Tulsa History: May 2010 Archives

My apologies for the lapse since my last post. I've been writing, but it's all technical stuff for the gig that pays most of the bills.

While I was at the Coffee House on Cherry Street cranking away on that technical documentation, a customer at the next table, a gentleman named Cecil Cloud, said hello, identified himself as a BatesLine reader, and mentioned a post here about historic maps.

Cecil showed me an amazing collection of U. S. Geological Survey maps of Indian Territory and Oklahoma, online at the University of Texas Perry Castañeda Library Map Collection. Most of the maps predate statehood.

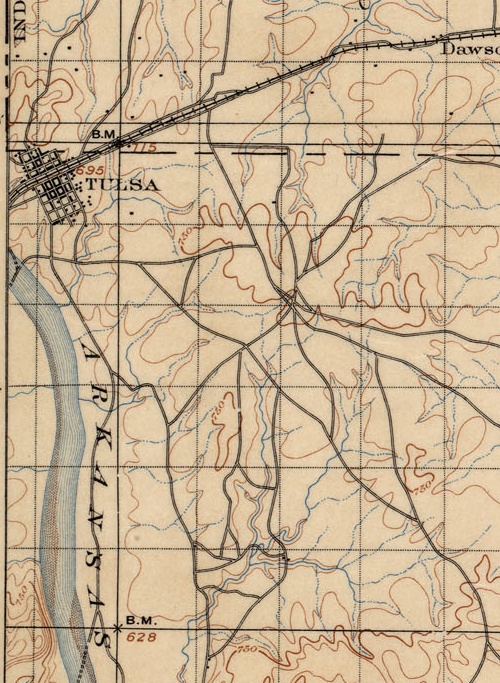

Take a look at this map showing Tulsa as part of the Claremore quadrangle, 1897. What's fascinating is that this is before the Dawes Commission, before land was allotted in quarter-sections to enrolled tribal members, and therefore before the familiar grid of section line roads was established. The townships, ranges, and sections were established, and are shown on the map as a reference grid, making it possible to pinpoint old locations with respect to the present day arterial grid. But the roads on these pre-1900 maps show a network of roads that follows the land, connecting settlements as directly as the terrain will allow.

Here's the section of the map covering what is now midtown and downtown Tulsa.

The grid of early day Tulsa is there, laid out parallel and perpendicular to the Frisco tracks which gave birth to the town. But the grid extends only from modern day Cameron St to 4th St, Cheyenne Ave to Cincinnati Ave. Beyond that, notice the hub of trails just east of present day 21st and Harvard, probably close to the high point that was more recently occupied by a water tower (just east of 21st and Louisville).

Notice too the creeks and streams, long before they were turned into underground storm sewers or rerouted into concrete channels. It's interesting, too, to see the locations of fords and ferries.

Here's an interesting contrast in the neighboring quad to the north, covering Washington, Nowata, and northern Rogers counties:

In just 16 years, the network of trails has been mostly replaced with a grid of section line roads, new towns have been established, and every few miles there's a school. Note the electric railway linking Bartlesville, Tuxedo, and Dewey.

More amazement at the PCL online archive:

1:250,000 USGS maps, including Tulsa maps from 1947 and 1967, covering all of Oklahoma northeast of Jenks. Note that the 1947 city map of Tulsa shows the Tulsa County Fairgrounds within the Tulsa city limits. The 1947 topo map shows the Union Electric Railway connecting Nowata and Coffeyville.

McGraw Electric Railway Manual Maps, 1913: Streetcar maps from nearly everywhere except Oklahoma, including Joplin, Little Rock, Dallas, Fort Worth, San Antonio, and Brooklyn.

Reader Sue Snider was kind enough to send along a bit of letterhead from the Oklahoma Hotel, something she found while sorting through things after a move.

OKLAHOMA HOTEL

EUROPEAN

R. E. DRENNAN, PROPRIETOR

MODERN IN EVERY PARTICULAR

COURTESY AND SERVICE

There's no address on it, but it may be the "New Oklahoma Hotel" identified on the 1939 and 1962 Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps on the southeast corner of 2nd and Cincinnati, on the second and third floors, above the Oklahoma Tire and Supply Company (better known to Sooner boomers as OTASCO). This is the northwest corner of Block 107 of Tulsa's original townsite. Thanks to reader Mark Sanders, we know that the 1947 Polk City Directory lists the New Oklahoma Hotel at this location. The 1957 Polk directory doesn't show a hotel at that location, so Ms. Snider's estimate of a date in the 1940s is probably accurate.

In 1960, it was the most populous downtown block with 199 residents. Today it's a surface parking lot serving the Performing Arts Center and Tulsa's new City Hall.

I haven't been able to find out anything about proprietor R. E. Drennan, but I see a few current Tulsa listings for the Drennan name, so perhaps there's a connection.

This sort of thing never happens, right? Never, ever would a secretive group of private business leaders direct the redevelopment decisions of public agencies from behind the scenes. And if they did, well, we just have to trust that these business leaders know far more about urban development than the unwashed masses, as is readily apparent by the wealth they accumulated in completely unrelated fields of endeavor, right? We just have to trust that they have the best interests of the city at heart.

The OKC History Blog has an entry about a group of Oklahoma City business executives called Metro Action Planners and their efforts (of questionable legality) in the late 1970s to implement architect I. M. Pei's plan for downtown redevelopment. The story begins with Pei's return visit in 1976:

His summons to appear came from a new, informal group of downtown Oklahoma City business leaders assembled by the Chamber of Commerce to expedite implementation of his plans for the area.The group - Metro Action Planners - was led by Southwestern Bell President John Parsons. The group had no office, no phone number, and no mailing list. And no vice presidents or directors were allowed.

Its membership was limited to CEOs, presidents and downtown property owners, and those who belonged included Charles Vose, president of First National Bank and Edward L. Gaylord, publisher of The Daily Oklahoman.

Behind the scenes, the group picked which retail developer would get a shot at building a planned indoor shopping mall:

In April [1977], the Urban Renewal Authority sought new proposals and got them from a local man, Bill Peterson, Dallas-based developer Vincent Carrozza, who estimated he could get the project done in six to 10 years, another outside developer, Starrett-Landmark, and Cadillac Fairview. (5)While Carrozza, in particular, had no doubts about his project's future success, Cadillac Fairview's proposal was much more reserved in that regard.

The latter's proposal cautioned that there was "absolutely no certainty at this time that sufficient department store interest can be committed to ensure that the major Galleria retail can proceed in the near future."

But, Carrozza enchanted Metro Action Planners. The group, in fact, committed itself to raise $1.6 million needed to create a limited partnership with the developer to get the project going.

Before the end of April, 1978, Carrozza had his deal with local leaders.

Then everything unraveled when the developer asked for a favor from an official who, evidently, wasn't part of the in-crowd:

Oklahoma's attorney general launched a probe in August of 1980 to determine whether Carrozza, urban renewal and Metro Action Planners had restrained trade by creating an informal building moratorium downtown to enhance possibilities that the Galleria project would be successful.The Metro Action Planners, it had turned out, had approved a moratorium on downtown building in October 1978. The following year, Carrozza had contacted an Urban Renewal commissioner, asking him to seek a second moratorium from the group. At the time, Carrozza was finding it difficult to find financing for a second office tower he was building on the Galleria site.

The commissioner - Stanton L. Young - declined to carry out Carrozza's request, and was not implicated of any wrong-doing.

Neither, curiously, was anyone else.

But while the attorney general's investigation went nowhere, the damage to this super-powerful group of downtown leaders had been done.

Metro Action Planners abruptly disappeared from the downtown redevelopment scene.

So much for corporate commitment to the free market. This shadowy group choked off downtown development to clear the path for their favored developer, who (by the way) never completed his project. The land -- most of a 2 x 2 superblock -- continues to sit mostly empty. The new downtown library was built on the northwest corner of the site.

But I'm sure this situation was peculiar to Oklahoma City, and powerful, private groups have never steered the actions of Tulsa's urban renewal agency, and if they did, I'm sure it was for our own good.

Some time ago, I wrote a blog post urging the stewards of the Beryl Ford Collection to post the collection on Flickr, so as to invite public participation in collecting data about people, places, and times depicted in photos and ephemera from Tulsa history. A couple of months later, I learned that Flickr has a special program specifically for archives like the Beryl Ford Collection. It's called Flickr Commons, and it's being used by the likes of the Library of Congress, the Smithsonian Institution, and national archives in the US, UK, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Scotland, and Texas.

Some time ago, I wrote a blog post urging the stewards of the Beryl Ford Collection to post the collection on Flickr, so as to invite public participation in collecting data about people, places, and times depicted in photos and ephemera from Tulsa history. A couple of months later, I learned that Flickr has a special program specifically for archives like the Beryl Ford Collection. It's called Flickr Commons, and it's being used by the likes of the Library of Congress, the Smithsonian Institution, and national archives in the US, UK, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Scotland, and Texas.

Smaller institutions are participating as well: The Bergen Public Library, the Jewish Historical Society of the Upper Midwest, and the Upper Arlington (Ohio) History collection. Tulsa's Beryl Ford Collection would fit right in.

The institutions are participating in Flickr Commons to make their collections more widely available and to extend their ability to identify what they have, using Flickr's built-in tools to collect comments, notes, and geographical and chronological metadata about each photo.

The key goals of The Commons on Flickr are to firstly show you hidden treasures in the world's public photography archives, and secondly to show how your input and knowledge can help make these collections even richer.

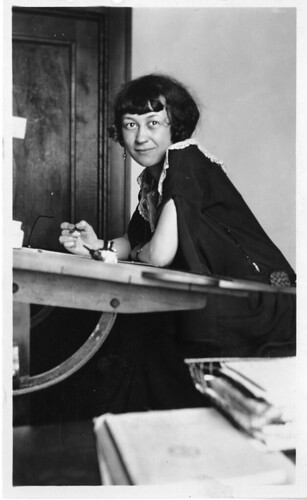

Today I found a great example of how this works. The Smithsonian Institution is publishing a series of photos called "Women in Science." One of the photos is of Elizabeth Sabin Goodwin. The photo's description:

The Flickr community is invited to assist in the identification of Ms. Goodwin.

And so they have. Within a month or so, someone found her 1924 wedding announcement in the Washington Post's online archives. A mention of her high school and age led to her photo in the Central High School yearbook, and later obituaries for her father and husband turned up. Recently, her granddaughter came across the photo and provided more information about Elizabeth Sabin Goodwin, and why this artist would have been included in the Science Service's collection -- she was an illustrator for a science magazine.

More here about E. S. Goodwin on indicommons, a blog devoted to interesting finds in The Commons on Flickr.

Here's another example of Web 2.0 collaboration to identify historic photos: Amateur history detectives discovered that the surname of this woman of science had been mis-transcribed from handwriting -- "Gans" was misread as "Gaus."

MORE:

Still plenty of mystery women of science to be identified: Who is J. M. Deming? Or Miss W. Dennis?

Indicommons brings together photos of the 1893 Chicago World's Fair from various Commons collections. There's a Google Earth overlay of Columbian Exposition photos, too.

The Texas State Archives debuts with architectural drawings of state park facilities built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s.