Greenwood Category

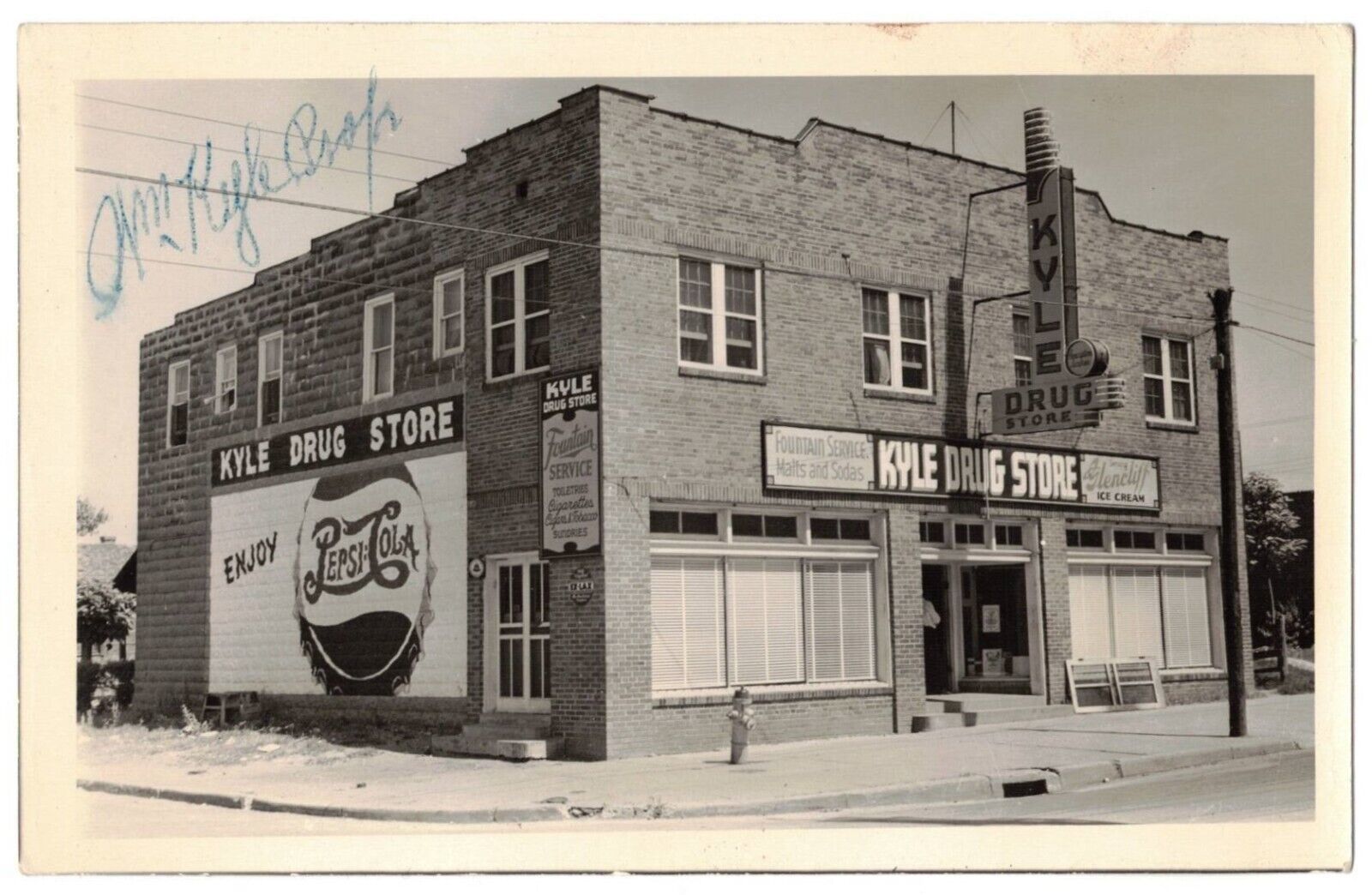

This is the story of a building in Tulsa's Greenwood District that rose from the ashes of the Tulsa Race Massacre, housed a successful pharmacy, became a beloved malt shop, served briefly as a neighborhood co-op grocery, saw its share of burglaries, robberies, and violence, suffered an ignominious old age, and finished its life as a location in a beloved cult film based on a book by a local author, before its final destruction at the hands of city officials, backed by federal funds, after a mere six decades of existence.

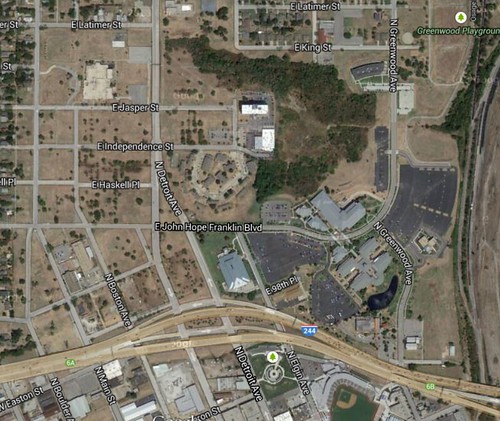

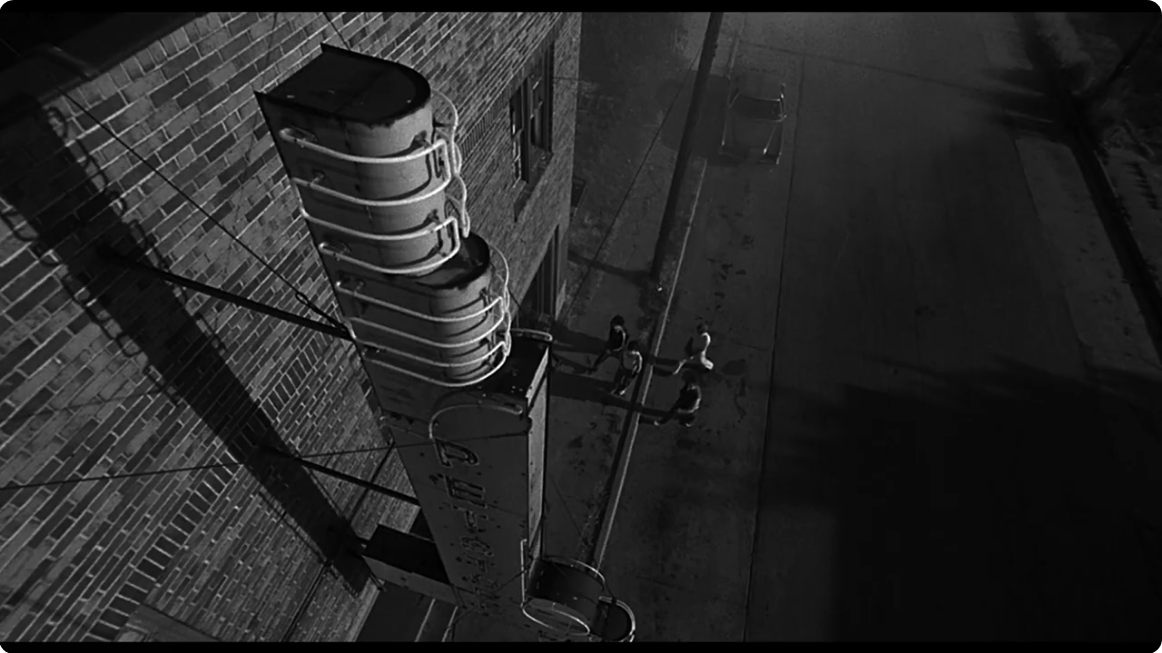

Danny Boy O'Connor reports on the discovery of a foundation stone from a demolished commercial building on Greenwood Avenue. The building, on the southeast corner of Greenwood and Latimer Street, was used by director Francis Ford Coppola as the pet shop in the movie Rumble Fish, based on the novel by Tulsa's S. E. Hinton. The stone will be moved to the Outsiders House for preservation:

You're looking at an 8-foot concrete footing, left buried on Greenwood from the original buildings featured in Francis Ford Coppola's Rumble Fish, based on S.E. Hinton's classic novel and filmed in Tulsa in 1982. I discovered this hidden piece of history a few years ago while searching for historic filming locations. I immediately thought the site would be a perfect location for a future museum. As fate would have it, I later met with Kimberly Johnson, CEO of the Tulsa City-County Library. To my surprise, this very site was the planned location for her new library in North Tulsa. I shared the story with her, explaining that a piece of cinematic history lay buried beneath the surface. I asked for permission to recover it for a future exhibit or museum, and she graciously agreed to let The Outsiders House Museum preserve it. Today was a good day! I can't thank Nathan Tuell and the team at Nabholz Construction enough for carefully digging out the footing and loading it onto our trailer. Huge thanks as well to Gary Coulson from The Outsiders DX in Sperry, Oklahoma, for helping transport and store it. And, of course, my deepest gratitude to Kimberly Johnson for making this dream a reality--allowing us to save the last remaining piece of the Rumble Fish pet store location. P.S. Thank you, Patrick McNicholas, for the reference photos and the photo mashes.

Rumble Fish and its locations inspired Chilean author Alberto Fuguet to visit Tulsa and then to create a documentary about the experience: Locaciones: Buscando a Rusty James (Locations: Looking for Rusty James"), which was screened at Tulsa's Circle Cinema in 2014.

The pet store location was a two-story retail building on the southeast corner of Latimer St and Greenwood Ave. The 1957 Polk City Directory says that Kyle's Sundry was at 1023 N. Greenwood, and the Kyle Apartments were upstairs at 1023½. This was one of the last surviving bits of a commercial area on the north end of Greenwood Avenue between King Street and Pine Street. Sometimes called Upper Greenwood, the area was considered more family-friendly than Deep Greenwood, at Archer. Many of the buildings, like this one, were two stories, with rooms to rent on the 2nd floor. There were a number of churches here, a movie theater (the Rex, just two blocks away at 1135 N. Greenwood), groceries, cafes, barber shops, and pool halls. The area was cleared as part of the City of Tulsa's urban renewal program. This sort of retail building, and the idea of having retail next to residential, was considered "obsolete" and "blight" by urban planners of the day, so it was demolished at some point in the mid-1980s.

Tulsa is the focus of another recent article from a UK newspaper website: A story in the Guardian Online about the impact of expressway construction on Tulsa's Greenwood neighborhood, and the possibility of reviving the neighborhood by removing the north leg of the Inner Dispersal Loop.

Twenty-five years before Don Shaw was born in Greenwood, a white mob invaded the Tulsa neighborhood and killed more than 300 people. Much of the tight-knit community was burned to the ground, including his grandfather's pharmacy.But when Shaw was growing up in the 1950s and 60s, few people wanted to talk about the massacre - perhaps in part because much of the damage was no longer visible.

He remembers walking the streets of Greenwood in his youth and seeing Black-owned businesses up and down its blocks: a hotel, dry cleaner, soul food restaurants, churches, a ballroom, dentists, pharmacies, hardware store, photo studio, the 750-seat Dreamland Theatre. It was an oasis of Black economic self-sufficiency, inside an Oklahoma city flush with oil industry wealth where the Klu [sic] Klux Klan once publicly operated.

"There was a lot of parties," recalled 76-year-old Shaw, who has lived in Greenwood his whole life. "Dances and stuff like that, concerts, lots of stuff going on."...

By December 1921, more than half of the homes that were destroyed had been rebuilt, despite city leaders rewriting zoning and fire codes to prevent the Black neighborhood from surviving. (Some Greenwood locals worked on their homes at night to avoid policemen.) When I-244 came decades later, resistance to the highway was undermined by a lack of Black representation in city government.

The Guardian story was apparently inspired in part by a graphic depiction of the effects of I-244 on the neighborhoods north, northeast, and northwest of downtown Tulsa, produced by New York City architect Adam Paul Susaneck for his @Segregation_by_Design Twitter account. Susaneck got in touch with me back in early June, looking for aerial photos and other information that would help him with a then-and-now visualization of the sort that he has done for many other cities, part of a long-term project (segregationbydesign.com) to depict vividly the destruction wrought by Federal highway and urban renewal funding.

Using historic aerial photography, this ongoing project aims to document the destruction of communities of color due to red-lining, "urban renewal," and freeway construction. Through a series of stark aerial before-and-after comparisons, figure-ground diagrams, and demographic data, this project will reveal the extent to which the American city was methodically hollowed out based on race. The project will cover the roughly 180 municipalities which received federal funding from the 1956 Federal Highway Act, which created the interstate highway system.Since the creation of the Interstate, freeway planning has been an integral tool in the systematic, government-led segregation of American cities. Used not only as a direct means to destroy the communities in their paths, freeways have also been used to cement racial segregation and ensure its endurance. Working synergistically with the legacy of redlining, freeway planning became the ultimate enforcement mechanism: literal walls of concrete and smog that separated black communities from white. In the name of the thinly veiled racist policies of "urban renewal," the freeways took the red lines off the map and built them in the physical world.

Here is the minute-and-a-half video on Tulsa, Greenwood, and I-244:

Greenwood, Tulsa--the famous "Black Wall Street"--before and after highway construction and "urban renewal."

— Segregation_by_Design (@SegByDesign) July 19, 2023

"Decades after the Tulsa Race Massacre [in 1921], urban 'renewal' [in the 1960s] sparked Black Wall Street's second destruction," writes @SmithsonianMag. pic.twitter.com/Qz099Ww1nt

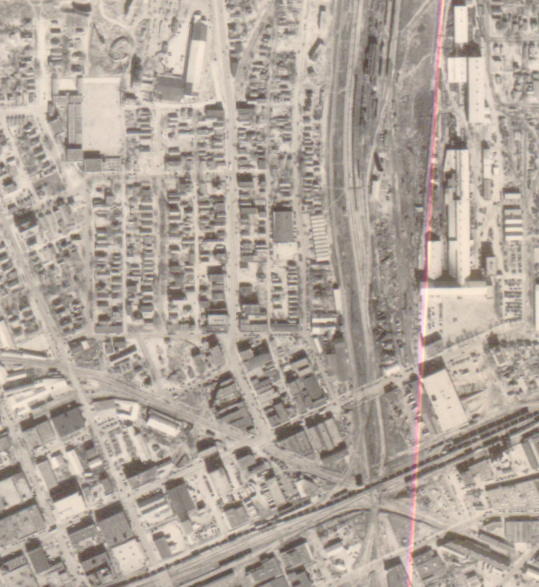

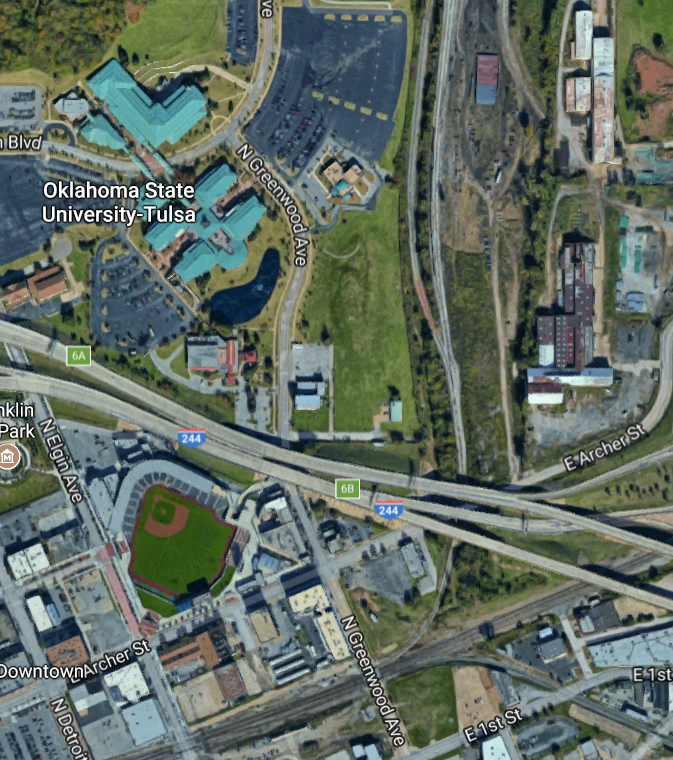

After a street scene from circa 1949, looking north on Greenwood from just north of Vernon AME Church, the video shows the same location today, with homes and shops replaced by today's empty OSU-Tulsa parking lots. The view shifts to a 1951 aerial, zooming in to Admiral Blvd and 1st Street, just west of Utica Ave. The view pans west, as a modern aerial photo replaces the 1951 aerial, showing not only the destruction in the immediate path of the expressway, but the erosion of neighborhoods bordering the expressway, with homes and churches and schools replaced by parking lots and industrial buildings.

At about 27 seconds in, we see an outline showing the boundary of the Greenwood District, and we see I-244 take out two-thirds of what had been a densely-developed business block between Greenwood, Hartford, Archer, and Cameron, and then another business block between Brady, Cameron, Greenwood, and Frankfort. Continuing west, the highway took out more homes and businesses in Greenwood and in the adjacent neighborhood west of Detroit Ave that I've called the Near Northside. A wider swath was cut to build the Cincinnati-Detroit interchange with I-244, and Cincinnati, which had stopped north of Standpipe Hill, now cut through it.

At 41 seconds, I-244 crosses Main Street, sparing Cain's Ballroom. A few seconds later, the massive northwest IDL interchange, connecting the Tisdale Expressway, the Keystone Expressway, and the west leg of the IDL (I-244) wipes out a working-class white neighborhood and cuts downtown off from Owen Park and Crosbie Heights. Edison Junior High gets cleared for the Keystone Expressway at 54 seconds, and then more destruction along the southern edge of the Owen Park neighborhood. When the expressway reaches Yukon Ave, the view zooms out to show a modern aerial view, with the expressways that ring downtown highlighted in yellow, and then the same view from 1951.

The devastation caused by the expressway was significant, particularly to the area known as Deep Greenwood, the commercial district centered on Archer and Greenwood. A May 4, 1967, Tulsa Tribune story, republished here on BatesLine, An Old Tulsa Street Is Slowly Dying, had a photo of the demolition of the Dreamland Theater (at the time, an Elks Lodge) and comments from merchants who were being displaced by the expressway.

The Guardian article discusses the $1.6 million FY22 Reconnecting Communities grant received by the North Peoria Church of Christ, for "I-244 Partial Removal Study." They hope to place the reclaimed land in a trust, to reconnect the street grid, and to avoid gentrification.

But the Grauniad story and the I-244 removal effort misses an important factor in the second demise of Greenwood. The damage done by the expressway was compounded by the "Model Cities" program, the new, Federally funded and allegedly humane approach to urban renewal. It, too, was adopted in 1967, the same year that the path of the expressway was cleared through the neighborhood. The aerial photo from September 10, 1967, suggests that had the expressway been the only insult suffered by the Greenwood District, it might have survived, but Model Cities cleared out everything except the churches and the little remnant of the commercial district south of I-244. Even the original Booker T. Washington High School building, which had survived the 1921 massacre (the L-shaped complex in the upper left of the photo below) was demolished in 1983 in the name of "renewal."

This past Saturday morning, after visiting the Greenwood Farmers and Artisans Market, I took some photos of the old Moton (Morton) Health Center complex just west of Rudisill Library, on the north side of Pine Street between Greenwood Avenue and Greenwood Place. According to the cornerstone, the original three-story, blond brick building dates to 1931 and was a municipal hospital. Charles Adrian Popkin was the architect; DeWitt and Howard were the contractors.

Sometime in the 1970s or 1980s (my guess, based on the style), an ugly extension was grafted on to the front of the building, and single-story outbuildings were constructed for additional clinic space. These outbuildings have signs labeling them as clinics for pediatrics, OB/GYN, nutrition, WIC, and dentistry. The roof of the historic building appears to be gone, at least partially. It appears to have been boarded up for at least a decade. Urban explorer David Linde has a photoset of the interior of Morton Health Center on Abandoned Oklahoma. The additions appear to have compromised the integrity of the historic building.

Tulsa Municipal Hospital (later known as Moton Memorial Hospital), 1931. The Beryl Ford Collection/Rotary Club of Tulsa, Tulsa City-County Library and Tulsa Historical Society. Accession # C1906.

Tulsa Municipal Hospital (later known as Moton Memorial Hospital), 1931. The Beryl Ford Collection/Rotary Club of Tulsa, Tulsa City-County Library and Tulsa Historical Society. Accession # C1906.The building was a hospital from 1932 to 1967, and was turned over by the city to a community board in 1941, when it was named Moton Memorial Hospital in honor of Robert Russa Moton, who had succeeded Booker T. Washington as president of the Tuskegee Institute.

In 1938, the Interracial Committee of the YWCA issued a "Study of the Conditions Among the Negro Population of Tulsa." The first page was devoted to medical care:

There is one hospital in North Tulsa located at 603 E. Pine St: Municipal Hospital.Equipment: 32 beds, but no beds for children. Condition of equipment: Inadequate.

Staff of hospital: 1 doctor, 4 nurses, 2 orderlies, 1 janitor, 1 cook. Nurses work an eight hour day and for $65 per month.

Charges to patients: None to charity cases. In ward: $17.50 per week. $20 per week for private room.

Hospital is maintained by the County. "A" rating in the small hospital class.

Other hospitals in Tulsa to which negroes are admitted:

Charges in above: Charity cases, none.

- St. John's Hospital at 21st and S. Utica: 13 beds

- Tulsa General at 744 W. 9th: 6 beds

$17.50 per week in ward and $25 per week in private room.

The report goes on to note that an outpatient and general clinic was "held daily, with no charge to the patient" at the hospital, "maintained by the County and is staffed by the regular staff of the hospital." The Public Health Association maintained weekly clinics for tuberculosis, child welfare, "immunizating," and prenatal care at 509 E. Archer Street, provided by a public health nurse and attending physician at no cost to the patient, maintained by Community Fund. For venereal diseases, the Public Health Association worked with patients at the Municipal Hospital. Crippled children were helped at a clinic at the YWCA at 621 E. Oklahoma Place, maintained by the Crippled Children's Society.

An item in the February 20, 1942, edition of the Tulsa Herald All-Church Press announced that the Women's Society (W.S.C.S.) of the First Methodist Church was donating 51 full-size sheets and three "draw sheets" to Moton Memorial Hospital, "Tulsa's hospital for negroes." That summer, incumbent Tulsa County District 3 Commissioner Ralsa F. Morley, running for re-election, wanted voters to know that he stood for the Tulsa County Clinic, Moton Hospital, and "All Out for Victory for America." In the spring of 1957, Moton, Hillcrest, and St. John's hospitals were to hold a week-long clinic to administer the first of three doses for the new Salk polio vaccine.

In 1967, Moton Memorial Hospital was closed and the facility reopened the following year as an ambulatory (outpatient) clinic.

A Model Cities (urban renewal) project report from January 1971 mentions a planned $2.25 million expansion that would "double the Clinic's Current capabilities." This is presumably the source of the ugly 1970s additions.

The Morton website says, "In 1983, and as required by BHC, the center was renamed. The name chosen was Morton Comprehensive Health Service in honor of W. A. Morton, M.D., a local physician with a distinguished record of service at Moton Memorial Hospital."

In 2006, Morton Comprehensive Health Services moved from this facility to a new building at 1334 N. Lansing, on the site of a neighborhood that was cleared by the Tulsa Development Authority to create an industrial park.

It would be lovely to see the ugly additions cleared away, the 1931 building restored, and the empty space around it filled with new development in a traditional urban style, with street-fronting retail and offices or apartments above.

In 2013, the city used brownfield remediation grants to remove asbestos and other hazards from the main hospital building. In 2017, a Houston developer named Michael Smith won TDA approval for Morton's Reserve, a project that would restore the 1931 building, construct a three-story mixed-use building around it, with a four-story apartment building to the north. Smith & Company Architects from Stafford, Texas, developed the site plan. But after a flurry of PR in 2017, nothing more seems to have happened.

In May 2021, Mayor G. T. Bynum IV announced that the old hospital will become an entrepreneurship incubator called Greenwood Entrepreneurship Incubator @ Moton (GEIM). No timetable is mentioned for restoring the building, but the post mentions the Morton's Reserve project, and in the meantime, a program called MORTAR Tulsa will provide mentorship and training for for-profit entrepreneurs.

MORE: On May 6, 1980, Cheri Poyas with the Junior League of Tulsa interviewed physician and surgeon Dr. Charles Bate, who came to Tulsa in 1940 and did much of his early work at Moton. He recalls that Moton had a rope elevator, no laboratory facilities, and a poor-quality X-ray machine. He recounts the special challenges of anesthesia, home births, treating tuberculosis, venereal disease, and small pox, and doing blood pressure screenings.

UPDATE 2021/09/06: A story in Tulsa People says that the redevelopment project will happen, but now the Moton building rehab will be funded and managed by Tulsa Economic Development Corporation, separate from the new development, which still involves Michael E. Smith, a Tulsa native now living in Houston.

"The hospital building sits on a 3.83-acre tract of land," he explains, "and I'm doing everything outside of the hospital building."This project will bring another level of single-family homes into the area -- 12-16 really nice East Coast-style, vertical three-story townhomes -- and then 64 units of multi-family," Smith continues. The whole complex, a $20 million project, will be called Morton's Reserve.

Both organizations plan to start project design later this year.

We shall see.

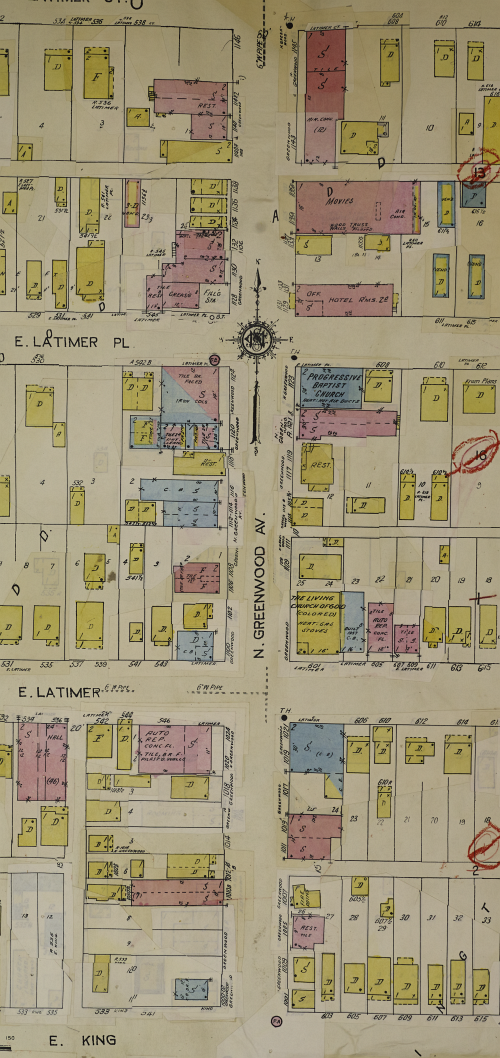

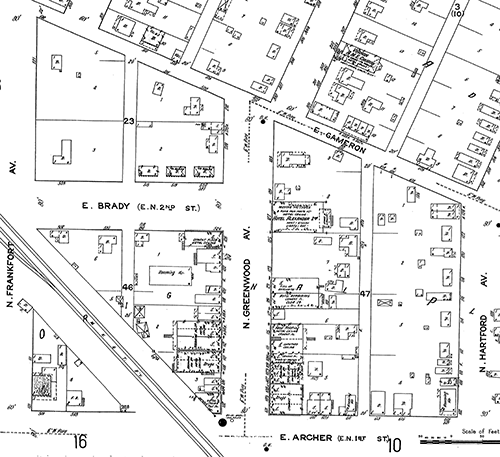

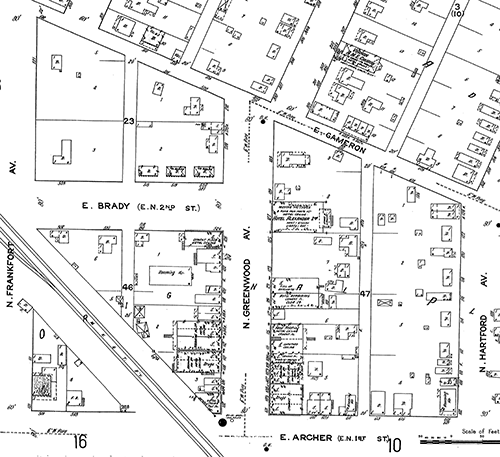

1915 Sanborn map showing the commercial section of Tulsa's Greenwood district a few years before its first destruction

1915 Sanborn map showing the commercial section of Tulsa's Greenwood district a few years before its first destructionTo journalists, photographers, and visitors, pilgrims this week of the centennial of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre: Welcome to Tulsa. Some context may help you interpret what you see and hear this week.

The cultural foundation for violent mob action on May 31 and June 1, 1921 was laid over the previous four years by Tulsa's respectable government, media, and business leaders, who openly encouraged mob violence against labor union organizers and other undesirables during the World War and afterwards. In the Tulsa Outrage, November 7, 1917, masked vigilantes whipped, tarred, and feathered 17 men connected with the International Workers of the World, an event that the front page of the Tulsa World cheered with the headline "Modern Ku Klux Klan Comes into Being." The Center for Public Secrets is featuring a series of articles by historian Randy Hopkins, "The Trail of Atrocity." There's an exhibit at the Center's space at 573 S. Peoria, Architects of the Massacre, open daily from 11 a.m. to 8 p.m. through Thursday, May 27, 2021. The exhibit illustrates the powerful Tulsans who set the tone for the 1921 pogrom and its roots in the extra-legal Councils of Defense established by Oklahoma governor Robert Lee Williams to suppress dissent after the U. S. entered World War I. Randy Hopkins spoke on this topic last night; tonight, Tuesday, May 25, from 6 p.m. to 8 p.m., Hopkins will speak again along with Chief Egunwale Asuman on "The Mask of Atonement: Tulsa's False Promise of Reparations."

Within a year of the 1921 massacre, Tulsa's African-American community rebuilt Greenwood, having first defeated in court an attempt by city officials to use zoning to block survivors from rebuilding on their own land, forcing the community further north. Survivors of the massacre called the rebuilt Greenwood greater than what had gone before. But Greenwood was destroyed a second time by city government, using federal highway and urban renewal money, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, driving an expressway through the district's very heart, and following up with the Model Cities urban renewal program that left only a single block of retail buildings and a handful of churches. City officials finally succeeded in driving Tulsa's African-Americans further away from downtown; displaced families were encouraged to relocate to cheaply built post-war subdivisions in far north Tulsa, neighborhoods that had been utterly white at the 1960 census.

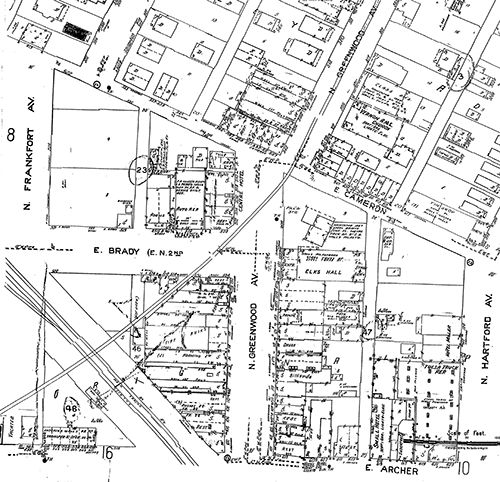

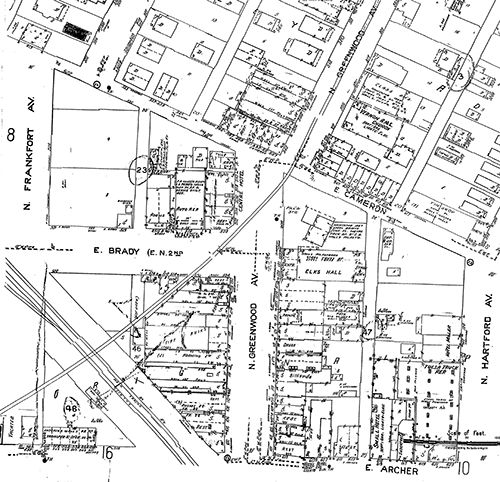

1939 Sanborn map showing the commercial section of Tulsa's Greenwood district, an area known as Deep Greenwood, after its rebuilding

1939 Sanborn map showing the commercial section of Tulsa's Greenwood district, an area known as Deep Greenwood, after its rebuilding

BatesLine has presented over a dozen stories on the history of Tulsa's Greenwood district, focusing on the overlooked history of the African-American city-within-a-city from its rebuilding following the 1921 massacre, the peak years of the '40s and '50s, and its second destruction by government through "urban renewal" and expressway construction. The linked article provides an overview, my 2009 Ignite Tulsa talk, and links to more detailed articles, photos, films, and resources, including the Solomon Sir Jones films, home movies that documented Greenwood and other black Oklahoma communities in the mid to late 1920s.

Carlos Moreno has written a series of feature stories, The Victory of Greenwood, on the men and women who built and rebuilt the community: John and Loula Williams, O. W. Gurley, A. J. Smitherman, Mabel Little, Ellis Walker Woods, to name a few. A book of the same title will be released on June 2.

You might notice that, up the hill and west of Martin Luther King, Junior, Boulevard (formerly Cincinnati Avenue), along John Hope Franklin Blvd (formerly Haskell Street) and nearby streets, there are empty blocks of land, with old brick foundations and concrete steps where homes used to be. These are not race massacre ruins. The homes you see, in a neighborhood that was untouched by the 1921 disaster, were acquired and cleared in the 1990s and 2000s by the city's urban renewal authority as part of the city's promise to provide 200 acres for a state university campus. About 80 acres of that land, now filled mainly with surface parking lots and a few academic buildings, came from the Greenwood urban renewal area; the rest came from west of MLKJr Blvd. I wrote a feature story, "Steps to Nowhere," for This Land Press, in 2014, about the history of this neighborhood, which was never part of Greenwood; that link will also lead you to photos and other articles about the neighborhood's history.

Photo copyright 2014, Michael D. Bates. 116 E. Fairview St., Tulsa. These are urban renewal ruins from the 1990s, not race massacre ruins from 1921.

Photo copyright 2014, Michael D. Bates. 116 E. Fairview St., Tulsa. These are urban renewal ruins from the 1990s, not race massacre ruins from 1921.The centennial commemorations have exposed divisions within Tulsa as a whole and even within the African-American community, with separate organizations sponsoring separate events.

The Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission is not an official body of state or local government, but it has become as unofficially official as possible, with elected officials appointed to its board, and the support of the City of Tulsa, the George Kaiser Family Foundation and other foundations, and the Tulsa Regional Chamber. This is the group sponsoring the new $20 million Greenwood Rising tourist attraction on the southeast corner of Greenwood and Archer; the group sponsoring the sold-out Remember and Rise event at the baseball stadium, headlined by Georgia politician Stacey Abrams and singer John Legend.

Many black Tulsans feel excluded and alienated by the Centennial Commission's plans. Former City Councilor Joe Williams seemed to speak for many people when he wrote:

This Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission and so-called remembrance of the destruction of Greenwood and slaughter of the several hundred innocent victims and celebration of Black Wall-Street is one entirely big joke. Most of US can't even get tickets to the main event including the Survivors and their Descendants because they were already saved up and reserved for the elite and other people from the outside. The power brokers and system are just trying to make it appear to the nation and world like we are all cumbaya and all good together here in T-town. They don't care at all about US or OUR community and the disrespect is intolerable. The day after May 31st our treatment will be back to the usual same-o-same-o status quo. They are pushing FAKE NEWS!

From a recent Human Rights Watch article on Tulsa:

Rather than working on such a plan [for reparations to survivors and descendants], city and state authorities have focused most of their efforts on creating the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission and its flagship project, the "Greenwood Rising" history center, which is meant to honor the victims and foster cultural tourism. The Centennial Commission has raised at least $30 million, $20 million of which went to build Greenwood Rising, but it has alienated massacre survivors and many descendants of victims by failing to adequately involve them in its planning....At least one survivor, 106-year-old Lennie Benningfield Randle, has issued a cease-and-desist letter ordering the commission to stop using her name or likeness to promote the project. All three living massacre survivors have sued the city of Tulsa, accusing it of continuing to enrich itself at the expense of the Black community by "appropriating" the massacre for tourism and economic opportunities that primarily benefit white-owned or controlled businesses and organizations....

The three living survivors of the massacre have said they do not plan to participate in any of the Centennial Commission's commemoration events. They will instead headline a community-sponsored event called the Black Wall Street Legacy Festival, which is the only centennial commemoration that includes and centers the survivors. They will be joined by US Senator Cory Booker, US Representative Sheila Jackson Lee, and the creators of the HBO hit series "Watchmen," which was situated in Tulsa and depicted the race massacre in its opening scene. Unlike the Centennial Commission's events, the Black Wall Street Legacy Festival will emphasize the Black Tulsa community's demand for reparations.

The three survivors, Lessie E. Benningfield Randle, Viola Fletcher, and Hughes Van Ellis, Sr., along with Vernon A. M. E. Church, and descendants of survivors who have passed on, have sued the City of Tulsa, Tulsa Regional Chamber, Tulsa Development Authority, Tulsa Metropolitan Area Planning Commission, Tulsa County Commission, the Sheriff of Tulsa County, and the Oklahoma Military Department in district court under public nuisance and unjust enrichment law. From the complaint:

The problem is not that the Defendants want to increase the attraction to Tulsa, it is that they are doing so on the backs of those they destroyed, without ensuring that the community and descendants of those subjected to the nuisance they created are significantly represented in the decision-making group and are direct beneficiaries of these efforts.

I note that page 47 of the complaint uses a graphic I created for my initial column on the "Greenwood Gap Theory" in the June 13, 2007, edition of Urban Tulsa Weekly. The graphic (shown earlier in this article) is a section of a 1951 aerial photo, overlaid with names of streets, landmarks, and railroads, along with the present-day path of I-244, a path that was cleared in 1967.

(Unfortunately, the complaint also misuses, on page 52, a graphic from my 2014 This Land Press story about the lost Near Northside, a photo of steps on the south side of Fairview Street between Boston and Cincinnati Avenues (now MLKJr Blvd), from which the BOK Tower in the background had been digitally erased. As detailed in the article, based on land records, street directories, fire maps, and aerial photographs, this neighborhood was a white neighborhood in 1921, was not damaged in the massacre, and survived until the City of Tulsa's urban renewal authority acquired the land in the 1990s.)

In addition to the Centennial Commission and the John Hope Franklin Center for Reconciliation is hosting its annual symposium May 26-29, with a keynote speech by Prof. Cornel West, and many other talks and panel discussions.

The Greenwood Cultural Center, located just north of I-244, is offering tours of the Mabel Little House (a house that was relocated from further north on Greenwood and rescued from urban removal), a special exhibit of the Kinsey African American Art & History Collection, a Sunday, May 30, "Brunch with the Stars," featuring Alfre Woodard, Tim Blake Nelson, Garth Brooks, Wes Studi, and Stanley Nelson, a June 2 panel discussion on the "Bitter Root" Comic Series, the Greenwood Film Festival, June 12 - 14, and a virtual reality film, The Greenwood Avenue Experience, June 15-17.

There is also conflict within the African-American community over the significance of the last remaining block of 1922 Greenwood that survived urban renewal. Small business owners there, mostly African-American, regard it as primarily a place of business, as it was before and after 1921. Other members of the community seem to see it primarily as a sacred space of remembrance. The Greenwood Chamber of Commerce, representing the building owners and businesses, publicly opposed the application by the Black Wall Street Legacy Festival to close Greenwood Avenue and were condemned by many for evicting a small business early this year for non-payment of rent. Business owners had mixed feelings about the Black Lives Matter mural that was painted on the street in front of their shops during the protests of last summer, with some feeling that it distracted from the story of 1921.

The Greenwood Chamber of Commerce is hosting its own event, the Greenwood Centennial Marketplace Showcase, May 28-30, which will include live music, food trucks, an art gallery, and a welcome center at 101 N. Greenwood, on the northeast corner of Greenwood and Archer.

The Black Wall Street Alliance is hosting the Faces of Greenwood Timeline Experience at the Black Wall Street Alliance Art Hall, 100 N. Greenwood (northwest corner of Greenwood and Archer), Saturdays and Sundays, 11 a.m. - 4 p.m., through July 17th.

The Black Panther Movement is sponsoring a National Black Power Convention, May 28-30, featuring a Second Amendment Armed Mass March for Self-Defense on Saturday, May 29, at 4 p.m.

Enjoy your visit. Mourn and celebrate. Learn the history in all of its complexity, a history that didn't stop in 1921.

Sincerely,

Michael Bates

P. S. Members of the community have expressed a desire to add their own messages to this open letter to visitors to Tulsa -- watch this space for those in the coming days.

Greenwood Ave., north of Easton St., looking north along Sand Springs Railroad interurban tracks toward intersection with Greenwood Pl. and the Del Rio Hotel, which was listed in the 1954-1956 editions of the Green Book.

Mike McUsic, a historical researcher on the topic of the Green Book, the segregation-era travel guide for African-American tourists, will be leading walking tours of the Green Book locations in Tulsa's Greenwood District on November 16 and 23 at 11:00 am. The tour is free (donation requested), with tickets available via Eventbrite.

Mr. McUsic has developed the Green Book Travelers HistoryPin site, locating 1,900 Green Book locations across the country, with names, descriptions, and historic and present-day photos. This link will take you to locations specific to Greenwood.

MORE: Here's a collection of links to BatesLine articles and other resources about Greenwood and Black Wall Street. Earlier this year, I wrote about the Green Book as additional evidence of Greenwood's post-1921 rebuilding and listed the Tulsa Green Book sites still standing.

Mike McUsic, a historical researcher on the topic of the Green Book, the segregation-era travel guide for African-American tourists, will be leading walking tours of the Green Book locations in Tulsa's Greenwood District on June 8th at 10:00 am and 3:00 pm, and on June 15th at 10:00 am. Tickets are $15, available via Eventbrite.

Mr. McUsic has developed the Green Book Travelers HistoryPin site, locating 1,900 Green Book locations across the country, with names, descriptions, and historic and present-day photos. This link will take you to locations specific to Greenwood.

Mr. McUsic provided a helpful correction to my piece about the fate of Tulsa's Green Book businesses with information about the address of Mince's Service Station -- Red's Bar at 325 E. 2nd Street, these days -- one of the handful of Green Book sites still standing.

MORE: Here's a collection of links to BatesLine articles and other resources about Greenwood and Black Wall Street.

A story published Monday by public radio station KGOU is another prime specimen of the cognitive dissonance that is the "Greenwood Gap Theory" -- the misconception that Tulsa's African-American neighborhood was never rebuilt after what is commonly known as the 1921 Race Riot (but more accurately described as a massacre).

"How Curious: Where Were Oklahoma's Green Book Listings" is the latest edition in KGOU's series of feature stories in response to listener questions. This year's winner of the Oscar best picture has called public attention to the annual series of guidebooks for African-American motorists, letting readers know where their business would be welcome in the days of Jim Crow segregation. According to the KGOU story, the Green Book was first published in 1936; the last edition was for 1966-67.

Oklahoma was first included in 1939. Remember that date. We'll come back to it.

The article paints a lively portrait of Oklahoma City's "Deep Deuce" district, where many of the businesses listed in the Green Book were located. N. E. 2nd Street was the commercial hub of the African-American community. There are a few pictures of businesses that are still standing today.

But what about Tulsa? Claire Donnelly writes:

In Oklahoma City and Tulsa, very few addresses listed in The Green Book are still standing.Many of Tulsa's listings were centered around the city's Greenwood District, which was looted and burned by white rioters in June 1921. According to the Tulsa Historical Society, 35 city blocks were destroyed and as many as 300 people may have died.

While those sentences are true, their juxtaposition suggests a causation that is impossible in the absence of time travel. The Green Book businesses, which were there in the 1930s, 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, are gone, not because of the riot, but because of urban renewal and expressway construction in the late 1960s: The "Model Cities" program, part of LBJ's "War on Poverty," and the construction of the north leg of the Inner Dispersal Loop, which cut through the heart of the Deep Greenwood commercial district.

Here's an excerpt from the 1939 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, showing Greenwood as it would have been the first year Oklahoma was mentioned in the Green Book.

I can't get too upset with Ms. Donnelly: She links to the New York Public Library's online collection of Green Book editions and to a spreadsheet collating all of the Oklahoma Green Book listings, which (I surmise) she assembled herself -- a very handy resource.

Based on the spreadsheet, these are the Tulsa Green Book listings still standing. Keep in mind that street numbers may shift over time; I'm going by the numbering on the Sanborn map. The spreadsheet has the year of each individual book in which the business appeared; I've summarized with a range.

- Cotton Blossom Beauty Parlor, 106 N. Greenwood, 1939-1941.

- Art's Chili Parlor, 110 N. Greenwood, 1950-1961. (The Bryant Building.)

- Mrs. W. H. Smith Tourist Home, 124 1/2 N. Greenwood, 1939-1962. (Now the second story above Fat Guy's Burger Bar.)

- Maharry Drugs, 101 N. Greenwood, 1939-1955. (Northeast corner of Greenwood and Archer.)

- Vaughn Drugstore, 301 E. 2nd St., 1939. (Now Yokozuna.)

- Mince Service Station, 2nd & Elgin, 1939-1954. (NW corner, 325 E. 2nd. Red's Bar, formerly Dirty's Tavern and Woody's Corner Bar.)

- Lincoln Lodge, 1407 1/2 E. 15th St., 1941. (Aquarian Age Massage.)

The latter three are surprising, because they are outside the Greenwood District, in areas that might have been considered off-limits to African Americans. Association with the Green Book should add to the historic importance of these buildings.

Another location of note is the Avalon Motel at 2411 E. Apache St., on the northeast corner of Apache and Lewis, listed from 1954 to 1962. Before completion of the Gilcrease Expressway, this stretch of Apache was part of State Highway 11, which began at 51st and Memorial, headed north to Apache at the edge of the airport, then west to Peoria, and north to Turley, Sperry, and Skiatook. The motel, a simple one-story, park-at-your-door accommodation, was still there within my memory, but the site has been vacant for at least a decade. While many motels were built along US 66 around the same time, this appears to be the only motel catering to black tourists.

A concluding thought on the Greenwood Gap Theory: While it's easy to jump to the conclusion that Greenwood was never rebuilt after 1921 -- in the absence of city directories, aerial photography, Sanborn maps, and now the Green Book -- I suspect that the misconception has persisted in part because the civic leaders who were responsible for the second destruction of Greenwood in the 1960s and 1970s were still active in the community until not that many years ago and would have been quite happy to avoid any public blame for their decisions. Easier to remain quiet and let the folks sitting across the foundation boardroom table blame 1921 racists for the demolitions you promoted and approved.

MORE: You can find my omnibus overview of Greenwood's history, with links to further articles, images, and films, here.

UPDATED 2019/05/06, with a correction from Mike McUsic regarding Mince's Service Station. He provided a photo of a 1942 telephone directory listing Mince's at 325 E 2nd Street. McUsic will be leading walking tours of the Green Book locations in the Greenwood District on June 8th at 10:00 am and 3:00 pm, and on June 15th at 10:00 am. Tickets are $15, available via Eventbrite. McUsic has developed the Green Book Travelers HistoryPin site, locating 1,900 Green Book locations across the country, with names, descriptions, and historic and present-day photos. This link will take you to locations specific to Greenwood.

Tulsa's Near Northside neighborhood, whose rise and demise I documented in a 2014 story for This Land Press ("Steps to Nowhere"), is part of an area that will be the subject of the Unity Heritage Neighborhoods Design Workshop, next week, September 11-15, 2017, led by urban design students from Notre Dame:

The University of Notre Dame Graduate Urban Design Studio will be traveling to Tulsa to work with our community to provide positive visions for future development. The studio will be conducting a 3-month design study focused on the Unity Heritage Neighborhoods located immediately north of downtown. The study broadly encompasses areas such as the Brady Heights Historic District, Emerson Elementary, Greenwood, and the Evans-Fintube site. To kick-off this effort, the studio will be conducting a week-long design workshop from September 11th - 15th to meet with the local community, to hear our thoughts for the area, and to begin envisioning the possibilities with us through a series of visual urban and architectural designs. Come on out and imagine the future together!

The workshop includes three events for public input and feedback. All are free and open to the public, but RSVPs would be appreciated. The links below will take you to the registration page for each event.

Workshop Introduction & Initial Community Input: Monday, September 11th, 2017, 6-8pm, at 36 Degrees North, 36 E. Cameron St. (That's just east of Main on Cameron in the Brady Bob Wills Arts District.)

Meet the team. Hear about the components necessary for making vibrant, walkable, mixed-use, diverse, and inclusive cities, towns, and neighborhoods. Share your vision and desires for the area.

Mid-Week Design Presentation & Initial Feedback: Wednesday, September 13th, 2017, 6-8pm, at the Greenwood Cultural Center:

Check out the in-process urban and architectural designs and provide feedback for the students to work on to further shape the vision.

End-of-Workshop Design Presentation & Feedback: Friday, September 15th, 6-8pm, at Central Library:

See the final designs from the week and provide your thoughts and feedback for the students to continue to work on during the remainder of their study. The studio will return to Tulsa in December to present their final designs and findings for the community to use as an ongoing resource.

MORE: Here's my Flickr set of images of Tulsa's lost Near Northside.

Relevant to yesterday's post on the Smithsonian Channel documentary that misrepresented the history of Greenwood, Tulsa's historic African-American neighborhood that its residents rebuilt after it was sacked and burned in the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot. The rebuilt neighborhood thrived and prospered for decades, becoming known as Black Wall Street, before urban renewal and expressway construction destroyed it again in the late 1960s. Here is a news story from the time that illustrates the social and financial impact of the decision to route the expressway through the heart of the Deep Greenwood commercial district.

From the Tulsa Library's online "vertical files," this article from the May 4, 1967, Tulsa Tribune, shows a photo of the demolition of the Dreamland Theater to make way for I-244. The story reports on the number of long-time small businesses that are closing down because they can't get financing to reopen somewhere new. Although the library's PDF has OCR text, it is full of mis-scanned words, so I decided to transcribe it here, and correlate it with other contemporaneous sources of information.

An Old Tulsa Street Is Slowly Dying

Greenwood Fades Away Before Advance of ExpresswayBy JOE LOONEY

An old man walked doen the sunny side of Greenwood Avenue and paused to stare at a pile of rubble.

Across the street, Ed Goodwin looked out the window of the offices of the Oklahoma Eagle and shook his head. "That's L. H. Williams," the Negro publisher said. "He comes down here every day. Since he had to sell out, he's just put the money in the savings and loan and lives off the interest . . ."

Ed Goodwin and L. H. Williams grew up with Greenwood Avenue. They remember the early days, when the first buildings were put up in the two blocks north of Archer Street.

They saw the riot of 1921, when many of the buildings burned. They saw the street rebuilt, grow and prosper. They saw, too, as a slum festered.

And now they are watching Greenwood Avenue die.

Its business district will be no more.

THE CROSSTOWN Expressway slices across the 100 block of North Greenwood Avenue, across those very buildings that Goodwin describes as "once a Mecca for the Negro businessman--a showplace."

There still will be a Greenwood Avenue, but it will be a lonely, forgotten lane ducking under the shadows of a big overpass. The Oklahoma Eagle still will be there, but every forecast is that some urban renewal project will push down the buildings that have not already been torn down by the wrecking crews clearing right-of-way for the superhighway.

Williams' son went to college and got a degree in pharmacy. He helped his father in the drug store, later was its manager. Today, he is looking for a job. He can't get financing to build another drug store anywhere.

"Very few of the businessmen here are able to get the financing they need to relocate," Goodwin said. "A Negro just can't do it. So, most of them are just out of business."

IT WAS BECAUSE of financing that Goodwin stayed on the street when [sic] he grew up instead of building a new office in another neighborhood.

His father operated a grocery store in a building across the street--one of those torn down to make room for the expressway.

"He built it in 1915," Goodwin recalled. "and it was destroyed in the 1921 riot. But he rebuilt and there was a grocery store there until 1930. I ran a furniture store there for a while, then put the Eagle office in there in 1936."

There, the Oklahoma Eagle remained until last year.

Goodwin owned an old theater building. It was not in the path of the highway.

"I wanted to put the paper out closer to my house, but they wanted so much money for the property, I decided it would be better to put the money into the building."

In the midst of old buildings, most of them dark, red brick structures dating to the early 1920s, he built a shining modern buff-brick structure. Behind the new building housing the Eagle, in what had been the orchestra pit of the old theater, he put a sunken garden.

OTHER PIECES of history have scattered away. There was the Dreamland Theater. J. W. Williams built it in 1916, then rebuilt it after it burned in the 1921 riot. A Negro Elks lodge moved in years ago, and this was a leading social center for the Negro community.

A rather substantial expressway pillar is slated to plunk down just about where the lobby of the theater was. The Elks managed to find a house 15 blocks up the street and there they moved a few weeks ago.

Otis Isaacs had a shoe shop next door. He rented his space from Alex Spann, who owned many of the buildings on the street. lsaacs had to shift for himself. He found a place 10 blocks away.

Attorney Amos Hall had an office downstairs. and upstairs had provided space for the Negro Masonic Lodge, of which he is Grand Master. Hall and his lodge both moved Into a building five blocks away.

BUT THE WILLLIAMS Drug is not being relocated. Nor has barber Joe Bulloch found a new place to go into business. Dr. A. G. Bacholtz has given up the private practice he carried on for so long on Greenwood Avenue, and is working with the City-County Health Department.

And Alex Spann. the building owner. He had a pool hall. With the money he got for his buildings, he bought another old pool hall a mile up Greenwood.

Hotel owner A. G. Small couldn't build another hotel anywhere. So he decided to retire. Mrs. Joseph W. Miller, whose late husband built a hotel which she operated, also could not rebuild. She, too, has retired.

A couple who operated a cafe gave up their own business and went to work for restaurants in downtown Tulsa. A man who owned a garage was just about able to get his mortgage paid off from the funds from the sale of the building to the highway department. He is not back in business anywhere else.

PAT WHITE was able to move his barbecue stand into a new home on Pine Street. The Christ Temple CME Church moved to Apache and Lewis.

"There is no Negro business district anymore," Goodwin said. Tulsa attached the name of Greenwood to the entire district occupied by Negroes--a name that ironically came from the city of Greenwood, Miss., a pIace hardly considered a Mecca for Negroes.

"They might as well take down all these parking meters," the publisher said. "There's nothing to park here for anymore."

In its heyday, it was a busy street. But the buildings grew old. The Negro population moved into newer neighborhoods. Slowly, integration opened a few doors downtown, on the other side of Archer Street. Places to eat. Go to a movie. To work at good jobs.

RAUCOUS CLUBS and rooming houses sprang up around Greenwood and Archer. Long before the expressway came and brushed the old street away, it was a dying street, like the main street of many an old, small town.

The future? A question mark for some like L. H. Williams Jr. More certain for young Jim Goodwin, who like his father became a lawyer, or for Ed Goodwin Jr., who edits the newspaper his father publishes. For others, they simply are passing from the scene, like the street they knew for half a century.

Right-of-Way for Crosstown ExpresswaySOMETIME, POSSIBLY about four years from now, an elevated eight-lane expressway will cross Greenwood Avenue between Brady and Cameron Streets.

Right-of-way for the project is now being cleared. This Tribune photo looks northwest along the construction path.

Greenwood enters the picture at the upper left, and the buildings in the right background are on Cameron.

The expressway will be about 30 feet above the ground as it crosses Greenwood.

It will carry the designation Interstate 244, and will be part of the Crosstown Expressway which forms the north side of a planned inner dispersal loop around the downtown area.

East of Greenwood, the project is taking nearly all the land between Cameron and Archer Streets as far east as the Texas & Pacific Railway (formerly the Midland valley) tracks.

The expressway will cross Archer Street and both the T&P and Santa Fe railroads east of Hartford Avenue.

West of Greenwood. the right-of-way runs northwesteriy, crossing Cameron before it gets to Frankfort Place.

Here is a section of the January 5, 1951, aerial photo showing Deep Greenwood.

Here is the same area, from the September 10, 1967, USGS aerial photo, taken just four months after the Tribune article. As you can see, the expressway cuts right through the heart of the Black Wall Street business district. Had planners moved the expressway a block further south or perhaps built over the broad Frisco right-of-way, Greenwood would not have lost its commercial heart. Who decided the exact route is a question worth investigating.

Here is the same area as it is today, from Google Maps.

The buff-brick building mentioned in the story is still the home of the Oklahoma Eagle, at 624 E. Archer St., the SW corner of Archer and Hartford. The mention of the theater and orchestra pit on that property sent me looking: Sanborn's 1915 map shows a single-story building labeled "moving pictures" on the south side of Archer just east of the north-south alleyway that split the block; that's west of the "new" Eagle building. 1939 and 1962 maps show a two-story building, about twice as deep as the theater, with rooms on the 2nd floor and two retail spaces on the first floor.

Here is the 1962 Sanborn map covering most of the area described in the article:

On the jump page are lists of businesses, from the 1957 Polk City Directory, on blocks that were affected by demolition. To add context, I've included buildings that were spared (at least spared by the expressway, but those buildings that were demolished for the expressway are shown in bold; italics indicates a business mentioned in the Tribune story. Even though this directory was published a decade before demolition, it's notable that so many businesses were still around 10 years later, persisting until the end. It's also notable that there were so many small, family-owned businesses and so many residences in such a concentrated area.

There was some excitement among Tulsa history buffs when it was learned that the Smithsonian Channel would be showing colorized clips from home movies showing Greenwood, Tulsa's historic African-American district, as it was in the mid-to-late1920s. Instead we have another instance of the erroneous notion I call the "Greenwood Gap Theory" -- the idea that Greenwood was never rebuilt after the riot -- this time being promulgated by one of America's most respected cultural institutions.

The Smithsonian Channel is not available on cable TV in Tulsa, but the program, "America in Color: The 1920s," is available to watch on the Smithsonian Channel website, free of charge. The segment on Greenwood begins about 16 minutes into the program and lasts about 90 seconds.

As American Heritage reported back in September 2006 (noted here on BatesLine a few days later), Oklahoma historian Currie Ballard had acquired 29 cans of film that had been taken by Solomon Sir Jones, a black Baptist preacher, who had been assigned by the National Baptist Convention "to document the glories of Oklahoma's black towns." Yale University has made the Solomon Sir Jones film collection available for viewing online. The stills above are from Film 18; the stills below, from the offices of the Oklahoma Eagle in 1927, are from Film 2.

It's disappointing that Arrow International Media (producers of this Smithsonian series) chose to present images of a prosperous Greenwood (and Muskogee) circa 1925, followed by film of the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot. The order of presentation and the narration leave the viewer with the impression that the riot destroyed the prosperity shown in the Jones films when in fact, the Jones films depict the triumphant resurgence of the Greenwood community after the riot.

It's understandable that a member of the general public, knowing about the 1921 Riot and seeing the area as it is today, might leap to the conclusion that Greenwood was never rebuilt. But the producers of the Smithsonian video had access to all the information they needed to tell the complete story.

Doug Miller of Müllerhaus Legacy, a publishing house in Tulsa, debunks the Smithsonian presentation with precision and passion.

I was initially excited today to see that the Smithsonian Channel was including Greenwood in a new documentary entitled "America in Color." But, upon watching the section that discussed Greenwood and the race riot, I was saddened to see an almost total misrepresentation of the the film footage. I immediately saw significant errors and omissions that, in my opinion, rob Greenwood of its rightful legacy.As you'll read below, the mistakes are many and were so obvious that I can only assume they were made knowingly with the intention of elevating narrative above fact. It's a practice that has become common place in the news media today. Sadly, it has apparently also filtered down to historians. Before supposing that these errors don't really matter, I hope you'll read my entire post. I outline the errors that I think matter very much. And I explain why.

Miller lists and rebuts five egregious errors in the segment: (1) None of the footage shows Greenwood before the riot, as the narration implies. (2) Much of the street footage shown was actually from Muskogee, as Rev. Jones's meticulous title cards clearly indicate. (3) Greenwood's founding is misrepresented. (4) The riot is depicted as an attack motivated by universal white resentment against Greenwood's prosperity; the reality, documented in contemporary news sources, is much more complex.

The fifth error does the greatest cultural damage:

Fifth, and most damning: the film says nothing of Greenwood's rightful legacy. Perhaps I should not single out this film on this point. Most tellings of the Tulsa Race Riot are, in my opinion, guilty of doing the same. I have long been of the opinion that the rebuilding of Greenwood needs to take its rightful place as one of the single most powerful and inspirational stories of Black America's fight to overcome the injustice of segregation and racial inequity. When one fairly considers the breathtaking scope of the destruction, the speed of reconstruction, the opposition to rebuilding (even within the black community), and the defiant independence with which the community achieved all they did, one cannot help but be moved at the level of the soul.Yet, while the story of the riot is advertised far and wide, very few Tulsans and even fewer outsiders know the glorious story of Greenwood's rebuilding. From my own personal interactions, I dare say that most Tulsans believe that Greenwood's history ended in 1921. Many people are shocked to find out that Greenwood reached its economic peak in 1941 and continued to thrive well into the 1960s.

No, the white mob did not win. Greenwood won. And that should be what every Tulsan remembers best about the legacy of Greenwood. It is a story of remarkable victory, not defeat and destruction. To say otherwise is to deny the inconceivable achievement of every African American father and business leader who died protecting their community and their families during that horrific event. And, who chose to defiantly stay in Tulsa to rebuild.

Miller is absolutely right on all points: Most people assume that the Riot is the reason that so little of Greenwood remains (and that the neighborood to the west is vacant except for a few eerie Steps to Nowhere).

Miller is right, too, that the rebuilding of Greenwood is an inspirational story of African-American resiliance, perserverance, and initiative in the face of violent racism that every Tulsan, every American ought to know.

So why is there this preference for the Greenwood Gap theory, the notion that "Greenwood's history ended in 1921"? Why is the rebuilding rarely mentioned in discussions of the Riot?

I have two hypotheses: One speaks to local political concerns and the other deals with national cultural sensitivies.

The local hypothesis is that Tulsa's civic and cultural leaders found it more pleasant to leave people with the incorrect impression that Greenwood was never rebuilt than to face their own culpability in its second destruction. If you remind people that Greenwood was rebuilt, bigger and better than before, according to eyewitness accounts, it raises a question in their minds: Why isn't it here anymore? And the answer to that question raises questions about decisions made, mainly in the late 1960s, by people who were still alive and active in city government and community affairs for decades afterward:

- Who signed off on the decision to run I-244 right through the heart of Deep Greenwood?

- Who decided that the Greenwood and Lansing Avenue commercial districts should be demolished?

- Who decided to demolish the original Booker T. Washington High School, a building that had survived the 1921 Riot?

- Why were the promises of new and better housing, retail, and community facilities never fulfilled?

- Who among African-American community leaders lent their support to these plans?

- How is it that a well-intentioned, progressive program like Model Cities, part of President Johnson's War on Poverty, resulted in the destruction of Black Wall Street?

It's easy to imagine city leaders thinking: Better that Tulsans should blame long-dead city leaders and anonymous rioters for the destruction of Greenwood than to wonder about the judgment of present-day leaders who signed off on its second destruction.

Some day, someone needs to write the history of urban renewal in Tulsa, with a particular focus on the Greenwood District and Model Cities.

But these local factors would not have influenced the writers and producers of the Smithsonian documentary.

This is the most generous spin I can put on it: They couldn't believe that Greenwood was rebuilt so quickly after the riot (or at all), so they assumed that the dates on the films were incorrect and that the scenes of prosperity predated 1921.

My hypothesis regarding Greenwood and national cultural sensitivites is twofold: First, that the story of Greenwood's reconstruction would undermine the left-wing narrative that only government action can right societal wrongs, which are the result of capitalism and individual liberty. This was the gist of OSU-Tulsa Professor J. S. Maloy's objection to my 2007 column about the Greenwood Gap theory, expressed in a letter to Urban Tulsa Weekly: "The free market will always indulge racism, ignorance, fear, and sheer pettiness of spirit in the name of profits. Only a democratic process--public investment constrained by public consultation--can do better." While his letter to UTW is not online, the original version of my rebuttal is here, detailing my sources and inviting him to do his own investigation. Maloy's apparent ideological commitment to the superiority of government action to voluntary action led him to disbelieve documentary evidence to the contrary.

Second, that the reconstruction of Greenwood and the resilience of its people raises uncomfortable questions about present-day American culture. If Tulsa's African-American community could rebuild within a year, despite government-imposed obstacles, despite the resurgent Ku Klux Klan, what was it about the character and social capital of that community that we lack today?

TAKE ACTION: Tulsans concerned about an accurate portrayal of Greenwood's resurgence can contact the Smithsonian Channel and urge them to issue a correction and to edit the narration and sequence to reflect the correct locations and chronology.

We would love to hear your thoughts. Send Smithsonian Channel your suggestions, comments, questions, and concerns to contact@smithsoniannetworks.com or call us at 844-SMITHTV (764-8488).

It is an exciting thing to see Greenwood alive as it was in its heyday.

The Solomon Sir Jones collection of films, discovered about seven years ago by Oklahoma historian Currie Ballard, is available for viewing on the website of Yale University's Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. In 2006, Ballard was concerned about finding a home for these rare and precious films documenting the resilience and industry of African-Americans in Oklahoma. Within three years, the films were available through Global Image Works. Now Yale is making them available for viewing and download.

Dr. S. S. Jones was a Baptist pastor in Okmulgee, a denominational leader, and a businessman. This collection consists of about six hours worth of film, in 29 reels, of African-Americans in Oklahoma in the mid-1920s. Jones had a good 16 mm camera and a kit for making titles using white letters on a black background; nearly every segment has an identifying title.

Jones would occasionally insert other films or shots of photographs. Film 18 begins with a short, stock clip of Pacific coast fishermen. That was followed by a procession of 71 white-robed baptismal candidates and hundreds of other church goers entering First Church in Okmulgee. I could imagine Jones showing this silent film to a group and narrating something about being fishers of men.

Starting about 5 minutes in, there are extended clips of Tulsa's Greenwood District: The S. D. Hooker Dry Goods company at 123 N. Greenwood; smartly-dressed members of the Tulsa Business League; photos of Mt. Zion Baptist Church, destroyed just two months after it was dedicated, and then film of the church as it was at the time -- just the basement that survived the riot; the C. B. Bottling Works at 528 E. Archer (SW of Archer and Greenwood); street scenes on Greenwood, including a funeral procession of cars; students at the noon hour at Booker T. Washington High School and on the playground and in the agricultural gardens at Dunbar Elementary School.

On film 28 there is about three minutes footage of C. C. Pyle's Bunion Derby, including close-ups of winner Andy Payne and many of the other runners.

Of course, this isn't just about Tulsa. Okmulgee, Muskogee, Taft, Boley, Okay, Langston, Porter, Coweta, Hugo, Bristow, Wetumka are among the other Oklahoma cities and towns featured in these movies.

This is really exciting stuff.

UPDATE 2024/09/30: The Yale caption at the end of Film 2 identifies a civic auditorium as Tulsa's, but the fenestration and relationship to the street don't match Tulsa Municipal Theater. It does match the Birmingham, Alabama, Municipal Auditorium, now known as Boutwell Memorial Auditorium. The building, opened in 1924, still stands, but with a modern entry hall that was constructed in 1957 on the plaza in front of the auditorium shown in the 1927 film.

The National Baptist Sunday School and Baptist Young Peoples Union Congress was held at Birmingham's Municipal Auditorium June 8-13, 1927. Here are three newspaper clippings, the first announcing the meeting, the second welcoming delegates, the third reporting the close of the convention, featuring a speech by Dr. S. S. Jones and a parade through the city, led by a brass band and "Sunday school boys wearing the khaki," which are seen in the film. The June 11 edition also has several display ads from various businesses welcoming delegates. The biennial congress of the Southeastern Federation of Colored Women's Clubs was held in Birmingham the same week.

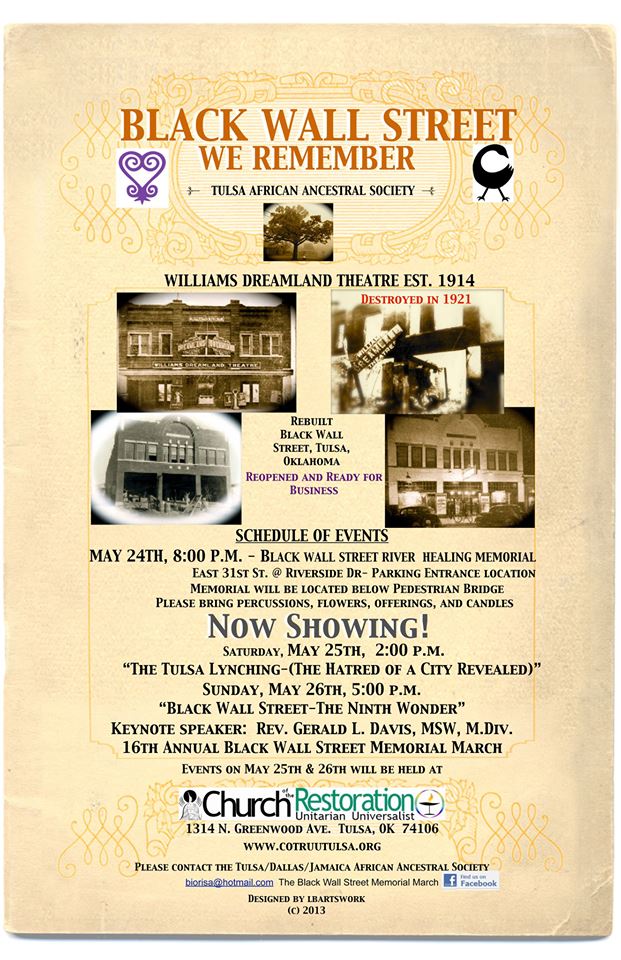

This looks interesting. Tonight, Sunday, May 26, 2013, at 5 p.m. at the Church of the Restoration, 1314 N. Greenwood Ave., there will be an event sponsored by the Tulsa African Ancestral Society, entitled "Black Wall Street: The Ninth Wonder." The poster shows four photos of the Williams Dreamland Theater: Before the 1921 Tulsa race riot, the gutted theater in the aftermath of the riot, the new theater under construction, and the new theater open for business. The photos and the caption -- "Rebuilt Black Wall Street, Tulsa, Oklahoma, Reopened and Ready for Business" -- suggest that the event will be about the post-riot resurrection of Tulsa's African-American neighborhood. I've written about the rebuilding of Tulsa's Greenwood District and its ultimate dismantling by expressway construction of urban renewal; perhaps this event will have the same theme.

One of the fun things about blogging for over eight years is when someone posts a comment or sends an email about a long-ago blog entry. Someone is searching on the web for information, perhaps about family or friends, and finds one of my entries, then writes a note to fill in more details, often with a touching personal story.

One of the fun things about blogging for over eight years is when someone posts a comment or sends an email about a long-ago blog entry. Someone is searching on the web for information, perhaps about family or friends, and finds one of my entries, then writes a note to fill in more details, often with a touching personal story.

Yesterday, Brenda Terry posted a comment on my entry on the 90th anniversary of the Tulsa Race Riot, in which I talked about Greenwood after the riot -- its rebuilding and flourishing, followed by its second demolition in the name of urban renewal. She offered her own recollections and those of her mother. Brenda is the daughter of blues great Flash Terry; Rocky Frisco recalls sitting in with Flash's band on Greenwood back in 1957, one of the anecdotes I cited in my talk about Greenwood's post-riot rebirth.

Thanks Mike for the information posted on this site regarding Greenwood's Post Riot history.I am actually the oldest daughter of Flash Terry, you mentioned him briefly in your presentation. Recently my mother spoke about musicians who visited our house in the late 1950's before they were famous (i.e. Curtis Mayfield, Bobby Blues Bland, but that's another story).

My mother grew up on North Owasso, west of Peoria during the late 40's after her mother died. Her mother, before she died in 1940, lived directly across the street from the Mt. Rose Baptist Church on Lansing. She speaks fondly of those days, and of Greenwood. Actually everyone you speak with about Greenwood who is old enough to remember the 20's, 30's, 40's, 50's and 60's in those days, speak with a hint of pride in their eyes, and a longing for the unity and pride they experience is visible in their voices. One of the memories I have as a very small child in the late 50's, is of my aunt who lived in one of the rooming houses on Deep Greenwood (looks like one of the homes in the photos posted). She worked as a dispatcher for a taxi company. Even now I can remember how bustling and alive the area was back then. When I think of the history plowed down in the name of progress, my heart sinks. The neighborhoods were a testimony for strong and determined people, who in some cases, had fought their way up from the bonds of slavery. During Urban Renewal development, my great-grandmother's home (where I was born),and rental property were destroyed.

Years later, Dunbar Elementary School where both my mother and her children attended, destroyed. I am ashamed that every residence who had history in not only Greenwood, but North Lansing, Owasso, and other streets now under I75, did not make their voices heard, and more importantly make themselves understood. I was a teenager at the time with no interest in history, but since I began researching my family history, I have learned that to know our history is to understand ourselves. Without this knowledge we have no foundation and lack direction.

Thanks again and with deep regards, Brenda.

I'd like to give the cover story in the new issue of This Land the attention it deserves, but at the moment I'm overwhelmed by a backlog of entries in progress about the Tulsa City Council primary, now just eight days away, so we'll make do for now with links:

Lee Roy Chapman has written a detailed, well-researched historical essay on the links between Tulsa founding father Tate Brady, the Ku Klux Klan, a vigilante attack on IWW members (and the daily newspaper that supported it), and the city's attempt to dispossess the black Tulsans whose homes and businesses had been burned and looted in the attack on Greenwood (the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot).

Sidebars to the story: Steve Gerkin's history of Beno Hall, Tulsa's Klan HQ on north Main St., and a transcript and audio re-enactment of Tate Brady's testimony to the tribunal investigating Klan activity in Tulsa.

Fox 23 spoke to Tulsans about changing place names that honor Brady, including the Brady Heights historic neighborhood, Brady Street, and the Brady Arts District. I'm inclined to agree with 94-year-old race riot survivor Wess Young:

He doesn't want the neighborhood's name to change. "That's history, why would you try and change what has gone one and not show what progress you have made," he told FOX23. He says he doesn't live in Tate Brady's neighborhood, he lives in his neighborhood. No matter what name it has. "It doesn't bother me because I have the privilege to live where I can afford."

My thinking -- keep Brady Street and Brady Heights as a humbling reminder that men like Brady were a part of Tulsa's past, but pick a better name to market the area north of the tracks downtown. I like Lee Roy Chapman's suggestion: Call it the Bob Wills District.

On the night of May 31, 1921, a white mob descended upon Tulsa's African-American district, known as Greenwood after its principal avenue, looting, shooting, and firebombing into the following day. The attack killed hundreds and left thousands wounded and homeless and destroyed dozens of African-American businesses and churches.

Once hushed up, the attack known as the Tulsa Race Riot has received an increasing amount of public attention in recent decades. I have half a shelf taken up with books on the topic, and I will leave that history to others who have told it far better than I could ever hope to do.

What is often overlooked is the triumph and tragedy that followed the riot. The story of Tulsa's Greenwood District did not end in 1921, and over the last few years I've taken it upon myself to learn that story and attempt to bring it to a broader audience.

After the riot, there was an attempt by the city's white leaders to keep Greenwood from being rebuilt. The City Commission passed an ordinance extending the fire limits to include Greenwood, prohibiting frame houses from being rebuilt. The idea was to designate the district for industrial use and resettle blacks to a new place further away from downtown, outside the city limits.African-American attorneys won an injunction against the new fire ordinance; the court decreed that it constituted a violation of the Fourth Amendment, a taking of property without due process. The injunction opened the door for Greenwood residents to rebuild.

They did it themselves, without insurance funds (most policies had a riot exclusion) or any other significant outside aid....

The Greenwood district flourished well into the 1950s. In 1938, businessmen formed the Greenwood Chamber of Commerce. A 1942 directory lists 242 businesses, including over 50 eateries, 38 grocers, a half dozen clothing stores, plus florists, physicians, attorneys, furriers, bakeries, theaters, and jewelers -- more than before the riot 21 years earlier. The 1957 city directory reveals a similar level of commercial activity in Greenwood....

The rebuilding, subsequent renaissance, and final removal of Greenwood are documented by aerial and street photos, land records, fire insurance maps, newspaper stories, street directories, and census data.

All that raw data is fleshed out in the memories of those who lived through those times. Some of those stories have been captured in books like They Came Searching by Eddie Faye Gates and Black Wall Street by Hannibal Johnson.

Here are a couple of reminiscences included by Gates in her book that clearly connect the term Black Wall Street to the post-riot, rebuilt Greenwood:

"They just were not going to be kept down. They were determined not to give up. So they rebuilt Greenwood and it was just wonderful. It became known as The Black Wall Street of America."

- Eunice Jackson"The North Tulsa after the riot was even more impressive than before the riot. That is when Greenwood became known as 'The Black Wall Street of America.'"

- Juanita Alexander Lewis Hopkins

But then came the planners:

"Slum clearance," as a cure for Greenwood's ills, had been discussed for years, but in 1967, Tulsa was accepted into the Federal Model Cities program.Model Cities was not just an ordinary urban renewal program. It was intended to be an improvement over the old method of bulldozing depressed neighborhoods. The Federal government provided four dollars for every dollar of local funding, and the plan involved advisory councils of local residents and attempted to address education, economic development, and health care as well as dilapidated buildings.

For all the frills, Model Cities was still primarily an urban removal program: Save the neighborhood by destroying it. Homes and businesses were cleared for the construction of I-244 and US 75 and for assemblage into larger tracts that might attract developers. Displaced blacks moved north, into neighborhoods that had been built in the '50s for working class whites.

Only the determination of a few community leaders saved a cluster of buildings in Deep Greenwood -- but these buildings are isolated from any residential area, cut off from community.

In April 1970, as Tulsa's Model Cities urban renewal program was beginning to demolish homes, Mabel Little, whose new home was burned down in the 1921 attack, told the Tulsa City Commission [from the April 11, 1970, Tulsa Tribune]:

"You destroyed everything we had. I was here in it, and the people are suffering more now than they did then."

Years later, Jobie Holderness reflected on the spiritual damage done by urban renewal:

"Urban renewal not only took away our property, but something else more important -- our black unity, our pride, our sense of achievement and history. We need to regain that. Our youth missed that and that is why they are lost today, that is why they are in 'limbo' now."

Here's my talk on this topic at Ignite Tulsa in 2009:

And here are links to previous BatesLine entries about Greenwood's renaissance:

The Greenwood Gap Theory: My June 2007 Urban Tulsa Weekly column on the popular misconception, abetted by the second destruction due to urban renewal, that Greenwood was not rebuilt after the 1921 massacre.

Notes on the sources documenting Greenwood's post-riot renaissance: My response to OSU-Tulsa history professor J. S. Maloy, who disbelieved my account of the post-massacre revival of Greenwood.

Greenwood 1957: A summary of commercial activity in Greenwood, based on the 1957 Polk street directory of Tulsa.

Greenwood's streetcar: The Sand Springs Railroad (includes photos)

The rise and fall of Greenwood (includes high res 1951 aerial photo of Deep Greenwood)

Tulsa 1957 restaurants: A KML (Google Maps) file locating restaurants listed in the 1957 street and phone directories, including many that lined Greenwood Ave.

Film of Oklahoma's 1920's black communities

Finally, here at a glance are three Sanborn maps from 1915, 1939, and 1962, showing Deep Greenwood over the decades:

Sanborn Map: Deep Greenwood in 1915

Sanborn Map: Deep Greenwood in 1939

Sanborn Map: Deep Greenwood in 1962

FOLLOW-UPS:

- Tate Brady, the Klan, and the attack on Greenwood

- Brenda Terry (Flash Terry's daughter) on Greenwood in the '40s and '50s

- Films of Greenwood post-riot and Oklahoma's African-American communities in the 1920s (the Solomon Sir Jones collection)

- Smithsonian Channel mangles Greenwood history

- Greenwood demolition in 1967 for expressway construction: "There is no Negro business district anymore"

- Greenwood Gap Theory: Tulsa's Green Book places weren't destroyed in 1921

- Segregation by Design: Greenwood and I-244: Adam Paul Susaneck's stark, graphical depiction showing the destruction wrought by the path of I-244 through Greenwood and neighboring districts, and the Guardian article on plans to remove I-244

UPDATE 2020/06/03: Since this article has become a central repository of links to my work on Greenwood, I'm updating the title, which was originally "The 1921 Tulsa Race Riot and the 90 years that followed." I've also changed the first paragraph to be less date-specific. It originally read: "Today is the 90th anniversary of a white mob's attack on Tulsa's African-American district, known as Greenwood after its principal avenue. The attack, which began the evening of May 31, 1921, killed hundreds and left thousands wounded and homeless." I also changed the phrase "over the last 30 years" to "in recent decades."