MIT Category

Paul Gray, president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology from 1980 to 1990 and the man who handed me my college diploma, died today at the age of 85. Gray was the last true MIT nerd to hold the post, possibly the last who ever will. In his years in the MIT administration, Gray managed to improve the undergraduate experience and broaden the base of potential MIT students while preserving the school's distinctive ethos that he had known since his undergraduate days.

Paul Gray, president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology from 1980 to 1990 and the man who handed me my college diploma, died today at the age of 85. Gray was the last true MIT nerd to hold the post, possibly the last who ever will. In his years in the MIT administration, Gray managed to improve the undergraduate experience and broaden the base of potential MIT students while preserving the school's distinctive ethos that he had known since his undergraduate days.

In the 2008 Infinite History interview with Paul Gray tells his life story in his own words (the link leads to a transcript), and what follows is a summary and excerpts that I found interesting.

Gray, the son of an electrical utility technician, started experimenting with electricity and magnetism as a first grader, began building and repairing radios with vacuum tubes at the age of 10, and became an amateur radio operator in high school, building his own equipment. Accepted to RPI, Yale, and MIT, Gray signed up for MIT at the urging of his high school English teacher:

GRAY: ... I was admitted to all three. But MIT was the only one that didn't offer me any money. The other two made it quite easy to go. And I was about to go to Yale, which it offered the most, when I had a conversation with really my first mentor besides my family. And that was my English teacher in high school: had her for four years. Emily Morford. M-O-R-F-O-R-D. And I told her-- she knew where I'd applied, she wrote a reference-- and I told her what my tentative decision was and she took me to the woodshed. And she said, "You can't do that. If you have a chance to go to MIT that's where you should go. It's the best place to study engineering."INTERVIEWER: Now wait a minute, this is the English teacher telling you?

GRAY: The English teacher, English teacher. Who lived long enough to see me elected president here. What, 1950 to 1980, 30 years later. She couldn't come to the inauguration. She was in her 90s and lived in Florida, but she knew about it. She had been an important-- she was perhaps the teacher in high school that I remember the most. And that includes chemistry and physics and biology and mathematics. And it was her influence that pushed me the other way. I went back and the family said, "Well we can manage that. Do it." So that's how it happened.

I can't resist quoting what Gray said about how he learned to write and the disconnect between SAT scores and actual verbal skills:

GRAY: ... I've always enjoyed writing and do a lot of it. And maybe that's part of it because she taught writing, she taught the English language, the way it should have been taught. You know we diagrammed sentences, we worked on paragraph structure, the whole nine yards. And I came out of high school I think being a pretty good writer. And it paid off in later years here, still pays off.INTERVIEWER: Do you think many MIT students can diagram a sentence today?

GRAY: No, too many of them can't really create a sensible sentence, let alone a paragraph. It's astonishing to me. I mean MIT students come here with an average verbal school of something like 750. But still most of them are abominable writers. Not all-- I mean, some are very skillful. Some have learned the craft. But a great many of them come here needing a boost in their writing, which they get.

Gray was the last of a series of five presidents with connections to the Institute prior to taking office, and one of three who had attended the university as undergraduates. Gray's two immediate successors had no prior connection to the Institute; the current president, L. Rafael Reif, joined the MIT electrical engineering faculty in 1980 and has been at MIT ever since.

As an undergraduate, Gray found a home away from home and lifelong friends in an MIT fraternity, Phi Sigma Kappa:

During the summer, in those days, freshmen got visited by fraternity students because when you arrived here, you had to make a choice between whether you were going to live in a dormitory or live in a fraternity, pledge a fraternity. And I had a visit that summer from two students, both of them living in New Jersey, and I said, "No, I'm not going to rush week. I'm going to live in the dormitory." I already had an assignment in East campus which was then all single rooms. And I lived there through, about through Thanksgiving, but found it was intensely lonely, partly because all the folks around me in that dormitory were GIs who had come back from World War II. You know, the largest class ever to graduate from MIT was the class of 1950, because it swept up all the guys who had had their education interrupted in the early '40s. And the GIs who returned were very single-minded about their studies. They were not involved in any social life or other activities that eighteen-year-olds would be involved in. And I just felt isolated.So as it happened, the two students who had visited me in the summer showed up again one evening and visited me at the dormitory and said, "Why don't you come over and have dinner?" Well I did. And that opened my eyes to a very different style of living at MIT. To live with 28 other people in a four-story house on Commonwealth Avenue. And so I moved into the house in December and lived there for the next three-plus years. Three-and-a-half-plus years. And that was also an important learning and living experience for me because I was an only child. I had only two cousins, one on each side of the family, saw them seldom and really had grown up without-- had neighborhood friends, to be sure, but their interests were different from mine-- had never had an association with other people my age whose interests overlapped with mine. And I had a role there eventually in governance of the place, as well as most people did, and it was a great experience....

The living members of my pledge class, of which there are about five or six, we get together every September for a clam bake at one or another's house. This year it's at our place.

Gray received his S. B. in Electrical Engineering in 1954, his S. M. the following year, and then decided he'd "had it" and was leaving MIT, never to return.

After two years in military service, which involved teaching GIs in the use and maintenance of listening devices, Gray came back to MIT in 1957 and received his Sc. D. in 1960. Gray's doctoral research involved developing compound semiconductor materials for new applications, in which he had to develop the techniques to make the materials himself in an induction furnace: "Nobody to teach me the techniques, to how to do this in a way that would produce crystalline materials. It was a real challenge."

During his military service and doctoral studies, Gray discovered that he loved teaching. As a new faculty member, Gray became a leader in redirecting the electrical engineering curriculum from vacuum tubes to semiconductors. In the late 1960s, Gray was asked to move into higher positions of administrative leadership, serving as an associate dean of student affairs, associate provost, and dean of engineering. When Jerry Wiesner became MIT president, he asked Gray to become his deputy as chancellor of the Institute.

I'll let you read for yourselves Gray's role in the creation of the Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program and his description of the pragmatic and peaceful process that led MIT to reach out deliberately to encourage members of minority groups and women to apply. (Prior to 1968, MIT did no recruiting at all and accepted about 25% of applicants.) I'll close by focusing on a couple of anecdotes that epitomize Gray's leadership as president.

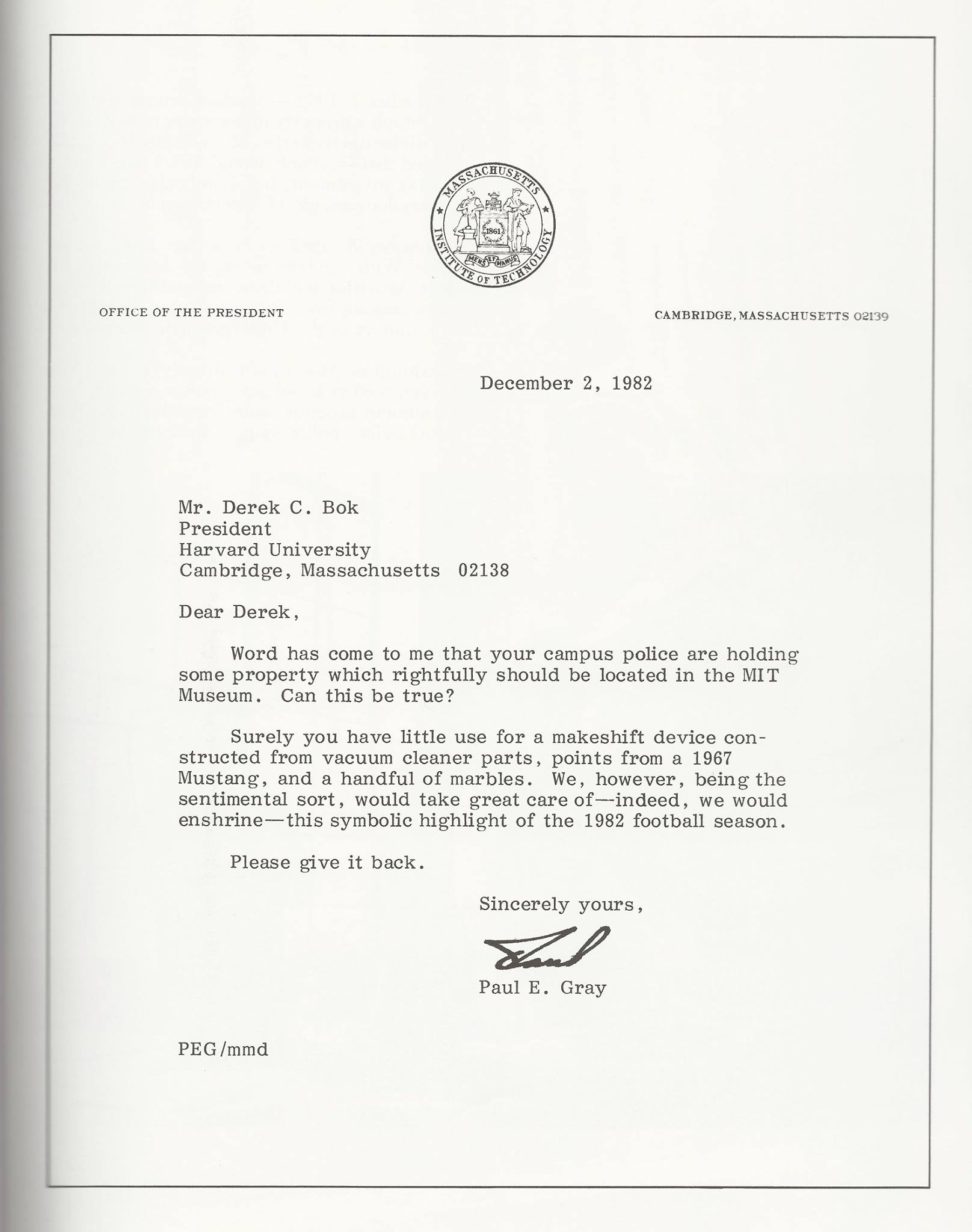

In the fall of 1982, MIT's chapter of Delta Kappa Epsilon (DKE) planted and inflated a weather balloon marked MIT in the middle of Harvard Stadium during the Harvard-Yale game, a stunt regarded as the greatest hack in MIT's history:

Dear Derek,Word has come to me that your campus police are holding some property which rightfully should be located in the MIT Museum. Can this be true?

Surely you have little use for a makeshift device constructed from vacuum cleaner parts, points from a 1967 Mustang, and a handful of marbles. We, however, being the sentimental sort, would take great care of -- indeed, we would enshrine -- this symbolic highlight of the 1982 football season.

Please give it back.

Sincerely yours,

Paul E. Gray

A few years later, enrollment in Course VI, the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, as the first generation of students who had begun working with computers in high school arrived on campus. MIT had always allowed students to choose a major without jumping through any additional hoops, but the crowding in Course VI led to talk of entrance restrictions. The crunch led Gray back to the classroom to "shame [his] colleagues":

In the middle 80s, the enrollment in electrical engineering and computer science was exploding. And it started out the decade at about 200 per class, 200, 250 per class. And by 1985 it was up to 350. And there was concern that if the trend line continued, it was going to go past 400. It was more than the department could staff and manage. And what's more it beggared all the other departments, who said, "Where are my students? They're all in EE!"And the department at that point was desperate to get more people to teach sections. And a number of folks who were faculty members of EECS, but were also laboratory heads, were saying, "Gee, I just don't have time for that." So, I figured if I showed up and taught two sections for a couple of semesters, some other people might catch on. And they did. It made some difference.

The trend line began to turn as other departments began to offer classes in computer programming, as applied to each discipline. "That drained off some of the students that otherwise would have thought they had to be in Course VI in order to learn to be computer scientists."

Those of us who were at MIT in the 1980s were blessed to be there under a leader who remembered what it was like to be in our shoes, who understood the value of the residential community (be it fraternity, independent living group, or dorm entry) as home-away-from-home, and who, without embracing political correctness or institutional fascism, navigated societal change with MIT engineering pragmatism. May his memory be a blessing.

Noteworthy news, comment, and reflection:

MIT's student newspaper The Tech reports on the memorial service for campus police officer Sean Collier.

MIT Police Chief John Difava recounted the events of last Thursday night. He was pulling out of Stata around 9:30 p.m. and saw a cruiser idling, which turned out to be Collier. "I asked him what was going on, and he gave me that famous grin," said DiFava, "and said 'just making sure everybody's behaving, sir.'" An hour later, Collier would be shot.DiFava also spoke about all of Collier's qualities, stories of which have been pouring from the community this week: He was a gentle and caring man, and police work was his calling. Sean wanted to be a police officer from the age of 7, said DiFava, and paid his way through the police academy with no promise of employment, waiting for a department with an opening. "That lucky department would be us."

The LA Times spoke to neighbors and acquaintances of the (alleged) bombers, including members of a mosque where they worshipped, the Islamic Center of Boston mosque in Cambridge. Some told of a recent, angry outburst by the older brother.

Tamerlan Tsarnaev was thrown out of the mosque -- the Islamic Society of Boston, in Cambridge -- about three months ago, after he stood up and shouted at the imam during a Friday prayer service, they said. The imam had held up slain civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. as an example of a man to emulate, recalled one worshiper who would give his name only as Muhammad.Enraged, Tamerlan stood up and began shouting, Muhammad said.

"You cannot mention this guy because he's not a Muslim!" Muhammad recalled Tamerlan shouting, shocking others in attendance.

He returned to the service later without further incident, and other mosque members say he wasn't thrown out so much as taken aside and calmed down.

(Interesting contrast between this situation and a Tulsa man who said he was intimidated by leaders at his mosque and effectively kicked out because of an op-ed he wrote condemning violence in the name of Islam.)

A week ago, Judicial Watch found that bomber Tamerlan Tsarnaev's 2009 arrest (not conviction, but the arrest by itself) for domestic violence was sufficient justification to have had him deported. That article also links to other documents about al-Qaeda's involvement in Chechnya.

Ace of Spades HQ has a lengthy analysis of the decision to read a Miranda warning to Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, who immediately stopped talking. Ace notes that if may be worth sacrificing the ability to use the suspect's statements against him in a court of law in order for a greater purpose -- finding out who else still out there may have been involved.

Ace also links to this: In Paris this week, a rabbi and his son were slashed and wounded by a man wielding a box cutter and shouting "Allah-u-akbar!"

In the Telegraph, columnist Brendan O'Neill wonders why American liberals seem to be more worried about the reaction of some Americans to a radical Muslim motivation behind the bombing than about the bombing itself.

Todd Stewman, a church planting pastor in Austin, Texas, was at the finish line just minutes before the attack and not long after his wife had finished running the marathon. He reflects on the providence that had him away from the finish line and around the block when the bombs went off, while others were killed and maimed. He asks, "Where was God on Boylston Street?" Where is God in suffering?

Jesus, more than anyone in human history, suffered as an innocent.... God's hand was on him through it all. Jesus was perfectly at the center of the Father's will, even when he was suffering. What does this mean for us? It means that suffering does not indicate the absence of God. It means that God is with us in the midst of suffering. Jesus is the fulfillment of Psalm 23:4, "Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil, for you are with me." The only reason we can know for sure that God is with us through evil and suffering is that the Son of God waded into a broken world, experienced suffering himself, and overcame it. The death and resurrection of Jesus Christ does not eliminate all suffering now, but it does guarantee that suffering will one day be eliminated ultimately when he comes again. The death and resurrection of Jesus tells us that God has not ignored evil and suffering, but that he has done something decisively about it. God has dealt a final blow to death by raising Jesus from the dead, and one day there will be no more death and suffering.So, if I had died or been badly injured on Monday, God would no less have been with me. My safety and security are gifts from God, for which I am most certainly thankful. But my safety and security are not the litmus test of his presence and goodness. His presence and goodness are evidenced by the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus, who "took up our pain and bore our suffering (Isaiah 53:4)."

Julie R. Neidlinger ponders how we respond emotionally to a far-away tragedy -- our rebellion against the thought that we aren't really in control, our desire to express care and concern to the victims without the means to do so in substantial ways, and how blind we can be to those who are within the reach of our help. There's so much insight here, it's tempting to quote the whole thing:

We post sad sentiments and outrage and images on social media. We like and share them and hope it changes the future so that it will never happen again. What else can we do to banish this bad thing? And then politicians mistakenly think their reason for existence is to legislate something so the human condition of pain and suffering doesn't rear its ugly head again."If something terrible ever happens to me, " I told my friend, "I don't want to be the excuse for bad legislation. I don't want to be memorialized as a victim. I didn't live 40 years on this planet to be remembered for a few final ugly moments and a fight in some elected political body in an attempt to make human nature illegal."

Tragedy and evil are not completely within our control. We make lots of noise and pretend it isn't so....

We're an ephemerally-connected world. We have a strange problem of being instantly connected to the news of what's happening but unable to do anything substantially. We can give money. Post to Facebook. Tweet. Use emoticons. Click "like".

But grief is best handled in person by people close to those affected, in actual physical proximity, and I can't do that on Facebook....

When something bad happens in the world, I realize I don't want to be able to weep huge tears for hurting people across the country and not feel anything for the actual people God put in my life.

The best thing I can do now is show my family and friends love.

I can let the people in my life know my thoughts are with them by sending a card or a bouquet of surprise flowers or talking on the phone even when I have work that I need to do. Little things are big things; they accumulate. Thinking kind thoughts are of little use if the person doesn't know you, and doesn't know you're thinking about them.

The best thing we can do when tragedy strikes elsewhere is make sure love happens here. Make the small world you're a part of better as a fight against the spreading darkness.

Back on Monday, April 22, 2013, Rob Port reported that U. S. Senator Frank Lautenberg is proposing black powder control in response to the Boston Marathon bombing. Port notes two possibly unintended consequences: (1) Restrictions on gunpowder hinder reloading of spent ammunition, which was one way around ammunition shortages. (2) Unable to get professionally-made black powder, some may resort to manufacturing their own, which will be lower quality and potentially more dangerous:

Here's the thing: Building explosives isn't hard. You can find recipes for making black powder and other explosives/incendiaries in library books. Of course, the problem with home-made black powder is that it's not very good. It'll go boom, just not as reliably.By restricting access to professionally-made black powder, we're probably doing more to ensure more accidents with people trying to make powder at home than preventing the sort of terrible but, thankfully, rare attacks such as the one in Boston.

(UPDATE: See-Dubya calls my attention to this: One of the bombers bought a couple of large reloadable mortars with 24 shells at a fireworks store across the border in New Hampshire. The store's owner estimates he might have been able to harvest 1.5 pounds of black powder by dismantling the shells. Lautenberg's proposal wouldn't have caught a purchase like this.)

Writing at Next City, MIT urban planning student Andy Cook writes about the eerie quiet on the streets of Boston during the "shelter-in-place":

It was a strange walk studded with realizations of what my neighborhood looks like without the faces that usually draw my attention. There were things I pass everyday that I had never seen before. A cluster of low-slung row houses that had been standing for the last 100 years. Another home being built across the street -- how had I missed the gap that must have been there before? There were flowers, of course, everywhere, and the cashier that sold me a jar of ground coffee gave me the sweetest, saddest smile I've seen in a long time. The only sound I heard as I walked home was wind in the trees, and my own footsteps. My neighborhood was peaceful.

Further on in Cook's article, though, I get the distinct impression of "mission creep" in the realm of urban planning (see Neidlinger above about legislating to abolish human nature):

Many of us came to the department with a do-gooder mentality. We were motivated to pursue planning because we thought it could address the inequity we saw in the world. We felt (and feel) that structural inequality is at the root of societal problems we face on a daily basis, violence and despair among them. Planners are uniquely poised to bring a holistic approach to cumbersome and intractable issue....More likely, [as professional planners] we'll have to make decisions about policies and resource allocations that help some and hurt others. The challenge of this is two-fold: To understand the complex systems well enough to plan for unintended consequences, and to make sure the consequences won't cause disruption or disenfranchisement that might lead a population to turn to violence as a means of protest, retribution or survival...

Deciphering the "why" behind the Boston Marathon bombing and subsequent manhunt will be a long and contentious task. For some, it will begin and end with the biography of the bombers themselves. But we should press further, and follow with a close examination of the global systems that foster inequality, breeding hatred and violence internationally. We as Americans and as planners especially must never stop considering the unintended consequences of the systems we live by. We must measure impacts and decide when and how to retool those systems that are broken, that allow for days like Monday to occur.

Those of us who are Christians know that the ultimate brokenness is in the human heart. We can and should work to mitigate the effects of evil, and city planning can be a means to do so, but we will not be able to eradicate evil in this world.

I was up late last night anyway, but when my wife told about reports of a shooting at MIT, I tuned in to Twitter and the live streaming coverage of WCVB in Boston as they took phone calls from frightened residents of a neighborhood in Watertown where shots were being fired and explosions were being heard.

MIT campus police Officer Sean Collier, 26, was fatally shot at around 10:48 PM EDT. The shooting occurred near Building 32, the Stata Center, the relatively new electrical engineering and computer science building designed by Frank Gehry. It's in the more industrial backside of campus, along Vassar Street, and not near any dorms, but MIT being what it is, there were undoubtedly some students working in the labs.

After the shooting there was a carjacking a short distance away, the carjack victim was released about a mile or so west of MIT on Memorial Drive (a boulevard that follows the north bank of the Charles River), and then shots fired and explosions in a neighborhood in the eastern part of Watertown, near its border with Cambridge. In the end, they found the second perp in a boat, under the boat cover, in someone's backyard in that same neighborhood.

A geographical note: Massachusetts is divided into 351 municipalities, with no unincorporated area, and in the Boston area you can go from one city or town to another every few miles without noticing. The Watertown neighborhood where the shootout with police occurred and where the second suspect was apprehended is about 3.5 miles by car from MIT's Building 32. Each town and city has its own police department, and there's also the state police and the MBTA transit police -- several different law enforcement agencies were involved in the pursuit.

It's now believed that the two involved in the shooting of Officer Collier were also the perpetrators of Monday's Boston Marathon bombing. One wonders why they were at the MIT campus. Were they there to plant more bombs? Was the shooting of an officer itself the intended act of terror? Or was Officer Collier shot because he was in the way of a more deadly plot? Or was it because he recognized them as persons of interest in the Marathon bombing?

The suspected perps are Tamerlan Tsarnaev and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, two brothers, originally from the region of Chechnya in the Russian Federation. Tamerlan could have been deported four years ago because of a criminal domestic violence arrest, but the Federal government allowed him to stay.

When the Soviet Union broke apart, the Chechens sought their own independence from Russia. In 2004, Chechen terrorists captured a school at Beslan and 334 hostages were killed. The Chechen insurgency was ultimately crushed by Russia. Were the Tsarnaevs motivated by Chechen nationalist resentment -- and if so, why take it out on America, which wasn't involved in that dispute? -- or by Islamic radicalism more generally?

Thinking back to my own time at MIT, I can't recall ever feeling afraid on campus (or in most parts of Boston, for that matter). It was a safe place, even late at night, despite some less than salubrious housing projects nearby. Campus Police played an important role in maintaining that sense of security, and security measures have only increased in the quarter-century since my graduation.

Our thoughts and prayers go with Officer Collier's family and friends, and I hope that the campus soon returns to its usual sense of security.

MORE: The Boston Herald has a timeline and map of the MIT shooting and the subsequent manhunt.

January at MIT is neither fall semester nor spring semester. It's the Independent Activities Period (IAP). Students can choose to stay back in their hometown, travel, or come back to campus, and once on campus there are hundreds of activities to choose from. Nearly every department offers for-credit courses in special topics or accelerated versions of core courses. Then there are the unofficial activities: You can change-ring the bells in the tower of the Old North Church in Boston. You can learn Israeli folk dancing and the Argentine tango. You can learn table manners, knitting, trash can drumming, and how to build your own guitar delay pedal. You can play quidditch in the snow. Bell Helicopter is giving a half-day Introduction to Rotorcraft. A couple of Ph.D. candidates are offering a week-long Introduction to Modeling and Simulation.

One of the evergreen MIT IAP activities is a lecture by Computer Science professor Patrick Henry Winston on the heuristics of giving a lecture so that you succeed in communicating your ideas to your audience. I heard the hour-long talk when back when I was an undergraduate, 29 or 30 years ago. It's being offered once again this year, and a few years ago, the talk was captured on video:

MORE: The edX consortium -- MIT, Harvard, and University of California at Berkeley -- offers free online courses in which you can earn a certificate of completion. MIT's offerings include Introduction to Solid State Chemistry (the chemistry course typically taken by majors in electrical engineering and computer science), Introduction to Computer Science and Programming, and Circuits and Electronics. The work load is real -- they estimate, for example, 12 hours per week time commitment for Circuits and Electronics -- and you progress through the material at a set pace.

STILL MORE: One IAP class is called "Designing Your Life." You can take the Designing Your Life course as self-paced study through MIT Open Courseware. Here's the synopsis and a "trailer" for the course:

- Promises and consequences, areas of life: We learn how to develop your personal integrity by making and keeping weekly promises to yourself.

- Theories: We identify theories you have about the way the world works, and discuss how they impact what you see as possible and impossible. We learn how to author new theories that better align with our dreams.

- Theories, purges, and thought logs: We hunt for theories by recording our thoughts throughout the day. We also learn how to rid, or purge, the mind of destructive thoughts that keep us from honoring our promises to ourselves.

- Excuses: Every time your life does not resemble your dream life, there is likely an excuse that takes the responsibility for being great off your shoulders. We learn how to identify and debunk the excuses that are holding us back.

- Parent traits: Many of our personal traits are formed in reaction to our parents. In this lecture we study this concept more deeply, and identify how our parents' traits live within us.

- Haunting incidents: Incidents from our past that haunt us contain valuable clues to lessons we need to learn. In this lecture we learn how to find haunting incidents in our lives.

- Cleaning up haunting incidents: We learn how to clean up and resolve hauntings so they do not haunt us anymore, and so we can feel proud and confident in our skin.

- Connecting haunting incidents, traits, and theories: We explain how hauntings arise from our traits and theories, and as such can provide valuable insights on what we need to evolve to reach our goals.

Trinity Episcopal Church, 5th and Cincinnati in downtown Tulsa, will host two concerts this weekend featuring beautiful Christmas music in its Gothic Revival sanctuary.

On Friday night, December 21, 2012, at 7:30 pm, the Tulsa Boy Singers will perform a concert of Christmas and winter music Tickets are $10, and available at the door. Student admission is free. TBS's junior choristers as young as six will be joining the singers on a couple of songs. A reception will follow.

The TBS program includes familiar carols like Good King Wenceslas and In the Bleak Midwinter, ancient carols like Coventry Carol and Personent Hodie, and more modern seasonal songs like White Christmas, Jingle Bells, and It's the Most Wonderful Time of the Year.

The Tulsa Boy Singers, now in their 65th year of existence, is made up of boys from 8 to 18 who rehearse twice weekly and are trained in vocal performance and music theory. If you know a boy age 6 or older with an interest in singing, there will be an opportunity for a brief audition after the concert. TBS was my oldest son's first musical activity, and what he's learned from director Casey Cantwell and assistant director Jackie Boyd has laid a strong foundation for everything he has done with music since, teaching him to read music, to follow direction, to blend with others, to feel confident performing in public, and to appreciate great music. I'm thrilled that my youngest son has the same opportunity and only wish as strong a program existed for Tulsa's girls.

On Sunday night, December 23, 2012, at 7:30, the Tulsa Symphony Brass and organist Casey Cantwell will present a concert of Christmas music, part of the Saint Cecilia Concert Series. Tickets are $20 ($10 for students and seniors), may be purchased in advance online, and will be available at the door.

One of my favorite memories of this time of year at MIT was walking out of the December chill and into Lobby 7 on my way to class in the morning and being greeted with a brass quintet playing Christmas carols, which filled that vast space. I imagine Sunday's concert will bring those memories back to life.

25 years ago today, I sat in MIT's Killian Court along with a thousand other students in a heavy academic gown made heavier by a steady rain. Officials thought the rain would hold off, but by the time it became apparent that it would not, it was too late to redirect graduates, diplomas, and well-wishers to the alternative indoor sites.

It was a fitting conclusion to the odd final act of my time at MIT. A couple of weeks into the spring semester of my junior year, chest aches and fever were diagnosed as acute pericarditis. The doctor sent me straight to the infirmary, and within a week I was watching as a surgeon stuck a needle into my chest to drain a half-liter of fluid as a crowd of residents looked on. (Mt. Auburn Hospital was a teaching hospital.)

After a week of recovery time, I tried to jump back into academic life, but the pericarditis came back, along with high fever and heart rate. A few more weeks later, I had been ordered to go home and recuperate. There were further recurrences, much less severe, a couple of times a year over the next nine years, treated with rest and indomethacin, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory. (I'm pretty sure a couple of chest colds from years earlier were symptoms of the same problem.)

The missed semester threw the whole graduation plan off, thanks to courses offered only in the fall or spring. I came back full-time for the '84-'85 year, spent fall '85 working and taking one class, and then finished up in the spring of '86. The disruption to my plans inspired the essay I wrote for the yearbook -- I'll post that separately, later.

A significant recurrence struck at the beginning of my final month of school, and I had to give myself space to recover. With the department office, I determined I didn't need the Aeneid course at Harvard for graduation, so I punted it. I had an A in 6.045 (Computability, Complexity, and Automata); the professor said I could punt the final entirely and still get a C -- not pretty, one of a handful of non-As, and the only one in a class in my major, but I needed to cut way back on the pressure so I could rest and get healthy. I still had a final in Medieval and Church Latin at Harvard that the prof let me take at a later time. (Can't think of the other class I had that semester.)

Oh, about my major: I had planned to pursue computer science, although I was open to urban studies or political science. The first lecture of the initial urban studies class was so blatantly left-wing on matters incidental to urban policy that I dropped the class and the idea of majoring in Course XI. During the first semester of my sophomore year, I worked out a plan that would give me an education in computer science but would include a humanities component that was stronger than usual for MIT -- specifically, classics, which was not a major MIT has ever offered. I put together a classics component from Latin classes taken by cross-registration at Harvard and a couple of ancient Greek and Roman history classes offered at MIT. The dual major in humanities and engineering got me two-thirds of the standard program in each of computer science and classics but would still let me finish in four years. I wrote up a proposal and got the necessary approvals. (The rules were changed after the fact to require a majority of classes in each component of the dual major to be taken at MIT.)

My parents and sister were coming for commencement, and the night before we were going to have dinner at Uno's at Harvard and Comm Ave in Allston with a high school classmate who worked in Boston. Their arrival from my uncle's house in New Jersey kept getting pushed back. (The delay was because my little sister realized she left her boyfriend's photo at our uncle's house, so they had to retrace winding roads to fetch it. Thankfully, this was not the boyfriend she eventually married.) (Thinking back on this, it's hard to remember how we managed back then without cell phones.)

Back to graduation day, and it's raining steadily. One parent was heard to say, "After the soaking I've taken from this place for the past four years, what's a little rain?"

We sat through what may have been the dullest commencement speech ever. The speaker, one of the founders of Hewlett-Packard, had apparently never read the speech before stepping up to the podium to read it, ploddingly, to us. (I had to look it up, but the speaker was William Hewlett, who received a Master's from MIT in 1936.) You can read Hewlett's speech on page 5 of the June 24, 1986, issue of The Tech (PDF), but you'd be better off reading columnist Andrew Fish's summary on page 4:

Inside or out, the audience still had to be content with the address of William R. Hewlett SM '36. This was unfortunate. Hewlett's own title, "Random Thoughts on Creativity," was certainly appropiate. I had trouble following the speech, as it wandered aimlessly around, never reaching a firm conclusion....The biggest complaint I have against the speech, though, was its stereotyping of the MIT community. Hewlett treated the entire class as if they were engineers going into industry. The speech was not a broad message to the entire graduating class, rather a lesson on how to be a better engineer....

I also urge the commencement committee to be more creative in their speaker selection. Graduates should be able to hear a speech with vision, and not another lecture, at the end of their long career.

'85 got Lee Iacocca and sunshine, for heaven's sake.

We then had to endure the lengthy remarks of our class president, who had a seat under the canopy and was evidently indifferent to her soggy classmates' plight. (I seem to recall many of us shouting "Finally!" until she skipped ahead to her conclusion.)

Finally, we lined up to march across the stage and receive our diplomas from President Paul Gray. (There was a joke: MIT's skies are gray, the walls are gray, the buildings are gray -- even the president is Gray!)

That's President Gray in the gray and cardinal robes shaking my hand and about to hand me my diploma. The rain doesn't show up on my black robe (although the robe's cheap dye showed up all over the dress shirt I was wearing), but you'll notice the mud and moisture on the cuffs of Gray's gray trousers. Behind his back, Dean of Undergraduate Education Margaret MacVicar is reading the names, and in the background next to my left shoulder is former President Julius Stratton.

After the ceremony I met up with my parents and sister, went to a reception for my department, then connected with some of my Campus Crusade friends. After that, we dropped by the fraternity house so I could show my folks around. A brother gave me a copy of the Wheel of Fortune home game as a gift -- watching Wheel was a nightly ritual in our apartment, a four-bedroom flat in a brownstone at 128 Fuller St. that the fraternity leased for overflow housing. (We even named our victorious "treasure hunt" (road rally) team the Wheels of Fortune.)

Beyond that the memories grow dim. Seems like I ought to be able to remember where my sister and parents stayed that night, where we ate dinner. I remember that they couldn't spend as much time in Boston as I had hoped; Dad, who had been laid off by Oxy (Cities Service) the previous September, had a new job in another city. It was just one more way that graduation fell short of my hopes.

I remember seeing them off at Logan with several boxes of my stuff to take along as checked luggage. A few days later, I packed my grandfather's old Sedan De Ville with all my belongings and headed back to Oklahoma, where I had a girlfriend (almost in Oklahoma -- in Fayetteville) but no job yet. I took my time going home the southern route, enjoying gas at less than 60 cents a gallon, seeing my uncle in northern New Jersey, friends in Charlottesville and Birmingham, and my girlfriend in Fayetteville before pulling into the driveway in Tulsa.

I bought a little portable stereo at Radio Shack so I could listen to cassettes and record my thoughts as I drove. I still have the stereo, and I'm sure the cassette is around here somewhere. It would be interesting to hear what was on my mind.

This is my first trip back to Boston in about 15 years. I'll be attending some of the reunion activities and going to a reception and dinner in honor of my fraternity chapter's centennial. It's an opportunity to remember where I've come from and think about where I'm headed for the next 25 years. A prayer for clarity and inspiration would not go amiss.

UPDATE 2013/05/30: Revisited this entry after responding to a Colin Quinn tweet imagining himself as MIT's commencement speaker, and I think I remember a couple of details that I had forgotten when I wrote this. My parents and sister stayed at the Travelodge at Beacon and St. Paul in Brookline which was under renovation. It's now a Holiday Inn. If I recall correctly, I brought them bagels from Kupel's the morning after commencement. (Kupel's bagels were a Sunday morning tradition at ZBT. We even had an officer -- bagel chairman -- in charge of acquiring them.)

As for dinner the night of commencement, for some reason I remember a disappointing meal at 33 Dunster Street. Perhaps it was the next night that we had dinner at Chef Chow's in Coolidge Corner.

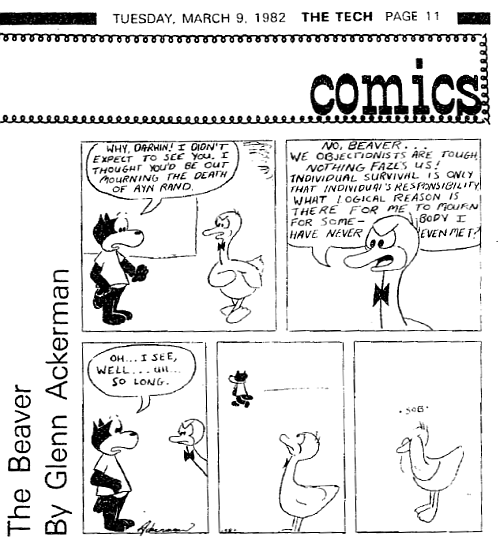

It's odd what sticks with you over the years. A blogpal's Facebook quotation of a surprisingly emotional and romantic passage from Ayn Rand's novel Atlas Shrugged (the film version debuts this weekend) was a reminder that Rand and her admirers were not exactly Vulcans, and it brought to mind a cartoon that was published in The Tech, MIT's student newspaper, in the issue following Rand's death in 1982 (PDF). Thanks to the miracle of the Internet, I could find the comic strip, which features two anthropomorphic animals as MIT students, Beaver, the protagonist, and Darwin the Duck, who belongs to MIT's "Objectionist" Society and works on the Ego. (There was a weekly newspaper called Ergo, published by objectivists from MIT and other area colleges.)

I could easily get lost browsing through issues of The Tech from college days. All 131 years of The Tech are online. In 1982, there was a well-drawn, consistently funny strip called Space Epic by Bill Spitzak -- still funny after all these years. Spitzak was a computer science major and went on to develop the Nuke compositor for use with computer-generated special effects, first used in the movie True Lies.

In that same issue, the Tech Coop advertised a special deal on cases of Coke and Tab -- 24 cans for $5.99 (regular price $8.75). It's amazing to think you can still get a case of soda for the same price, when it's on sale.

A few issues later, there was this front page chart with MIT admission stats for application years 1980, 1981, and 1982. I've added the stats for the most recent two years from reports in The Tech (for 2010; 2011):

| 1980 | 1981 | 1982 | 2010 | 2011 | |

| Applicants | 5643 | 5893 | 5790 | 16,632 | 17,909 |

| Acceptances | 1773 | 1694 | 1884 | 1,676 | 1,715 |

| Waitlisted | 335 | 429 | 300 | 722 | |

| Men | 1349 | 1249 | 1414 | 53% | 51% |

| Women | 429 | 445 | 470 | 47% | 49% |

| Minority | 147 | 170 | 182 | 23% | 26% |

| Foreign | 55 | 52 | 68 | 7% | 8% |

Stunning. Applications have almost tripled, while acceptances (and incoming class sizes) have remained constant over 30 years. Notice too that the male-female ratio has gone from 3 to 1 my freshman year (which already represented a decline) to almost 1 to 1 today. Also, it appears that "underrepresented minorities" (African Americans, Native Americans, Latinos, but not Asian Americans or Jews) are no longer underrepresented. And despite the higher ratio of international students, they have the worst ratio of applications to acceptances -- about 3%.