MIT: September 2017 Archives

Paul Gray, president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology from 1980 to 1990 and the man who handed me my college diploma, died today at the age of 85. Gray was the last true MIT nerd to hold the post, possibly the last who ever will. In his years in the MIT administration, Gray managed to improve the undergraduate experience and broaden the base of potential MIT students while preserving the school's distinctive ethos that he had known since his undergraduate days.

Paul Gray, president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology from 1980 to 1990 and the man who handed me my college diploma, died today at the age of 85. Gray was the last true MIT nerd to hold the post, possibly the last who ever will. In his years in the MIT administration, Gray managed to improve the undergraduate experience and broaden the base of potential MIT students while preserving the school's distinctive ethos that he had known since his undergraduate days.

In the 2008 Infinite History interview with Paul Gray tells his life story in his own words (the link leads to a transcript), and what follows is a summary and excerpts that I found interesting.

Gray, the son of an electrical utility technician, started experimenting with electricity and magnetism as a first grader, began building and repairing radios with vacuum tubes at the age of 10, and became an amateur radio operator in high school, building his own equipment. Accepted to RPI, Yale, and MIT, Gray signed up for MIT at the urging of his high school English teacher:

GRAY: ... I was admitted to all three. But MIT was the only one that didn't offer me any money. The other two made it quite easy to go. And I was about to go to Yale, which it offered the most, when I had a conversation with really my first mentor besides my family. And that was my English teacher in high school: had her for four years. Emily Morford. M-O-R-F-O-R-D. And I told her-- she knew where I'd applied, she wrote a reference-- and I told her what my tentative decision was and she took me to the woodshed. And she said, "You can't do that. If you have a chance to go to MIT that's where you should go. It's the best place to study engineering."INTERVIEWER: Now wait a minute, this is the English teacher telling you?

GRAY: The English teacher, English teacher. Who lived long enough to see me elected president here. What, 1950 to 1980, 30 years later. She couldn't come to the inauguration. She was in her 90s and lived in Florida, but she knew about it. She had been an important-- she was perhaps the teacher in high school that I remember the most. And that includes chemistry and physics and biology and mathematics. And it was her influence that pushed me the other way. I went back and the family said, "Well we can manage that. Do it." So that's how it happened.

I can't resist quoting what Gray said about how he learned to write and the disconnect between SAT scores and actual verbal skills:

GRAY: ... I've always enjoyed writing and do a lot of it. And maybe that's part of it because she taught writing, she taught the English language, the way it should have been taught. You know we diagrammed sentences, we worked on paragraph structure, the whole nine yards. And I came out of high school I think being a pretty good writer. And it paid off in later years here, still pays off.INTERVIEWER: Do you think many MIT students can diagram a sentence today?

GRAY: No, too many of them can't really create a sensible sentence, let alone a paragraph. It's astonishing to me. I mean MIT students come here with an average verbal school of something like 750. But still most of them are abominable writers. Not all-- I mean, some are very skillful. Some have learned the craft. But a great many of them come here needing a boost in their writing, which they get.

Gray was the last of a series of five presidents with connections to the Institute prior to taking office, and one of three who had attended the university as undergraduates. Gray's two immediate successors had no prior connection to the Institute; the current president, L. Rafael Reif, joined the MIT electrical engineering faculty in 1980 and has been at MIT ever since.

As an undergraduate, Gray found a home away from home and lifelong friends in an MIT fraternity, Phi Sigma Kappa:

During the summer, in those days, freshmen got visited by fraternity students because when you arrived here, you had to make a choice between whether you were going to live in a dormitory or live in a fraternity, pledge a fraternity. And I had a visit that summer from two students, both of them living in New Jersey, and I said, "No, I'm not going to rush week. I'm going to live in the dormitory." I already had an assignment in East campus which was then all single rooms. And I lived there through, about through Thanksgiving, but found it was intensely lonely, partly because all the folks around me in that dormitory were GIs who had come back from World War II. You know, the largest class ever to graduate from MIT was the class of 1950, because it swept up all the guys who had had their education interrupted in the early '40s. And the GIs who returned were very single-minded about their studies. They were not involved in any social life or other activities that eighteen-year-olds would be involved in. And I just felt isolated.So as it happened, the two students who had visited me in the summer showed up again one evening and visited me at the dormitory and said, "Why don't you come over and have dinner?" Well I did. And that opened my eyes to a very different style of living at MIT. To live with 28 other people in a four-story house on Commonwealth Avenue. And so I moved into the house in December and lived there for the next three-plus years. Three-and-a-half-plus years. And that was also an important learning and living experience for me because I was an only child. I had only two cousins, one on each side of the family, saw them seldom and really had grown up without-- had neighborhood friends, to be sure, but their interests were different from mine-- had never had an association with other people my age whose interests overlapped with mine. And I had a role there eventually in governance of the place, as well as most people did, and it was a great experience....

The living members of my pledge class, of which there are about five or six, we get together every September for a clam bake at one or another's house. This year it's at our place.

Gray received his S. B. in Electrical Engineering in 1954, his S. M. the following year, and then decided he'd "had it" and was leaving MIT, never to return.

After two years in military service, which involved teaching GIs in the use and maintenance of listening devices, Gray came back to MIT in 1957 and received his Sc. D. in 1960. Gray's doctoral research involved developing compound semiconductor materials for new applications, in which he had to develop the techniques to make the materials himself in an induction furnace: "Nobody to teach me the techniques, to how to do this in a way that would produce crystalline materials. It was a real challenge."

During his military service and doctoral studies, Gray discovered that he loved teaching. As a new faculty member, Gray became a leader in redirecting the electrical engineering curriculum from vacuum tubes to semiconductors. In the late 1960s, Gray was asked to move into higher positions of administrative leadership, serving as an associate dean of student affairs, associate provost, and dean of engineering. When Jerry Wiesner became MIT president, he asked Gray to become his deputy as chancellor of the Institute.

I'll let you read for yourselves Gray's role in the creation of the Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program and his description of the pragmatic and peaceful process that led MIT to reach out deliberately to encourage members of minority groups and women to apply. (Prior to 1968, MIT did no recruiting at all and accepted about 25% of applicants.) I'll close by focusing on a couple of anecdotes that epitomize Gray's leadership as president.

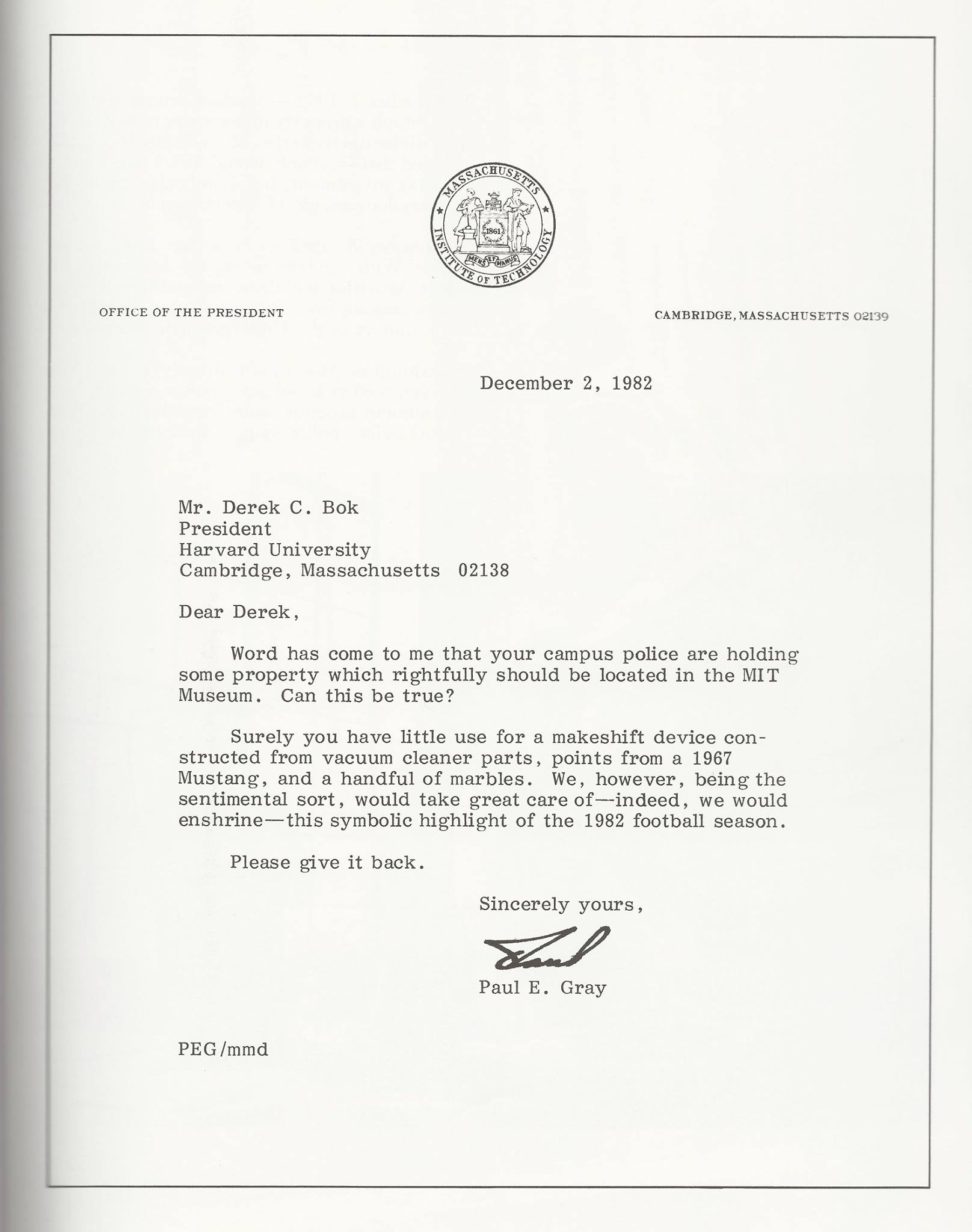

In the fall of 1982, MIT's chapter of Delta Kappa Epsilon (DKE) planted and inflated a weather balloon marked MIT in the middle of Harvard Stadium during the Harvard-Yale game, a stunt regarded as the greatest hack in MIT's history:

Dear Derek,Word has come to me that your campus police are holding some property which rightfully should be located in the MIT Museum. Can this be true?

Surely you have little use for a makeshift device constructed from vacuum cleaner parts, points from a 1967 Mustang, and a handful of marbles. We, however, being the sentimental sort, would take great care of -- indeed, we would enshrine -- this symbolic highlight of the 1982 football season.

Please give it back.

Sincerely yours,

Paul E. Gray

A few years later, enrollment in Course VI, the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, as the first generation of students who had begun working with computers in high school arrived on campus. MIT had always allowed students to choose a major without jumping through any additional hoops, but the crowding in Course VI led to talk of entrance restrictions. The crunch led Gray back to the classroom to "shame [his] colleagues":

In the middle 80s, the enrollment in electrical engineering and computer science was exploding. And it started out the decade at about 200 per class, 200, 250 per class. And by 1985 it was up to 350. And there was concern that if the trend line continued, it was going to go past 400. It was more than the department could staff and manage. And what's more it beggared all the other departments, who said, "Where are my students? They're all in EE!"And the department at that point was desperate to get more people to teach sections. And a number of folks who were faculty members of EECS, but were also laboratory heads, were saying, "Gee, I just don't have time for that." So, I figured if I showed up and taught two sections for a couple of semesters, some other people might catch on. And they did. It made some difference.

The trend line began to turn as other departments began to offer classes in computer programming, as applied to each discipline. "That drained off some of the students that otherwise would have thought they had to be in Course VI in order to learn to be computer scientists."

Those of us who were at MIT in the 1980s were blessed to be there under a leader who remembered what it was like to be in our shoes, who understood the value of the residential community (be it fraternity, independent living group, or dorm entry) as home-away-from-home, and who, without embracing political correctness or institutional fascism, navigated societal change with MIT engineering pragmatism. May his memory be a blessing.