgotten corner of downtown Dallas in 1972. Eclectic decor (including a dining room inside a restored streetcar) in an unusual setting drew diners, and a patented steam-cooking method for pasta fed them quickly and kept them coming back. Over the next decade, the restaurant's success inspired other entrepreneurs to renovate nearby buildings for clubs and eateries. The result was Dallas's West End entertainment district.

The concept expanded to 14 locations when it opened in Oklahoma City. That same month the Bricktown Association was formed and city planners began looking at how to manage increased interest in the area. Piggy's BBQ and the Pyramid Club had already been operating in the area, and another nightclub opened that December.

Renovation and promotion of Bricktown as an entertainment district had begun in 1982. The opening of the OKC Spaghetti Warehouse in 1989 pre-dated the MAPS vote by four years and the completion of Bricktown's canal, ballpark, and arena by almost a decade.

I reached out to BLD Brands Director of Marketing Kathy Wan with a few questions about the Oklahoma City closing and the fate of the Tulsa store in the Bob Wills District, which opened in July 1992. She assured me, "We are definitely not closing Tulsa!"

So what was the problem in Oklahoma City? Ms. Wan explained:

We are closing due to two main reasons - business at this location not doing as well as before and we want to introduce a new look of Spaghetti Warehouse. Parking is definitely an issue at OKC because we have a lot of families and large groups as patrons. Economic and demographic dynamics of downtown warehouse districts have changed over the years so we need to update our branding and strategic plans. We are working on plans to reopen in the OKC market. We do not know yet if this particular location still makes sense for the new SWRI brand so this is something we are evaluating very closely in the next several months.

Tulsa's location has its own off-street lot. There are off-street lots near the OKC location, but not immediately adjacent, and these lots serve dozens of nearby restaurants and clubs. That makes the location less than desirable for the kinds of large groups that a restaurant of that size needs to attract.

Here is the press release from the parent company, as posted by KFOR:

After more than 30 years in the community, we have made the difficult business decision to suspend operations and announce the closure of the Spaghetti Warehouse Restaurant in Oklahoma City.The closure is effective on Tuesday, February 2nd. We are working closely with everyone on our staff, whose hard work and dedication is appreciated and we thank them for their many contributions.

To our many guests, we say thank you. We enjoyed serving you, your family and friends. And, it was our pleasure to share in the celebrations that took place over countless lunches and dinners, not to mention birthdays, anniversaries and other special occasions.

Spaghetti Warehouse was one of the first businesses involved in the Bricktown revitalization and we thank everyone in the Oklahoma City community who we've served and who supported us. For anyone who has a question about our restaurant in Oklahoma City, we invite you to send us an email at: info@meatballs.com.

As we continue to work on a new look for our brand, we are hopeful that in the near future we can reopen Spaghetti Warehouse within the Oklahoma City market.

MORE: Steve Lackmayer of the Oklahoman has more about Bricktown's history and recent attempts to make a deal to develop the unused upper floors of the Spaghetti Warehouse building.

SOMEWHAT RELATED: Excerpts from an insightful article by the late Jane Jacobs on how cities can enlist time and change as allies in the struggle to keep neighborhoods vital. She deals with the particular challenges of immigrant-dominated neighborhoods, the need for "community hearths," and the problems wrought by gentrification. This epitomizes so much of what is lovely in her urban criticism -- carefully observing reality and then finding and encouraging patterns that work because they are aligned with human nature. Too much of 20th century urban development was using bulldozers and billions of dollars to extinguish urban life where it naturally sprang up and then to try to recreate it artificially somewhere else. Urban Husbandry (a term coined by Roberta Brandes Gratz to describe a non-hubristic approach to city planning) finds naturally occurring signs of city life and, like a farmer, prunes, weeds, waters, and fertilizes to help the natural growth along -- a less expensive and more effective approach to Big Project Planning.

Some interesting observations about the people of Oklahoma City and the memorial they created and maintain, from NYU media, culture, and communication professor Marita Sturken in her 2007 Duke University Press book Tourists of History: Memory, Kitsch, and Consumerism from Oklahoma City to Ground Zero.

One of the primary ways that individuals are encouraged to interact at the memorial is through the fence that is now placed on an outside wall at its entrance. This was the same fence where people initially left objects. The designers had envisioned three small sections of fence in the children's area that would encourage a similar activity, arguing that the fence itself was not as important as "what the fence allows to happen." Yet several family members were concerned that this fence, which had been so important to them in those first years, would be lost, even though a few felt it was an "immature" form of memorial. When the memorial was completed, the fence was transported by volunteers to an outside wall, where it is both separate from and part of an entry into the memorial. The material on the fence is only a fraction of the massive inventory of objects that the memorial has acquired and which are part of its archive.In its incorporation into the memorial design, the fence remains a primary site where people come to leave objects and messages. There are much-considered rules concerning this activity and these objects, which reflect the overall thoughtfulness and intensity of the memorial's intended rituals. Objects that are left on the fence are allowed to stay for a maximum of thirty days. The memorial staff then removes them if they are not related to a particular victim or agency and according to issues of space and durability. The memorial staff will not place something at the fence if someone sends it in; it must be placed there in person. Rules are different for the chairs, where items are left for seventy-two hours after an anniversary ceremony and otherwise removed and discarded after twenty-four hours (though the staff will, on request, move an object then to the fence). This policy was the result of an extended debate among families, survivors, and rescue workers because many survivors and rescuers thought that it would look tacky to have objects left on the chairs.

The Memorial Center, which opened In February 2001, now houses a massive and growing collection of materials in its archive. According to the archivist Jane Thomas, once people realized that their collection was "more than 3,000 teddy bears," they began to send in other materials: photographs, documents, artwork, and personal material from families; trial materials; and documents, such as surveys, from the process of writing the mission statement of the memorial. The archive has six areas of collection: the history of the site; the incident itself, including rescue and recovery; responses to the event, including media coverage; the investigation and trial; spinoffs, such as new regulations and laws that resulted; and memorialization. It now houses over eight hundred thousand pieces, including documents related to the McVeigh and Nichols trials, seventy thousand photographs, newspaper articles, and over one hundred thousand objects, such as cards, letters, quilts, art objects, uniforms, memorial designs, the personal effects of some victims, reporters' notes, shattered glass from the building, and items from the building such as the playhouse from the day care center's play yard....

The memorial design thus encourages many different kinds of responses, encompassing as it does a broad range of spaces, each with particular intent. Visitors are encouraged to be active in responding to the memorial, by leaving objects on the fence or drawing things in the children's area. People often depart from the proscribed codes in interacting with the memorial, for instance, dipping their hands into the water in order to leave handprints on the bronze gates. The memorial is open all the time and is a place that people often wander through at night. It is staffed constantly by volunteers, many of whom are survivors. Many family members and survivors work as docents for the Memorial Center and are frequent visitors to it. It has what is often referred to as a fervent volunteer culture, with seventy-five volunteers working every week.

The memorial is thus integrated into the community of Oklahoma City in complex ways that are about integrating a difficult past into the everyday. This intense community involvement is a factor in the relationship of the memorial to the National Park Service, which is in charge of the rangers and brochures at the site. According to the memorial's executive director, Kari Watkins, the Memorial Foundation restructured its relationship to the NPS in 2005. The NPS, says Watkins. expected the local community to recede as it has at other, similar sites, but the community in Oklahoma City is too invested to fully hand over the site. Thus, as in the design of the memorial, the local community has consistently made clear, both emotionally and financially, its ownership of this memorial site. This incorporation of the memorial into the city has been facilitated by the sense of community and local pride that is a part of the memorial, and its pedagogical mission, one that is fervently expressed and dedicatedly carried out, and that centers in many ways on an embrace of citizenship and civic life.

Steve Lackmeyer has a story in today's Oklahoman about the dilemma facing Oklahoma City as surface parking downtown is being replaced with new development.

Now, [Stage Center] is set to be torn down to make way for a tower rising at least 20 stories into the skyline. And if one is to consider carefully the comments made Thursday by Mayor Mick Cornett, this won't be the last demolition sought to make way for a new tower....The old home of Carpenter Square theater on the southwest corner of Main and Hudson features a beautiful colored mosaic tile facade. Originally the home of Bishop's Department Store decades ago, one can dream up the restoration of the building's jewel box glass storefront displays where the plywood now stands.

That building, a vintage mid-rise "auto hotel" garage and other early to mid-20th century buildings on the block may be next on the list of buildings to be torn down to make way for yet another tower.

Oklahoma City, which recoiled after the Urban Renewal demolition spree in the 1970s, has had relatively few downtown preservation battles since the MAPS-fueled revival began in 1993.

Empty land, scars remaining from unfulfilled dreams of the earlier Urban Renewal era, was plentiful 20 years ago. But that surplus of land has been depleted thanks to hundreds of millions of dollars invested downtown this past decade.

The skyline wants to grow. Oklahoma City must now decide what older buildings must go to accommodate that demand.

It's a nice problem to have, for land to be more valuable to develop than to use as surface parking, but Oklahoma City should think carefully before sacrificing more of he remnant of its early 20th century downtown urban fabric to make way for new steel and glass erections.

Some points to consider:

The pre-World War II buildings that may be sacrificed for new skyscrapers were built to pedestrian scale. Even pre-war high-rises tended to be built with a retail-friendly first floor. (Even the Empire State Building, tallest in the world when it was built, has ground floor retail.) New skyscrapers tend to be monotonous, with first floors that are undifferentiated from the rest of the building on the exterior and little more than elevator lobbies on the inside. At the very least, design guidelines could require a retail-friendly, pedestrian-friendly ground floor in new buildings.

Skyscrapers will increase downtown employment, which will increase demand for parking, which could lead to the sacrifice of still more low-rise, pre-war buildings for surface parking. Tulsa saw this happen in our 1970s building boom. Combined with and enabled by urban renewal, it turned our downtown from a mixture of uses into little more than an office park, dead after dark. The daytime employees will want places to eat lunch, but they won't be around to keep retailers open in the evening, and the skyscrapers and their attendant parking will eliminate older buildings that could house uses to generate 24/7 activity. While skyscrapers may draw new residents into the center city, plenty of those new downtown workers are quite happy with their single-family suburban homes, and they'll want a place to park. Planners should do the math for proposed new skyscrapers: Number of new workers minus number of workers likely to live within walking distance (or to commute via mass transit) equals the number of parking spaces that should be required to be incorporated into the building.

There's a real danger of replacing diverse building stock with the equivalent of a monoculture, which is as vulnerable to disease and disaster in the built environment as it is in the natural environment. Development is somewhat at the mercy of investment fads. If everyone sees office space as a good investment, they're going to build, build, build until office space is overbuilt, driving out buildings suitable for other uses in the process.

Historic preservation played a key role in Oklahoma City's urban revival. MAPS investments had impact because they were placed in and near areas like Bricktown, Civic Plaza, and West Main that had been untouched by urban renewal, and, in the case of Bricktown, already had pioneer investors working to redevelop them.

In the 1980s, Oklahoma City, perhaps in reaction to the orgy of demolition in the previous two decades, adopted urban design guidelines, neighborhood conservation districts, and historic preservation districts for both commercial and residential areas. When the boom began in the 1990s, many protections were already in place, and others were added, no doubt with less friction because precedents for such protections had already been set. Then-Mayor Kirk Humphreys told a Tulsa Now tour group in 2002 that design guidelines were the city's way of protecting the taxpayers' massive investment in downtown. Tulsa's developers and their allies have blocked adoption of similar measures here.

In the comments to Lackmeyer's story, I pointed to Paris for a way to give the skyscraper builders some room to play while protecting the remaining diversity and history of the downtown core.

Paris made the decision to protect its historic core from high-rise redevelopment. Skyscraper development was diverted to an industrial area called La Défense, about three miles west of the Arc de Triomphe, along the same axis that connects that monument to the Louvre via the Champs Elysée. The official website for La Défense describes the area before the transformation:

Apart from its strategic location on the historical axis extending from the Champs-Elysées, there was little indication that the La Défense Roundabout would one day be home to the future business district. Dilapidated houses and small factories for the engineering and automotive industries were bordered by shantytowns and the occasional farm.

The name of the place comes from an 1883 monument at the center of that roundabout, commemorating the defense of Paris during the 1870 Franco-Prussian War. The area was identified as a location for new urban development in 1931, and major construction (delayed by depression and war) began in 1958 with CNIT, a large exhibition center, followed by several waves of high-rise development.

La D&efense, looking east along Paris's historic axis toward the Arc de Triomphe

The 400-acre district now accommodates 38 million square feet of office space, 150,000 employees, 20,000 residents, and 2.3 million sq. ft. of retail (including continental Europe's largest mall, at 1.3 million sq. ft.). Beginning in 1970, it was connected to the rest of Paris by express rapid transit (RER line A) and since 1992 also by Métro Line 1. (Note that even in urban, densely developed Paris, this district still experiences a daily influx of at least 130,000 commuters and can only house about 13% of its workers.)

Oklahoma City could choose to do something similar: Encourage new skyscraper development in an underused area without historic significance near downtown and link it to the core by transit. To my outsider's eye, the industrial area along Reno between Western and Penn, west of downtown, and along Reno between I-235 and I-35, east of downtown, both look like good possibilities for this sort of place. Oklahoma City could improve on Paris's example by ensuring that such a skyscraper district is pedestrian-friendly and has a cohesive urban fabric, not a mere collection of isolated starchitect sculptures.

MORE:

Habitats for Humans: A Skyscraper Is Not a Sculpture: An essay contrasting the way earlier skyscrapers were designed to fit into the urban context and newer skyscrapers are designed as standalone monuments to their architects. The essayist points to New York's early 20th century rules for skyscrapers as the antidote:

We inherited some pretty wonderful skyscrapers from the years before previous global economic disasters: the Metropolitan Life Building (1909) The Empire State Building (1931), The Chrysler Building (1930). These older towers left an incredible urban legacy and it is easy to agrue that they represent the perfection of the urban skyscraper. They are successful at every scale: from a distance they are soaring and beautiful landmarks, global icons of the city and symbols of success and possibility. As part of a street their bases widened to fill their blocks, responding to the height and rhythms of neighbouring buildings, creating a real urban density. Up close, their frontages are richly detailed and animated by shops and entrances, just like those of any generous and lively urban building....The majority of recent towers are very different and their form follows from a very different function: To be seductive CGI sculptures in promotional material, to distance occupants from the 'dangers' of the city, and to compete with other tall neighbours. The city context of many skyscrapers has become irrelevant with the consequence that new skyscrapers, as opposed to being a crescendo of urbanity, are now actively destructive to their urban contexts.

Skyscrapers are no longer designed to contribute to the creation of the great human habitat - the city....

On a recent trip to Madrid I visited the Cuatro Torres development. This was the city's prime new office district consisting of four, starchitect designed towers in vast open spaces. The city stopped at the edge of the development; human activity died away, street life disappeared, the wind whipped up and the towers loomed large as in the architect's dream. If we are trusting architects and developers to build our cities then we should expect more like this.

The answer to this problem is to once again consider the skyscraper as part of its urban context; the habitat of the person on foot.

We need to insist that the form of new skyscrapers follow an additional urban function: to enliven the city at every scale, particularly the one that is currently ignored - the scale of the person walking on the street. The Architect's vanity, and developer ignorance that demands that their sculptural artwork should be realised, uncompromised by such restriction, must be challenged....

Our skyscraper designers could do worse than look again at the rules that led to some of the best urban skyscrapers ever built - The 1916 New York Zoning Resolution. It aimed to ensure that these great urban crescendos were as generous as possible to the pedestrian environment below, and the city as a whole.

Looking at the successful results, a series of rules of thumb can be distilled: At ground level, a more urban result is achieved when the tower's base fills its plot. Here, vibrant, streets are more likely when sides of this of the base animate their surroundings with shop units or entrances to apartments above. The height of this section should create a good enclosure of the street without creating a dark chasm. Above this level the building steps back to the tower - this prevents downdraughts and allows light to the street. The tower element will generally rise above, creating a dramatic form on the skyline (complementing rather than clashing with neighbours). Simple.

The 1920 Robelin map of Paris shows La Défense as a mere suburban roundabout.

La Défense official website (English version)

Jillian Haswell's brief history of La Défense, with photos and a description of new development planned for the near future.

La Défense: From Axial Hierarchy to Field Condition, a 2011 essay by Nick Roberts of Woodbury University on the urban design history of the district. The abstract:

Paris La Défense, the largest dedicated business center in Europe, originated in utopian schemes of the early 20th century, and developed rapidly in the immediate post-war years. As corporate structures and the needs of office design shifted, however, the monumentality and utopian formalism of the 1950's master plan failed to accommodate the needs of capital. As the project developed in the 1970's, it shifted into an open and flexible field condition supported by intense networks of transportation, energy and information.Using the writings of Shadrach Woods and Alison Smithson as references, the essay discusses the shift in design thinking that took place in the late 1960's, as the project evolved from a Beaux-Arts inspired sculptural composition to the open and flexible infrastructure that has allowed La Défense to continue its steady growth despite the recent economic downturn.

I emailed FOP political consultant Victor Ajlouny and requested a copy of the FOP's press releases on their poll and their endorsements. The eight-page Tulsa FOP poll release featured a question about the impact that an endorsement from the Tulsa Metro Chamber's political action committee (TulsaBizPac) would have on a voter's decision -- would it make a voter inclined to support or oppose a candidate, or have no impact?

| Support |

5% |

| Oppose |

51% |

| No impact |

38% |

| Unsure/refused |

6% |

The poll by Strategy Research Institute was of 500 high or moderate propensity Tulsa voters, distributed across the city (at least 50 from each council district). No word on the partisan breakdown. A sample of 500 yields a margin of error of 4.4% at a 95% confidence level.

As a reminder, here are the endorsements and contributions announced a week ago by the Tulsa Metro Chamber's PAC, TulsaBizPac:

Endorsement in both primary/general elections and financial support

Jack Henderson (D), District 1 ($2,500)

David Patrick (D), District 3 ($2,500)

Phil Lakin (R), District 8 ($2,500)

G.T. Bynum (R), District 9 ($2,500)Endorsement and contribution primary only

Jeannie Cue (R), District 2 ($2,500)

Ken Brune (D), District ($1,000)

Tom Mansur (R), District 7 ($2,500)Financial support ONLY

Blake Ewing (R), District 4 ($1,000)

Liz Hunt (R), District 4 ($1,000)

Chris Trail (R), District 5 ($2,500)

Karen Gilbert (R), District 5 ($2,500

Byron "Skip" Steele (R), District 6 ($2,500)

The full text of the FOP poll question about the Chamber PAC:

Question 14.0 Similar to what took place earlier this year in Oklahoma City's Chamber of Commerce...the newly created Tulsa Metro Chamber of Commerce, Political Action Committee, has built a HUGE War Chest intended to influence, indeed CONTROL, the outcome of the 2011 election cycle in Tulsa. Part of this effort involves the Chamber's Political Action Committee donating large sums of money to candidates, as well as funding their own campaigns in support of, or opposing, candidates of choice through independent expenditures. Would learning this through a trusted source make you inclined to: Support a candidate who is endorsed by the Tulsa Chamber of Commerce and/or who accepted large amounts of funding from the Chamber's Political Action Committee, or; Oppose a candidate who is endorsed by the Tulsa Chamber of Commerce and/or who accepted large amounts of funding from the Chamber's Political Action Committee, or; Would this knowledge have NO IMPACT on your decision to SUPPORT or OPPOSE?

While this might be considered a "push poll" question, it demonstrates how voters will respond if the issue is framed for them in this way, using an accurate description of what happened earlier this year in the Oklahoma City elections and the apparent similarity of the Tulsa Metro Chamber's involvement in the Tulsa city elections. This is very bad news for the Tulsa Metro Chamber's future as a preferred vendor to the City of Tulsa and for the political future of the candidates their PAC endorsed or funded (an endorsement in all but name).

It's noteworthy that the story in the Tulsa World covering this poll did not report this result. They also omitted the results that showed 62% preferring four year council terms (staggered to every two years) to the current 3, 74% preferring 12-year term limits for all city officials, and 70% giving Mayor Dewey Bartlett Jr mediocre to failing grade. (32% gave him a mediocre C, 23% a D, and 15% an F; 2% refused to answer the question. 6% gave him an A, 22% a B.)

To see all eight poll results that the FOP released to the media, click this link (354 KB PDF file).

Steve Lackmeyer of The Oklahoman reports that an Oklahoma City citizens' committee (featuring heavy hitters like Larry Nichols of Devon Energy and immediate past Mayor Kirk Humphreys) has recommended a site other than Mayor Mick Cornett's preferred site for the new convention center, funded by the MAPS 3 sales tax. It appears that the original cost analysis, favoring Cornett's preferred site just south of the Arena Formerly Known as Ford, was badly skewed by using "cost premium" factors and by ignoring the $30 million cost of relocating an electric substation.

- The MAPS 3 Program Manager was caught out on several claims that the City Council had instructed him to reallocate money from the $280 million convention center budget to pay for substation relocation and to prioritize completion of the core-to-shore park; no such votes were ever taken.

- I wonder whether there is any connection between the Momentum attempt to stack the council and this dispute over the convention center and core-to-shore development. (Core-to-shore involves redevelopment of the area between the current I-40 alignment on the southern edge of downtown and the North Canadian River.)

- When Tulsans suggested alternatives to the BOK Center location after the Vision 2025 vote, Mayor Bill LaFortune said it was set in stone. In Oklahoma City, not only has there been a public debate about the best location for the new convention center, the big shots are not afraid to disagree publicly with one another.

- Not only are locations not set in stone, but Kirk Humphreys is urging that the need for the proposed regional park for the Core-to-Shore area be revisited, in light of changing conditions downtown since the plan was drawn up five years ago.

MORE: Nick Roberts doesn't like the decision:

Too weary to go into all of the reasons why this is a horrible site, for OKC that is, I mean it's great for the conventions... well actually, first we're going to have a big vacant lot between the two parks for ten years until we break ground on the CC. Unless they get to move the site up, in which case, we won't get as much mileage of streetcar track because of this decision. Or something else would be impacted.There might be some interesting solutions that can alleviate the negative convention center impact we're about to add downtown. I'm more interested in pursuing that public debate than attempting to oppose yet another high-profile decision that was already made mostly behind closed doors.

The new issue of the Oklahoma Gazette covers the recently concluded Oklahoma City city council elections, in which candidates backed by a shadowy special interest group won all but one contested race.

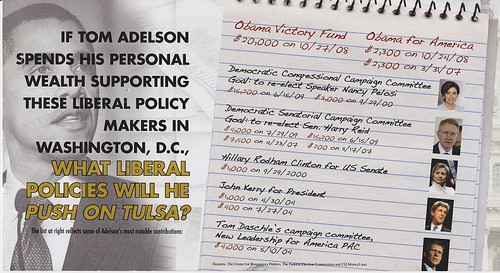

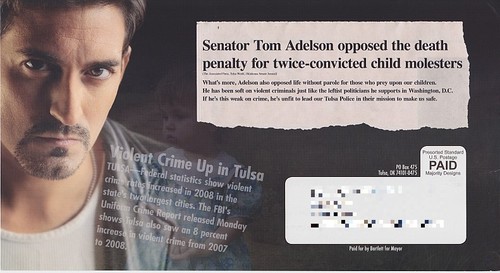

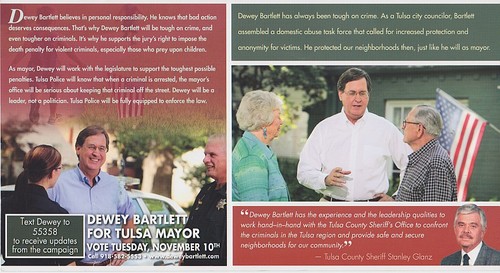

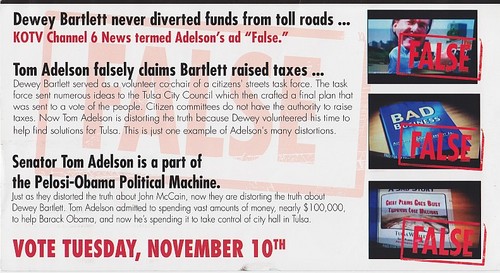

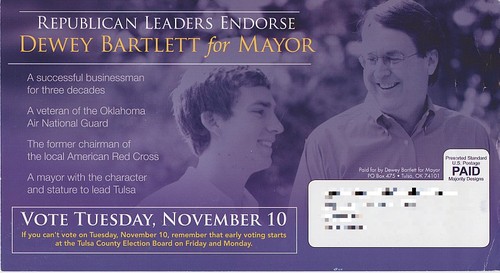

The story notes (as was speculated on BatesLine last month) that Majority Designs, the same campaign team that produced the mailers for Dewey Bartlett Jr's campaign for Mayor of Tulsa in 2009, produced the campaign materials for the Committee for OKC Momentum. Majority Designs is an affiliate of AH Strategies, Karl Ahlgren and Fount Holland. Here are four of the Bartlett Jr mailers I received during the general election campaign, connecting Democrat nominee Tom Adelson to national liberals, tagging Adelson as soft on child molesters, making questionable use of a couple of Disney characters to call Adelson a liar, and a piece listing endorsements from Tom Coburn, Jim Inhofe, and John Sullivan.

Oklahoma towns and cities with a statutory charter (which is to say, no charter at all; they are governed by the default provisions of Oklahoma Statutes Title 11) and some charter cities have elections today, Tuesday, April 5, 2011. Some school board seats will have a runoff, if none of the candidates received 50% of the vote back on February 8.

Here in Tulsa County, Broken Arrow, Glenpool, Jenks, Sand Springs, and Skiatook each have city council or town trustee races on the ballot. It's encouraging to see that nearly every seat up for re-election has been contested.

Broken Arrow and Bixby electorates will each decide four municipal bond issues. Broken Arrow's bond issues cover streets, public safety, parks, and stormwater. Bixby votes on streets, public safety, and parks, and an amendment to a street project approved in a 2006 tax vote.

Tulsa Technology District (vo-tech) Zone 2 has a runoff between former Tulsa Police Chief Drew Diamond and Catoosa school superintended Rick Kibbe (both registered Democrats). The two candidates each received less than 100 votes in the snowbound February primary. Skiatook has a runoff between Linda Loftis (registered as a Republican) and Mike Mullins (registered as a Democrat) to fill an unexpired term for seat 3.

Oklahoma City has a high-profile council runoff, too, between a candidate backed by the shadowy Momentum committee and physician Ed Shadid. Shadid seems to be drawing support from a wide range of Oklahoma City bloggers; the list of endorsers includes Charles G. Hill of Dustbury, Oklahoma City historian Doug Loudenback, young urbanist Nick Roberts, and slightly older urbanist Blair Humphreys.