Tulsa History: May 2011 Archives

On the night of May 31, 1921, a white mob descended upon Tulsa's African-American district, known as Greenwood after its principal avenue, looting, shooting, and firebombing into the following day. The attack killed hundreds and left thousands wounded and homeless and destroyed dozens of African-American businesses and churches.

Once hushed up, the attack known as the Tulsa Race Riot has received an increasing amount of public attention in recent decades. I have half a shelf taken up with books on the topic, and I will leave that history to others who have told it far better than I could ever hope to do.

What is often overlooked is the triumph and tragedy that followed the riot. The story of Tulsa's Greenwood District did not end in 1921, and over the last few years I've taken it upon myself to learn that story and attempt to bring it to a broader audience.

After the riot, there was an attempt by the city's white leaders to keep Greenwood from being rebuilt. The City Commission passed an ordinance extending the fire limits to include Greenwood, prohibiting frame houses from being rebuilt. The idea was to designate the district for industrial use and resettle blacks to a new place further away from downtown, outside the city limits.African-American attorneys won an injunction against the new fire ordinance; the court decreed that it constituted a violation of the Fourth Amendment, a taking of property without due process. The injunction opened the door for Greenwood residents to rebuild.

They did it themselves, without insurance funds (most policies had a riot exclusion) or any other significant outside aid....

The Greenwood district flourished well into the 1950s. In 1938, businessmen formed the Greenwood Chamber of Commerce. A 1942 directory lists 242 businesses, including over 50 eateries, 38 grocers, a half dozen clothing stores, plus florists, physicians, attorneys, furriers, bakeries, theaters, and jewelers -- more than before the riot 21 years earlier. The 1957 city directory reveals a similar level of commercial activity in Greenwood....

The rebuilding, subsequent renaissance, and final removal of Greenwood are documented by aerial and street photos, land records, fire insurance maps, newspaper stories, street directories, and census data.

All that raw data is fleshed out in the memories of those who lived through those times. Some of those stories have been captured in books like They Came Searching by Eddie Faye Gates and Black Wall Street by Hannibal Johnson.

Here are a couple of reminiscences included by Gates in her book that clearly connect the term Black Wall Street to the post-riot, rebuilt Greenwood:

"They just were not going to be kept down. They were determined not to give up. So they rebuilt Greenwood and it was just wonderful. It became known as The Black Wall Street of America."

- Eunice Jackson"The North Tulsa after the riot was even more impressive than before the riot. That is when Greenwood became known as 'The Black Wall Street of America.'"

- Juanita Alexander Lewis Hopkins

But then came the planners:

"Slum clearance," as a cure for Greenwood's ills, had been discussed for years, but in 1967, Tulsa was accepted into the Federal Model Cities program.Model Cities was not just an ordinary urban renewal program. It was intended to be an improvement over the old method of bulldozing depressed neighborhoods. The Federal government provided four dollars for every dollar of local funding, and the plan involved advisory councils of local residents and attempted to address education, economic development, and health care as well as dilapidated buildings.

For all the frills, Model Cities was still primarily an urban removal program: Save the neighborhood by destroying it. Homes and businesses were cleared for the construction of I-244 and US 75 and for assemblage into larger tracts that might attract developers. Displaced blacks moved north, into neighborhoods that had been built in the '50s for working class whites.

Only the determination of a few community leaders saved a cluster of buildings in Deep Greenwood -- but these buildings are isolated from any residential area, cut off from community.

In April 1970, as Tulsa's Model Cities urban renewal program was beginning to demolish homes, Mabel Little, whose new home was burned down in the 1921 attack, told the Tulsa City Commission [from the April 11, 1970, Tulsa Tribune]:

"You destroyed everything we had. I was here in it, and the people are suffering more now than they did then."

Years later, Jobie Holderness reflected on the spiritual damage done by urban renewal:

"Urban renewal not only took away our property, but something else more important -- our black unity, our pride, our sense of achievement and history. We need to regain that. Our youth missed that and that is why they are lost today, that is why they are in 'limbo' now."

Here's my talk on this topic at Ignite Tulsa in 2009:

And here are links to previous BatesLine entries about Greenwood's renaissance:

The Greenwood Gap Theory: My June 2007 Urban Tulsa Weekly column on the popular misconception, abetted by the second destruction due to urban renewal, that Greenwood was not rebuilt after the 1921 massacre.

Notes on the sources documenting Greenwood's post-riot renaissance: My response to OSU-Tulsa history professor J. S. Maloy, who disbelieved my account of the post-massacre revival of Greenwood.

Greenwood 1957: A summary of commercial activity in Greenwood, based on the 1957 Polk street directory of Tulsa.

Greenwood's streetcar: The Sand Springs Railroad (includes photos)

The rise and fall of Greenwood (includes high res 1951 aerial photo of Deep Greenwood)

Tulsa 1957 restaurants: A KML (Google Maps) file locating restaurants listed in the 1957 street and phone directories, including many that lined Greenwood Ave.

Film of Oklahoma's 1920's black communities

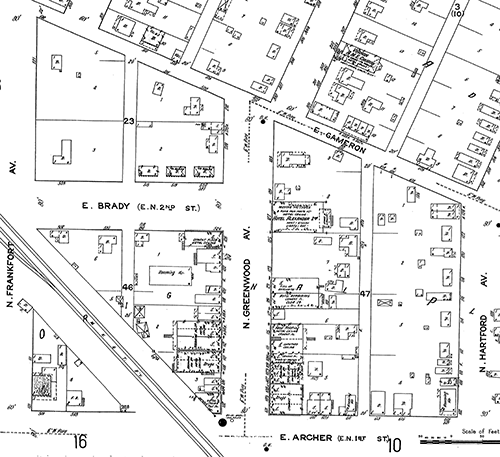

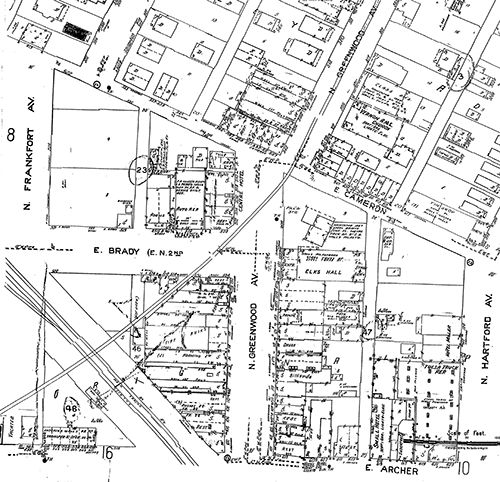

Finally, here at a glance are three Sanborn maps from 1915, 1939, and 1962, showing Deep Greenwood over the decades:

Sanborn Map: Deep Greenwood in 1915

Sanborn Map: Deep Greenwood in 1939

Sanborn Map: Deep Greenwood in 1962

FOLLOW-UPS:

- Tate Brady, the Klan, and the attack on Greenwood

- Brenda Terry (Flash Terry's daughter) on Greenwood in the '40s and '50s

- Films of Greenwood post-riot and Oklahoma's African-American communities in the 1920s (the Solomon Sir Jones collection)

- Smithsonian Channel mangles Greenwood history

- Greenwood demolition in 1967 for expressway construction: "There is no Negro business district anymore"

- Greenwood Gap Theory: Tulsa's Green Book places weren't destroyed in 1921

- Segregation by Design: Greenwood and I-244: Adam Paul Susaneck's stark, graphical depiction showing the destruction wrought by the path of I-244 through Greenwood and neighboring districts, and the Guardian article on plans to remove I-244

UPDATE 2020/06/03: Since this article has become a central repository of links to my work on Greenwood, I'm updating the title, which was originally "The 1921 Tulsa Race Riot and the 90 years that followed." I've also changed the first paragraph to be less date-specific. It originally read: "Today is the 90th anniversary of a white mob's attack on Tulsa's African-American district, known as Greenwood after its principal avenue. The attack, which began the evening of May 31, 1921, killed hundreds and left thousands wounded and homeless." I also changed the phrase "over the last 30 years" to "in recent decades."