Tulsa History: October 2019 Archives

Greenwood Ave., north of Easton St., looking north along Sand Springs Railroad interurban tracks toward intersection with Greenwood Pl. and the Del Rio Hotel, which was listed in the 1954-1956 editions of the Green Book.

Mike McUsic, a historical researcher on the topic of the Green Book, the segregation-era travel guide for African-American tourists, will be leading walking tours of the Green Book locations in Tulsa's Greenwood District on November 16 and 23 at 11:00 am. The tour is free (donation requested), with tickets available via Eventbrite.

Mr. McUsic has developed the Green Book Travelers HistoryPin site, locating 1,900 Green Book locations across the country, with names, descriptions, and historic and present-day photos. This link will take you to locations specific to Greenwood.

MORE: Here's a collection of links to BatesLine articles and other resources about Greenwood and Black Wall Street. Earlier this year, I wrote about the Green Book as additional evidence of Greenwood's post-1921 rebuilding and listed the Tulsa Green Book sites still standing.

In March 1994, national radio commentator Paul Harvey, whose thrice-daily broadcasts were carried on over 1400 stations nationwide on the ABC radio network, reaching an audience in the tens of millions, returned to Tulsa to speak at a Salvation Army benefit. After his visit, he spoke on the air about his bittersweet memories of his hometown and his neighborhood and how Tulsa had changed since. I first came across a transcript of his comments back in 2011.

In March 1994, national radio commentator Paul Harvey, whose thrice-daily broadcasts were carried on over 1400 stations nationwide on the ABC radio network, reaching an audience in the tens of millions, returned to Tulsa to speak at a Salvation Army benefit. After his visit, he spoke on the air about his bittersweet memories of his hometown and his neighborhood and how Tulsa had changed since. I first came across a transcript of his comments back in 2011.

Recently, I dug through old Tulsa Central High School yearbooks to find photos of some of the people he mentioned. With the demolition of his childhood home and what's left of his childhood neighborhood a topic of discussion at a public meeting tomorrow night, it seemed like a good time to revisit Paul's memories of his old stomping grounds.

Over my shoulder a backward glance.The world began for Paul Harvey in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Ever since I have made tomorrow my favorite day, I've been uncomfortable looking back.

My recent revisit reminded me why. The Tulsa I knew isn't there anymore. And the memories of once-upon-a time are more bitter than sweet.

Of the lawman father I barely knew.

The widowed mother who worked too hard and died too soon. And my sister Frances.

Tulsa was three graves side-by-side.

Recently I came face-to-face with the place where a small Paul Harvey's mother buttoned his britches to his shirt to keep them up and it down.

Tulsa is a copper penny which a small boy from East Fifth Place placed on a trolley track to see it mashed flat.

It's a slingshot made from a forked branch aimed at a living bird, and the bird died, and he cried, and he is still crying.

That little lad was seven when he snapped a rubber band against the neck of the neighbor girl, and pretty Ethel Mae Hazelton ran home crying, and he, lonely, had wanted only to get her to notice him.

Somehow he blamed Tulsa for the war which took his best friend, Harold Collis...

And classmate Fred Markgraf...

And never gave them back.

In Tulsa, Oklahoma, he learned the wages of sin smoking grapevine behind the garage and getting a mouthful of ants.

Longfellow Elementary school is closed now; dark.

Tulsa High is a business building.

The old house at 1014 is in mourning for the Tulsa that isn't there anymore.

It was in that house that a well-meaning mother arranged a surprise birthday party when he was sixteen; invited his school friends, including delicate Mary Betty French without whom he was sure he could not live.

He hated that party for revealing to her and to them his house, so much more modest than theirs.

Tulsa is where the true love of his life waved goodbye to the uniform that climbed aboard a troop train.

She was there waiting when he got back but they could not wait to say goodbye to Tulsa.

Tulsa was watermelon picnics in the backyard and a small Paul blowing taps on his Boy Scout bugle over the fresh grave of a dead kitten.

Tulsa, Oklahoma, used to be the fragrance of honeysuckle on the trellis behind the porch swing.

Mowing for a quarter neighbors' lawns that seemed then so enormous.

Only Tulsa's delicious tap water is as it was.

That and the schoolteachers...

Miss Harp and Miss Smith and Isabelle Ronan. These I am assured are still there somewhere--reincarnated.

In a sleek jet departing Tulsa's vast Spartan Airport at midnight, I closed my eyes and remembered...

When Spartan was a sod strip...

And a crowd gathered...

And a great tin goose landed...

And Slim Lindbergh got out...

And a boy, age nine, was pressing against the restraining ropes daring to foretaste fame--and falling in love with the sky.

No...

The Tulsa I knew isn't there anymore. But it's all right.

A new Tulsa is.

I'll not be afraid to go home again.

I have made friends with the ghosts.

A recording of this commentary hasn't turned up, but his famous speech, "So God Made a Farmer," delivered to a Future Farmers of America conference in 1978 and made into a celebrated Dodge Ram Trucks Super Bowl ad in 2013, will give you a good idea of his pacing and delivery. Those of us who listened to him every day for decades will have no trouble hearing his voice as they read the words above.

Some notes about the people and places Paul Harvey mentioned:

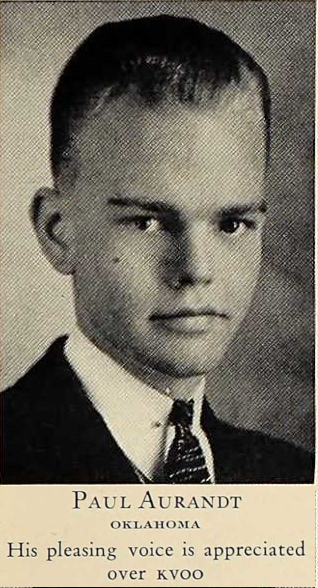

The photos are senior portraits from the Tulsa Central High School Tom-Tom -- the school's yearbook. Ethel Mae Mazelton, Harold Collis, and Mary Betty French were Class of 1935. Ethel Mae lived two doors east of the Aurandts at 1024 E. 5th Place, and went on to be named Miss Kendallabrum at the University of Tulsa in 1936. Fred Markgraf and Paul Harvey Aurandt were both Class of 1936; Markgraf was senior class president. The photo of long-time speech and English teacher Isabelle Ronan (credited by both Paul Harvey and Tony Randall for starting them in their careers) was from the 1934 yearbook.

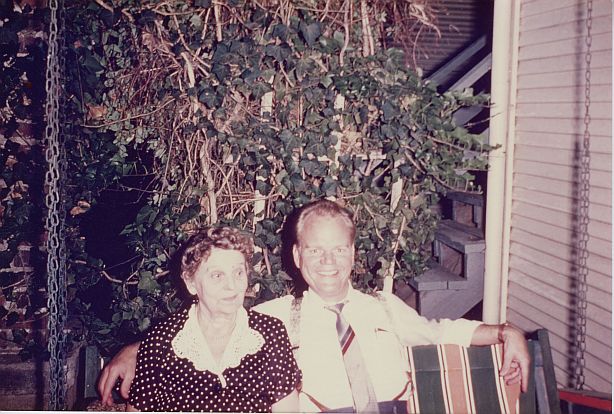

When Paul was three, on December 18, 1921, his policeman father was shot by criminals attempting to rob him and a colleague; Officer Harry Harrison Aurandt died two days later. Paul's mother, Anna Dagmar Aurandt, lived the rest of her life in that house, renting out some of the rooms to pay the bills. Here she is on that porch swing with Paul in the late '50s, and you'll notice the vine-covered trellis behind them.

The tracks of the Tulsa Street Railway ran east out of downtown on 3rd Street, forked north and south on Madison Avenue; the southern branch turned east on 5th Place, past the Aurandts' house at 1014 E. 5th Place, and south on Quincy, terminating at 15th Street. In 1922, the Bellview-Owen Park line, as it was called, ran every 10 minutes from 6 am to 11 pm, so there would have been plenty of opportunities for a mischievous kid to put a penny on the track. I imagine the screech of the trolley making the 90 degree turn at Madison would have been a familiar sound in the Aurandt home.

Longfellow School was on the northwest corner of 6th and Peoria. Built to H. O. McClure's "Unit Plan," the school consisted of a series of connected two-classroom buildings surrounding a courtyard. I can't find a photo of it, but Jack Frank of Tulsa Films has a clip of a 1960s news story about a Longfellow School crossing guard, which provides a good look all around the 6th and Peoria intersection. Longfellow was still there, but closed, when Paul Harvey returned home in 1994. It was sold to IHCRC Realty Corp in 1996, and the school was demolished and replaced with the Indian Health Care Resource Center. The shell of the old Central High School building still stands downtown, converted in 1985 to offices for Public Service Company of Oklahoma.

Paul Harvey was slightly mistaken about the location of Lindbergh's Tulsa landing. On September 30, 1927, during that year's International Petroleum Exposition, Lindbergh flew the Spirit of St. Louis into McIntyre Airport, southeast of Admiral and Sheridan, a private airport founded by New Zealand World War I veteran Duncan McIntyre. The aviator's arrow atop Reservoir Hill originally pointed to McIntyre Field. In 1927, Tulsa didn't yet have a municipal airport, but Lindbergh's visit, part of the Guggenheim Tour, provided the inspiration for Tulsa leaders to get one built. It was alongside the new municipal airport that W. G. Skelly built the Spartan Aircraft factory and Spartan School of Aeronautics, about a year later. It's understandable that Harvey would conflate the two.

McIntyre Airport, September 30, 1927. (L to R) Lt. A.C. Strickland (Lindbergh's trainer), Col. Charles A. Lindbergh, Mayor Herman F. Newblock, and Lt. Arthur Goebel. McIntyre Airport was Tulsa's first commercial airport, located at the southeast corner of Admiral Place (aka Hwy 66) and Sheridan Street. Lindbergh always carried his leather flight helmet with him (left hand in photo). The medal on Mayor Newblock's lapel was given to him by Charles Lindbergh. The medal says Lucky Lindy, New York to Paris. Accession #A0045. The Beryl Ford Collection/Rotary Club of Tulsa, Tulsa City-County Library and Tulsa Historical Society.

McIntyre Airport, September 30, 1927. (L to R) Lt. A.C. Strickland (Lindbergh's trainer), Col. Charles A. Lindbergh, Mayor Herman F. Newblock, and Lt. Arthur Goebel. McIntyre Airport was Tulsa's first commercial airport, located at the southeast corner of Admiral Place (aka Hwy 66) and Sheridan Street. Lindbergh always carried his leather flight helmet with him (left hand in photo). The medal on Mayor Newblock's lapel was given to him by Charles Lindbergh. The medal says Lucky Lindy, New York to Paris. Accession #A0045. The Beryl Ford Collection/Rotary Club of Tulsa, Tulsa City-County Library and Tulsa Historical Society.

While looking for something else in the Oklahoma Historical Society's online newspaper database, I came across this startling headline atop the April 17, 1921, edition of the Tulsa Sunday World:

PRICELESS PAINTING RECOVERED HERE

Beligum Reclaims Ancient Million-Dollar Work of Old Master

Bristow Tool Dresser

Had Ruebens' Work,

'Descent From Cross'

The story states that R. L. Bolin was with the American Expeditionary Forces mounted police in Europe. He bought the Rubens painting in the town of Baute, Germany: "... the canvas in an obscure and dingy art shop attracted Bolin's eye, and he bought it for a mere song." He cut the canvas from the frame, rolled it up with other paintings, and after the armistice he returned to Tulsa. He took this painting (with two others) to Lester W. Wetzel of the Tulsa Art Store at 620 S. Boston, who restored and reframed it and hung it on the north wall of the store. There it stayed for eight months. No one suspected it was anything but a high quality reproduction.

Bolin left Tulsa to become a tool dresser's apprentice near Bristow. He needed some cash, so he asked Wetzel to sell the three paintings he had left with him, but no one was interested. At some point, he began to think they might have been among those works of art stolen by the Kaiser's forces. Through his stepmother, a magazine writer, Bolin got in touch with Charles W. Thurmond, whom the story describes as a finder of lost art works, including the painting, "Head of Peter," which he recovered from an express office and returned to the Vatican.

The story says that Thurmond had been hired by the Belgian government to find this painting. When he received the letter, he caught the next train from New York, examined the painting, declared it genuine, stayed in the store overnight to guard it, then returned to New York the next day with Bolin and the painting.

The story was picked up by United News wire service, and it appeared three days later, on April 20, 1921, in The Dalles (Oregon) Daily Chronicle, with some changed details. The Tulsa World story gave the date of the painting as 1412; the Daily Chronicle story said 1692, and corrected the spelling of the painter's name, which the World misspelled as Reubens.

The New York Times had the story in the Monday, April 18, 1921, edition, datelined Tulsa, April 16 -- the day that Bolin, Thurmond, and the painting set out for New York. The Times asked an art dealer about the chances that the painting was genuine:

Sir Joseph Duveen of Duveen Brothers, 720 Fifth Avenue, said that the masterpiece of the famous painter, Peter Paul Rubens, was still in the Antwerp Museum when he was in Belgium a few months ago. The report that the painting had disappeared has no foundation, Sir Joseph said. "The Descent from the Cross" was painted in 1612 and not in 1412, Sir Joseph remarked, and added that just as the date of the painting was incorrect in the Tulsa dispatch, so were other statements in it.It was remarked by one authority on paintings that frequent reports have been received of the existince in different parts of this country of the originals of famous paintings, when as a matter of fact they were only reproductions.

I haven't yet found any follow-up stories that would indicate what happened with Bolin, Thurmond, and the painting. There was a long-time Bolin Ford dealership in Bristow, with the catchy slogan, "Rollin' with Bolin," but I don't know whether there is a connection with the tool dresser's apprentice.

In hindsight, it seems like a story that was "too good to check." A story about an ordinary Oklahoma doughboy, an art connoisseur from New York City, and a stolen masterpiece would sell papers in a booming oil metropolis with pretensions of sophistication. To be honest, I started to write this up as if a Rubens painting really had taken a holiday in Tulsa, but it occurred to me that if that had been the case, it would have made the papers elsewhere.

According to Wikipedia, Napoleon stole "Descent from the Cross" from the cathedral in Antwerp and had it installed in the Louvre, but it was returned after Napoleon's final defeat. There's a possible discrepancy in the New York Times report as well: Sir Joseph Duveen says he saw the painting in the Antwerp Museum, but "Descent from the Cross" was installed in the Cathedral of Our Lady in Antwerp, part of a triptych. According to the cathedral's website, the central panel is 421 cm x 311 cm, or about 13 feet tall by 10 feet wide, with two side panels that are each the same height and half the width. Like most triptychs, it was painted on a wooden panel, which would have been awkward for Mr. Bolin to roll up for easy carrying. (Even if it had been canvas, it would have been like toting around a roll of carpet.)

According to the website of the Cathedral

How might World reporter Faith Hieronymus have fact-checked Thurmond's story? For a start, the public library or the college library likely had an art encyclopedia that would have the dates of Rubens' career -- as well as the correct spelling of the artist's name. No internet back then, and long-distance phone calls were a challenge, but a telegram to a known art dealer in New York might have confirmed Mr. Thurmond's identity as an art detective. A telegram to a wire service correspondent in Belgium could have been used to confirm that the painting was actually missing. But deadlines are deadlines, and I imagine there was a great deal of buzz around town about the painting, and an editor anxious to exploit the public's curiosity.

It's a good reminder, when mining newspapers for history, to separate the facts of which the reporter had direct knowledge from the claims made by the people she interviewed and from her own speculation and wishful thinking.