Greenwood: July 2017 Archives

Relevant to yesterday's post on the Smithsonian Channel documentary that misrepresented the history of Greenwood, Tulsa's historic African-American neighborhood that its residents rebuilt after it was sacked and burned in the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot. The rebuilt neighborhood thrived and prospered for decades, becoming known as Black Wall Street, before urban renewal and expressway construction destroyed it again in the late 1960s. Here is a news story from the time that illustrates the social and financial impact of the decision to route the expressway through the heart of the Deep Greenwood commercial district.

From the Tulsa Library's online "vertical files," this article from the May 4, 1967, Tulsa Tribune, shows a photo of the demolition of the Dreamland Theater to make way for I-244. The story reports on the number of long-time small businesses that are closing down because they can't get financing to reopen somewhere new. Although the library's PDF has OCR text, it is full of mis-scanned words, so I decided to transcribe it here, and correlate it with other contemporaneous sources of information.

An Old Tulsa Street Is Slowly Dying

Greenwood Fades Away Before Advance of ExpresswayBy JOE LOONEY

An old man walked doen the sunny side of Greenwood Avenue and paused to stare at a pile of rubble.

Across the street, Ed Goodwin looked out the window of the offices of the Oklahoma Eagle and shook his head. "That's L. H. Williams," the Negro publisher said. "He comes down here every day. Since he had to sell out, he's just put the money in the savings and loan and lives off the interest . . ."

Ed Goodwin and L. H. Williams grew up with Greenwood Avenue. They remember the early days, when the first buildings were put up in the two blocks north of Archer Street.

They saw the riot of 1921, when many of the buildings burned. They saw the street rebuilt, grow and prosper. They saw, too, as a slum festered.

And now they are watching Greenwood Avenue die.

Its business district will be no more.

THE CROSSTOWN Expressway slices across the 100 block of North Greenwood Avenue, across those very buildings that Goodwin describes as "once a Mecca for the Negro businessman--a showplace."

There still will be a Greenwood Avenue, but it will be a lonely, forgotten lane ducking under the shadows of a big overpass. The Oklahoma Eagle still will be there, but every forecast is that some urban renewal project will push down the buildings that have not already been torn down by the wrecking crews clearing right-of-way for the superhighway.

Williams' son went to college and got a degree in pharmacy. He helped his father in the drug store, later was its manager. Today, he is looking for a job. He can't get financing to build another drug store anywhere.

"Very few of the businessmen here are able to get the financing they need to relocate," Goodwin said. "A Negro just can't do it. So, most of them are just out of business."

IT WAS BECAUSE of financing that Goodwin stayed on the street when [sic] he grew up instead of building a new office in another neighborhood.

His father operated a grocery store in a building across the street--one of those torn down to make room for the expressway.

"He built it in 1915," Goodwin recalled. "and it was destroyed in the 1921 riot. But he rebuilt and there was a grocery store there until 1930. I ran a furniture store there for a while, then put the Eagle office in there in 1936."

There, the Oklahoma Eagle remained until last year.

Goodwin owned an old theater building. It was not in the path of the highway.

"I wanted to put the paper out closer to my house, but they wanted so much money for the property, I decided it would be better to put the money into the building."

In the midst of old buildings, most of them dark, red brick structures dating to the early 1920s, he built a shining modern buff-brick structure. Behind the new building housing the Eagle, in what had been the orchestra pit of the old theater, he put a sunken garden.

OTHER PIECES of history have scattered away. There was the Dreamland Theater. J. W. Williams built it in 1916, then rebuilt it after it burned in the 1921 riot. A Negro Elks lodge moved in years ago, and this was a leading social center for the Negro community.

A rather substantial expressway pillar is slated to plunk down just about where the lobby of the theater was. The Elks managed to find a house 15 blocks up the street and there they moved a few weeks ago.

Otis Isaacs had a shoe shop next door. He rented his space from Alex Spann, who owned many of the buildings on the street. lsaacs had to shift for himself. He found a place 10 blocks away.

Attorney Amos Hall had an office downstairs. and upstairs had provided space for the Negro Masonic Lodge, of which he is Grand Master. Hall and his lodge both moved Into a building five blocks away.

BUT THE WILLLIAMS Drug is not being relocated. Nor has barber Joe Bulloch found a new place to go into business. Dr. A. G. Bacholtz has given up the private practice he carried on for so long on Greenwood Avenue, and is working with the City-County Health Department.

And Alex Spann. the building owner. He had a pool hall. With the money he got for his buildings, he bought another old pool hall a mile up Greenwood.

Hotel owner A. G. Small couldn't build another hotel anywhere. So he decided to retire. Mrs. Joseph W. Miller, whose late husband built a hotel which she operated, also could not rebuild. She, too, has retired.

A couple who operated a cafe gave up their own business and went to work for restaurants in downtown Tulsa. A man who owned a garage was just about able to get his mortgage paid off from the funds from the sale of the building to the highway department. He is not back in business anywhere else.

PAT WHITE was able to move his barbecue stand into a new home on Pine Street. The Christ Temple CME Church moved to Apache and Lewis.

"There is no Negro business district anymore," Goodwin said. Tulsa attached the name of Greenwood to the entire district occupied by Negroes--a name that ironically came from the city of Greenwood, Miss., a pIace hardly considered a Mecca for Negroes.

"They might as well take down all these parking meters," the publisher said. "There's nothing to park here for anymore."

In its heyday, it was a busy street. But the buildings grew old. The Negro population moved into newer neighborhoods. Slowly, integration opened a few doors downtown, on the other side of Archer Street. Places to eat. Go to a movie. To work at good jobs.

RAUCOUS CLUBS and rooming houses sprang up around Greenwood and Archer. Long before the expressway came and brushed the old street away, it was a dying street, like the main street of many an old, small town.

The future? A question mark for some like L. H. Williams Jr. More certain for young Jim Goodwin, who like his father became a lawyer, or for Ed Goodwin Jr., who edits the newspaper his father publishes. For others, they simply are passing from the scene, like the street they knew for half a century.

Right-of-Way for Crosstown ExpresswaySOMETIME, POSSIBLY about four years from now, an elevated eight-lane expressway will cross Greenwood Avenue between Brady and Cameron Streets.

Right-of-way for the project is now being cleared. This Tribune photo looks northwest along the construction path.

Greenwood enters the picture at the upper left, and the buildings in the right background are on Cameron.

The expressway will be about 30 feet above the ground as it crosses Greenwood.

It will carry the designation Interstate 244, and will be part of the Crosstown Expressway which forms the north side of a planned inner dispersal loop around the downtown area.

East of Greenwood, the project is taking nearly all the land between Cameron and Archer Streets as far east as the Texas & Pacific Railway (formerly the Midland valley) tracks.

The expressway will cross Archer Street and both the T&P and Santa Fe railroads east of Hartford Avenue.

West of Greenwood. the right-of-way runs northwesteriy, crossing Cameron before it gets to Frankfort Place.

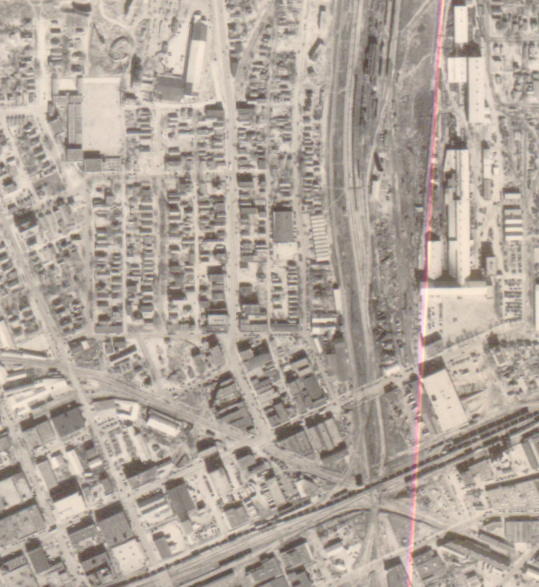

Here is a section of the January 5, 1951, aerial photo showing Deep Greenwood.

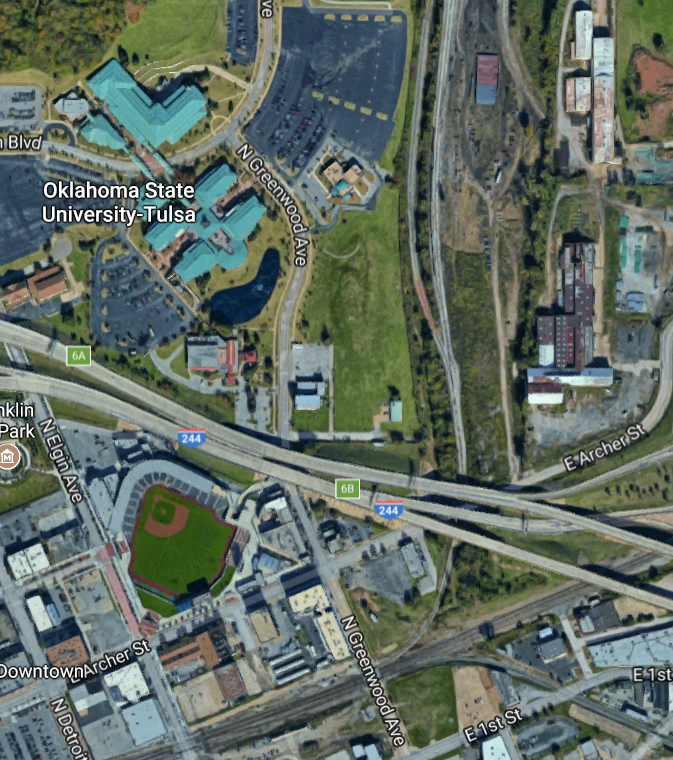

Here is the same area, from the September 10, 1967, USGS aerial photo, taken just four months after the Tribune article. As you can see, the expressway cuts right through the heart of the Black Wall Street business district. Had planners moved the expressway a block further south or perhaps built over the broad Frisco right-of-way, Greenwood would not have lost its commercial heart. Who decided the exact route is a question worth investigating.

Here is the same area as it is today, from Google Maps.

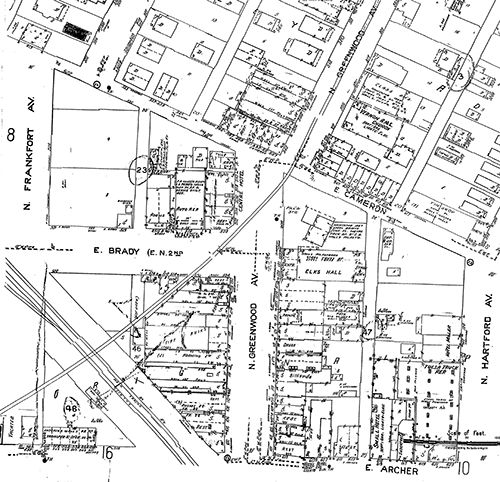

The buff-brick building mentioned in the story is still the home of the Oklahoma Eagle, at 624 E. Archer St., the SW corner of Archer and Hartford. The mention of the theater and orchestra pit on that property sent me looking: Sanborn's 1915 map shows a single-story building labeled "moving pictures" on the south side of Archer just east of the north-south alleyway that split the block; that's west of the "new" Eagle building. 1939 and 1962 maps show a two-story building, about twice as deep as the theater, with rooms on the 2nd floor and two retail spaces on the first floor.

Here is the 1962 Sanborn map covering most of the area described in the article:

On the jump page are lists of businesses, from the 1957 Polk City Directory, on blocks that were affected by demolition. To add context, I've included buildings that were spared (at least spared by the expressway, but those buildings that were demolished for the expressway are shown in bold; italics indicates a business mentioned in the Tribune story. Even though this directory was published a decade before demolition, it's notable that so many businesses were still around 10 years later, persisting until the end. It's also notable that there were so many small, family-owned businesses and so many residences in such a concentrated area.

There was some excitement among Tulsa history buffs when it was learned that the Smithsonian Channel would be showing colorized clips from home movies showing Greenwood, Tulsa's historic African-American district, as it was in the mid-to-late1920s. Instead we have another instance of the erroneous notion I call the "Greenwood Gap Theory" -- the idea that Greenwood was never rebuilt after the riot -- this time being promulgated by one of America's most respected cultural institutions.

The Smithsonian Channel is not available on cable TV in Tulsa, but the program, "America in Color: The 1920s," is available to watch on the Smithsonian Channel website, free of charge. The segment on Greenwood begins about 16 minutes into the program and lasts about 90 seconds.

As American Heritage reported back in September 2006 (noted here on BatesLine a few days later), Oklahoma historian Currie Ballard had acquired 29 cans of film that had been taken by Solomon Sir Jones, a black Baptist preacher, who had been assigned by the National Baptist Convention "to document the glories of Oklahoma's black towns." Yale University has made the Solomon Sir Jones film collection available for viewing online. The stills above are from Film 18; the stills below, from the offices of the Oklahoma Eagle in 1927, are from Film 2.

It's disappointing that Arrow International Media (producers of this Smithsonian series) chose to present images of a prosperous Greenwood (and Muskogee) circa 1925, followed by film of the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot. The order of presentation and the narration leave the viewer with the impression that the riot destroyed the prosperity shown in the Jones films when in fact, the Jones films depict the triumphant resurgence of the Greenwood community after the riot.

It's understandable that a member of the general public, knowing about the 1921 Riot and seeing the area as it is today, might leap to the conclusion that Greenwood was never rebuilt. But the producers of the Smithsonian video had access to all the information they needed to tell the complete story.

Doug Miller of Müllerhaus Legacy, a publishing house in Tulsa, debunks the Smithsonian presentation with precision and passion.

I was initially excited today to see that the Smithsonian Channel was including Greenwood in a new documentary entitled "America in Color." But, upon watching the section that discussed Greenwood and the race riot, I was saddened to see an almost total misrepresentation of the the film footage. I immediately saw significant errors and omissions that, in my opinion, rob Greenwood of its rightful legacy.As you'll read below, the mistakes are many and were so obvious that I can only assume they were made knowingly with the intention of elevating narrative above fact. It's a practice that has become common place in the news media today. Sadly, it has apparently also filtered down to historians. Before supposing that these errors don't really matter, I hope you'll read my entire post. I outline the errors that I think matter very much. And I explain why.

Miller lists and rebuts five egregious errors in the segment: (1) None of the footage shows Greenwood before the riot, as the narration implies. (2) Much of the street footage shown was actually from Muskogee, as Rev. Jones's meticulous title cards clearly indicate. (3) Greenwood's founding is misrepresented. (4) The riot is depicted as an attack motivated by universal white resentment against Greenwood's prosperity; the reality, documented in contemporary news sources, is much more complex.

The fifth error does the greatest cultural damage:

Fifth, and most damning: the film says nothing of Greenwood's rightful legacy. Perhaps I should not single out this film on this point. Most tellings of the Tulsa Race Riot are, in my opinion, guilty of doing the same. I have long been of the opinion that the rebuilding of Greenwood needs to take its rightful place as one of the single most powerful and inspirational stories of Black America's fight to overcome the injustice of segregation and racial inequity. When one fairly considers the breathtaking scope of the destruction, the speed of reconstruction, the opposition to rebuilding (even within the black community), and the defiant independence with which the community achieved all they did, one cannot help but be moved at the level of the soul.Yet, while the story of the riot is advertised far and wide, very few Tulsans and even fewer outsiders know the glorious story of Greenwood's rebuilding. From my own personal interactions, I dare say that most Tulsans believe that Greenwood's history ended in 1921. Many people are shocked to find out that Greenwood reached its economic peak in 1941 and continued to thrive well into the 1960s.

No, the white mob did not win. Greenwood won. And that should be what every Tulsan remembers best about the legacy of Greenwood. It is a story of remarkable victory, not defeat and destruction. To say otherwise is to deny the inconceivable achievement of every African American father and business leader who died protecting their community and their families during that horrific event. And, who chose to defiantly stay in Tulsa to rebuild.

Miller is absolutely right on all points: Most people assume that the Riot is the reason that so little of Greenwood remains (and that the neighborood to the west is vacant except for a few eerie Steps to Nowhere).

Miller is right, too, that the rebuilding of Greenwood is an inspirational story of African-American resiliance, perserverance, and initiative in the face of violent racism that every Tulsan, every American ought to know.

So why is there this preference for the Greenwood Gap theory, the notion that "Greenwood's history ended in 1921"? Why is the rebuilding rarely mentioned in discussions of the Riot?

I have two hypotheses: One speaks to local political concerns and the other deals with national cultural sensitivies.

The local hypothesis is that Tulsa's civic and cultural leaders found it more pleasant to leave people with the incorrect impression that Greenwood was never rebuilt than to face their own culpability in its second destruction. If you remind people that Greenwood was rebuilt, bigger and better than before, according to eyewitness accounts, it raises a question in their minds: Why isn't it here anymore? And the answer to that question raises questions about decisions made, mainly in the late 1960s, by people who were still alive and active in city government and community affairs for decades afterward:

- Who signed off on the decision to run I-244 right through the heart of Deep Greenwood?

- Who decided that the Greenwood and Lansing Avenue commercial districts should be demolished?

- Who decided to demolish the original Booker T. Washington High School, a building that had survived the 1921 Riot?

- Why were the promises of new and better housing, retail, and community facilities never fulfilled?

- Who among African-American community leaders lent their support to these plans?

- How is it that a well-intentioned, progressive program like Model Cities, part of President Johnson's War on Poverty, resulted in the destruction of Black Wall Street?

It's easy to imagine city leaders thinking: Better that Tulsans should blame long-dead city leaders and anonymous rioters for the destruction of Greenwood than to wonder about the judgment of present-day leaders who signed off on its second destruction.

Some day, someone needs to write the history of urban renewal in Tulsa, with a particular focus on the Greenwood District and Model Cities.

But these local factors would not have influenced the writers and producers of the Smithsonian documentary.

This is the most generous spin I can put on it: They couldn't believe that Greenwood was rebuilt so quickly after the riot (or at all), so they assumed that the dates on the films were incorrect and that the scenes of prosperity predated 1921.

My hypothesis regarding Greenwood and national cultural sensitivites is twofold: First, that the story of Greenwood's reconstruction would undermine the left-wing narrative that only government action can right societal wrongs, which are the result of capitalism and individual liberty. This was the gist of OSU-Tulsa Professor J. S. Maloy's objection to my 2007 column about the Greenwood Gap theory, expressed in a letter to Urban Tulsa Weekly: "The free market will always indulge racism, ignorance, fear, and sheer pettiness of spirit in the name of profits. Only a democratic process--public investment constrained by public consultation--can do better." While his letter to UTW is not online, the original version of my rebuttal is here, detailing my sources and inviting him to do his own investigation. Maloy's apparent ideological commitment to the superiority of government action to voluntary action led him to disbelieve documentary evidence to the contrary.

Second, that the reconstruction of Greenwood and the resilience of its people raises uncomfortable questions about present-day American culture. If Tulsa's African-American community could rebuild within a year, despite government-imposed obstacles, despite the resurgent Ku Klux Klan, what was it about the character and social capital of that community that we lack today?

TAKE ACTION: Tulsans concerned about an accurate portrayal of Greenwood's resurgence can contact the Smithsonian Channel and urge them to issue a correction and to edit the narration and sequence to reflect the correct locations and chronology.

We would love to hear your thoughts. Send Smithsonian Channel your suggestions, comments, questions, and concerns to contact@smithsoniannetworks.com or call us at 844-SMITHTV (764-8488).